LAST VIBRATIONS

As long as the many war campaigns of the twelfth century were conducted on a reasonably friendly footing they brought no intolerable hardship to the people who dwelled in the shadow of the castles. But early in the thirteenth century the full disasters of war overtook the land of the troubadours, and poets learned to sing a more doleful tune. Using religious heresy as a pretext for invasion, the north of France launched a ”crusade” against the south that all but eradicated the basis of Provencal civilization. The Albigenses were premature Protestants of a sort, inspired bty Eastern metaphysical doctrines, and their ”heresy” found ready acceptance among the tolerant, poetry-loving nobles of southern France. In 1209 Pope Innocent III proclaimed a military crusade against them, and a vast army of marauders swept down from the north to lay waste to the countryside.

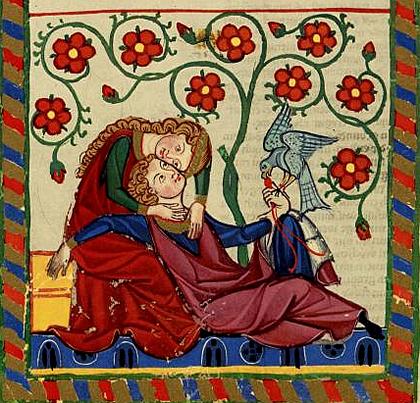

Illumination from a fourteenth-century German manuscript depicts a famous minnesinger, Konrad von Alstetten, lying beneath a flowering tree in the arms of an amorous lady; a flacon perches unconcernedly on his hand.

”Kill Kill! God will know his own”, was the notorious order issued by the Abbot of Citeaux when the French soldiers discovered they could not distinguish between true believers and heretics. Five hundred towns and castles were stormed, sacked and cleansed of heresy by fire. As always the news traveled with the troubadours. One song or ”Sirvente” by Peire Cardenal, ”Churchmen pass for shepherds, but they’re murderers/ King and emperors, dukes, counts, and viscounts, and knights as well used to rule the world;/but now I see churchmen holding sway with their thefts and treachery and their hypocrisy, and heir violence and their preaching.”

Though the crusaders were ultimately withdrawn, Provence was forever annexed to northern France, and the culture of the midi ceased to exist as a separate entity. Troubadour poetry after the fall became stylized and moralistic; the cansos that poets formerly composed for their mistresses were now readdressed to the church or to the virgin. In 1229 the Council of Toulouse established the Inquisition as a regular tribunal, bringing to an end what Ford Madox Ford called ”the last civilized state and creed that Europe was to know.”

''Image: a courtly German knight, Der Schenk von Limpurg,from the early 14th-century Manesse Codex.''

Several unreconstructed troubadors found refuge in Lombardy and in Sicily, where there example prompted Dante Alighieri to try his hand at poetry in the Italian vernacular and ”to put into verse things difficult to think.” The troubadours who remained may have been gifted, but the times were against them. As Guiraut Riquier sang: ” In noble courts no calling is now/less appreciated than the fine art/of poetry, since men prefer/ to see and hear frivolity…” Riquier died about 1294, and with him the living tradition of the troubadours.

What remained of their work are about 2,500 poems preserved in various manuscript collections and some 270 examples of their music, written in a rudimentary notation that provides no more than a melodic outline of each song. So, we will only know half of their achievement, for as Folquet de Marseille says in one of his songs, ”A verse without music is a mill without water.”

Musicologists have done their best to reconstruct the missing rhythms. The limited notation indicates melodic intervals but reveals nothing of rhythm, ornamentation, or accompaniment. Friedrich Gennrich published all the known songs in modern transcriptions but the trouble with his arrangements and those of every other scholar is that they sound dull and musicological. The difficulties seem close to insurmountable to capture the essence. However, the aural tradition runs deep and may be most closely found to resemble the folk songs of Majorca which seems likely to resemble how the troubadours sang their songs; taut irregular rhythms that expand and contract with the inflections of the language and a vocal line ornamented with Moorish arabesques, like smoke rising and curling on a breeze.

Majorcan folk songs have hardly changed since that fateful year of 1229, which marked not only the end of liberty in Provence but also the invasion of Majorca by a force of Catalans under Jaime I of Aragon, who was at the same time lord of Roussillon and Montpellier in southern France. Jaime pushed the Moors out of Majorca and settled his own followers on the island. Their language was first cousin to the Provencal spoken by the troubadours. The peasants in the hinterlands went on singing their traditional songs right into the twentieth century.

Troubadours sprang from ''jongleurs'' who were in the words of Maurice Valency, '' musical vagabonds trudging the roads of the Middle Ages, their stomachs and purses empty, their hearts full of pride.''

It is not an accident that Majorcan peasants refer to their songs as ”vers” just as the early troubadors did, and that they employ some of the same images and rhyme schemes as those that occur in the twelfth century troubadour songs. The question then is whether these folk songs are the root stock on which Bernart de Ventadorn grafted his love songs, or merely the countrified descendants of a once aristocratic art? Which came first, the folk song or the art song? At this point the riddle is probably past solving. But it exists, among the wheat fields and almond orchards, among the furthest outcroppings of a forgotten culture, that you can feel the last vibrations, like the seismic tremors of a far distant earthquake, of the sexual revolution of the Middle Ages.