MANET: DESIRES OF THE PASSING MOMENT

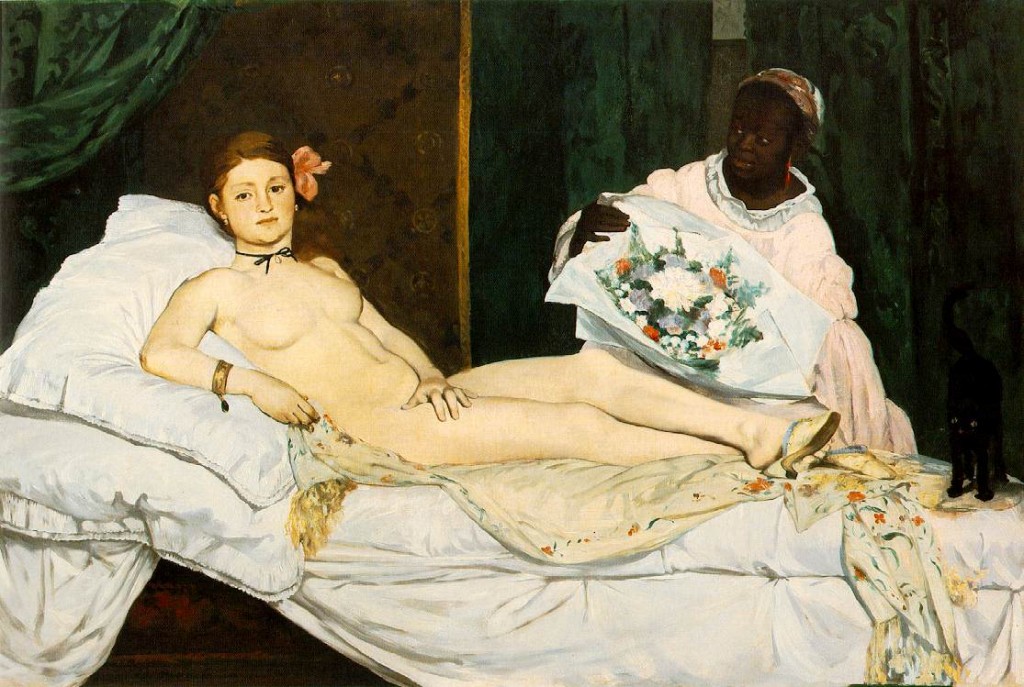

… and beauty of the eternal. Is love pleasure or desire? The Good, the Bad and those eternal constants. Edouard Manet, proved that he was an observer of a world in constant flux. Through the initial reaction to ”Olympia”, idealism is defeated by realism and eternity by impermanence, and the artist gives birth to the visual equivalent of Modernité, noun inspired by Charles Baudelaire and slogan of this era. However, as a result to this overthrow, comes the isolation. ‘I truly wish you were here . . . for insults rain down on me like hail, and I have never before found myself in a situation like this’, Manet writes to Baudelaire on the 4th of May, 1865.

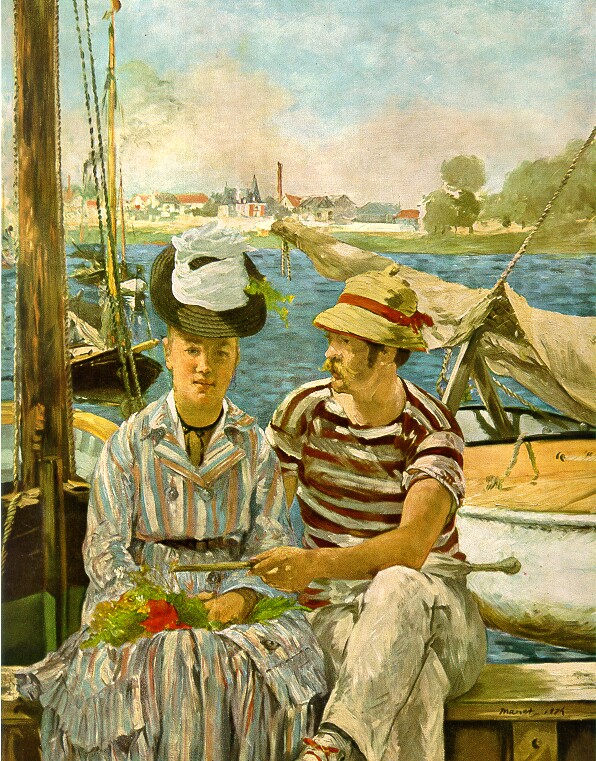

Manet. Boating. " Like Argenteuil it is a ’sketch of manners’, depicting members of society engaged in their favourite pursuit. In his essay, Baudelaire states that for this ‘the technical means which is the most expeditious … will obviously be the best’.13 An awareness of this notion is evident in this, and other, Manet paintings. It is characterised by fast and efficient brushstrokes - suggesting form and modelling through the rapid, often minimal, application of paint. Manet’s expeditious style is a direct reaction to the fleeting nature of modern life; his technique is necessary for his subject: ‘in trivial life, in the daily metamorphosis of external things, there is a rapidity of movement which calls for an equal speed of execution from the artist.’14 At the same time that Manet allocates a large degree of his composition to the expression of the dynamism of modern life he does not neglect that other, eternal element, which Baudelaire spoke of: the static pose of the man (who this time is emphasised with his centrality, and the fact that the woman’s face is painted in profile) is dignified and statuesque. It suggests the underlying presence of that immutable element. Manet, then, is ‘the painter of the passing moment and of all the suggestions of eternity that it contains.’

The painting is led by Manet to the two dimension space, to the equation of form and tool, or stroke. The art critic Clement Greenberg, considered these elements as the principle characteristics of modern art. Attendant to the sentimental detachment is the anaesthetization of the item which, therefore, becomes an excuse for the painting action to come. Olympia’s body is nothing more than a colour spot in the composition of Manet’s work. The human loses his human hypostasis and turns to a visual message. Painting doesn’t mean anymore to describe and imitate, but rather express its own form. The school of “Art for art” sets in with Manet.

The enormous variety of his art and his undogmatic approach to it makes the term artist seem less fitting for him than the title Baudelaire gives to Constantin Guys: “Man of the world” , “a man of the whole world, a man who understands the world and the mysterious and lawful reasons for all its uses”. This concept helps us understand Manet’s approach to painting: he does not turn to modern life merely in search of subjects; instead he resorts to painting in a frantic attempt to preserve the quintessential aspects of modernity before they pass into memory, to keep a record of the harmonious relationship between life and art, eternal and ephemeral, vital and insignificant.

Manet seeks to understand every aspect of the modernity surrounding him – both elegant and savage, the enlightened and the profane – by carefully observing them and conducting these experiments in paint. And yet, he is not a mere illustrator: “few men are gifted with the capacity of seeing; there are fewer still who possess the power of expression” ( Baudelaire ), and therefore the final conclusion is that Manet was indeed “The Painter of Modern Life”.

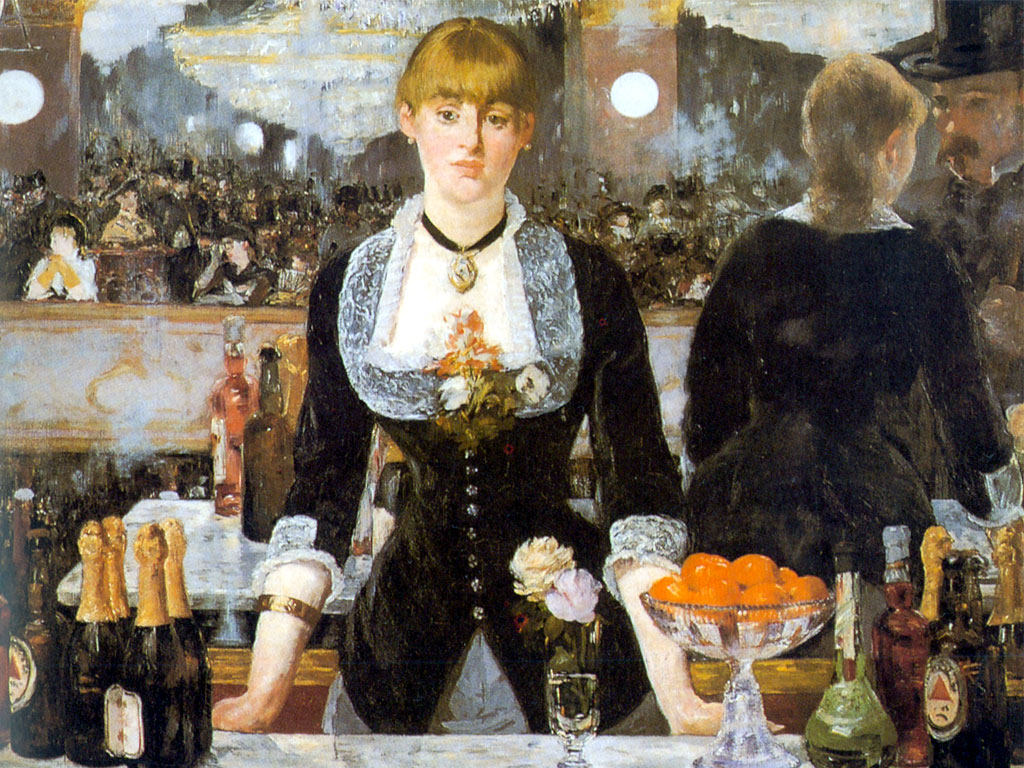

Manet. Folies Bergeres."...each of these paintings is, as Baudelaire said, ‘a sketch of manners’. To give the fashions, the vogue pastimes, the various intimations of modernity precedence, Manet subordinates every aspect of his compostions to them, conveying them with an eloquence and a passion that transcend any lack of clarity or order his compostions may contain. The backgrounds to these paintings all have a distinctly artificial tone: the mirror in Folies-Bergère; the ill-proportioned stage-set of Déjeuner. In Argenteuil the boats and the far bank have been assembled in a jarring, constructed manner. Boating sees the omission of the horizon, an unnatural suppression of the scene. These effects give the paintings a charade-like quality, a pictorial illusionism which Baudelaire saw as characteristic of modern Parisian life."

“At the centre of Baudelaire’s argument is a debate about the inter-relation of two concepts, beauty and modernity. Beauty, he insists, has a dual nature, two elements have been integrated to compose the complete concept: an ‘eternal, invariable’ element and a ‘relative, circumstantial’ one. He attests that the first is extremely difficult to define, while the second is frequently ‘the age, its fashions, its morals, its emotions’. He relates this theory of beauty to the practice of art by classifying the ‘ephemeral’, ‘fugitive’ contingent of beauty as ‘Modernity’, ‘the half of art whose other half is the eternal, and the immutable’. Thus, all artists are obliged by necessity to include something of both elements in their works, because ‘without this second element . . . the first element would be beyond our powers of digestion or appreciation, neither adapted nor suitable to human nature’.”

An with Edouard Manet there is always the beautiful paint. As a pure painter- which is to say by the contemporary yardstick that eliminates an artist’s pictorial subject matter and judges him by what is left- as a pure painter, Manet anticipated the kind of contemporary abstract art, where paint both as a physical substance and as color is manipulated for the pure delectation it affords in itself . Manet’s withdrawal from storytelling , from idealized statement, from psychological investigation, from the pictorial clues that tempt he observer to read rather than to see it as a work of art with an independent existence: these withdrawals are prophetic of a time when the withdrawal has become complete.

The act of painting itself may have been for Manet even more important than the subject that served him as a framework for this act, which explains why he frequently allowed himself the convenience of borrowing the general scheme of a painting from Titian, as he did in “Olympia” , from Goya, as he did in “The Balcony” , or from raphael as he did for the grouping of the three foreground figures in “Le Dejeuner”. He borrowed frameworkss only; it was the doing of the painting that counted.

Manet. Olympia. 1863 "In this famous painting, Manet showed a different aspect of realism from that envisaged by Courbet, his intention being to translate an Old Master theme, the reclining nude of Giorgione and Titian, into contemporary terms. It is possible also to find a strong reminiscence of the classicism of Ingres in the beautiful precision with which the figure is drawn, though if he taught to placate public and critical opinion by these references to tradition, the storm of anger the work provoked at the Salon of 1865 was sufficient disillusionment."

“The impressionist palette included many recently developed synthetic pigments. Manet is thus ingraining his pictures with signs of modernity in the paint itself, as well as the subject and style. The ephemeral brushstrokes observed in several places, particularly the man’s face, merely suggest form rather than depict it. In other passages colour has been lavishly applied in dense, rich bands. This marks the painting with Manet’s own inimitable style, distinct from his impressionist contemporaries, who tended to favour an egalitarian attention to each aspect of the scene. In Argenteuil the device is effective in draining the man of identity, leaving him present only as a force, a phenomenon of the environment, something to contend with. He is a stereotype, man in general, suggestive of his station and affiliation in the same way that the crude brushstrokes are suggestive of his features. Again, this figure seems to be propositioning or demanding something of the female, with a similar gesture to his counterpart in Déjeuner. The woman to whom he directs his attention is clearly disinterested and does not return his glance.” ( Michael Johnson )

Johnson:Her features have been clearly defined and she is thus our focal point as well as his - an effect that is also achieved through the bold juxtaposition of black and white in her hat. An inordinate degree of attention seems to have gone into this hat; its elaborate construction has been assiduously transcribed as if being preserved because Manet was pained by the fleetingness of fashions and wished to record his fascination with them, perhaps having in mind Baudelaire’s insitence that artists do not neglect them.

It has seemed logical to contemporary painters to eliminate the pictorial framework altogether and to let the act of painting exist for itself. “Nothing is important to me except what is happening on the canvas as I work,” they have said. Manet, in a still life of inconsequential objects or even in the secondary details of a major painting, comes within a hairsbreadth of this contemporary conclusion. But his greatness is not in his prophecy; it is in the completeness with which he fused the delight of painting with a vivid record of his world.

Michel Foucault’s discussion of Manet was based on three elements: the materiality of the canvas, the lighting, and the positioning of the spectator. By means of his inversion of traditional painterly tactics, the tactics of ideality and illusion, Manet will be the first painter to submit the represented spectacle to the exterior demands of objecthood, as the ideal enters the jurisdiction of the real. This “rupture” is itself the appearance of a new object: “This invention of the tableau-objet, this reinsertion of the materiality of the canvas into that which is represented, it is that which I believe to be at the heart of the grand modification brought on by Manet…”( Foucault ) It is this heterogeneous object, the tableau-objet that gives Manet relevance for Foucault beyond impressionism; in fact, Foucault will credit Manet and the tableau-objet with making possible all painting of the twentieth century although we might question how far this influence extends beyond Post-Painterly Abstraction.

Manet, Edouard 1832-1883. "The Port of Boulogne in Moonlight", 1869. Oil on canvas, 81 x 101cm. (Photo Erich Lessing)

ADDENDUM:

Furthermore, this intrusion of the real, objective components of the canvas into the space of representation is complimented by Manet’s use of a real, external lighting affecting the picture plane from the outside. In fact, Foucault will insist that as the source of illumination loses its divine, ideal source that worked from inside the picture plane, it relocates itself in a new agent outside the painting: the spectator. In speaking of Manet’s Olympia, Foucault says, “A lighting that comes from the front, a lighting that comes from the space that is found in front of the canvas, that’s to say the lighting, the illuminating source that is indicated, that is supposed by this lighting of the woman, this illuminating source, where is it if not precisely where we are?” Thus, it is not simply an external lighting, but rather an external lighting that is grounded in the gaze of the spectator, since “our gaze and the lighting make but one and the same thing.”

Finally, there is the inversion of the spectator’s placement in relation to the canvas. Rather than using the lines of perspective to anchor the spectator immediately in front of the painting, thus preventing the spectator from exploring the material dimensions of the canvas, Manet will use representation to shift the spectator, restoring a certain freedom of motion. This is most conspicuous in Manet’s Un bar aux Folies-Bergère, which serves as the capstone of Foucault’s thesis. Foucault shows how the lines of perspective in this painting offer us three systems of incompatibility that result in the displacement of the spectator—a spectator in motion.

…”In his essay, Baudelaire expounds his notion of life as harmonious, of everything combining ‘to form a completely viable whole.’10 In this view every aspect of life has relevance, and an artist cannot, therefore, afford to pronounce any of them as unworthy as subjects and ignore them, since even ‘the savagery that lurks in the midst of civilisation’11 is part of modernity and its heroic aspects. Manet’s view of modernity was based on Baudelaire’s, and on Baron Hausmann’s destruction and rebuilding of Paris, which had the effect of raising the stones of the city to reveal the lives of the despondent populace beneath. Accordingly, the two figures in Manet’s painting have been drawn from these lowlier stations in life, or if the models were part of his circle and polite society then they have been treated in such a way as to emphasise whatever signs of coarseness their natures may possess. The prominence of the man’s rugged forearm alludes to a lack of elegance and refinement – he is to be associated with labourers and people of restricted means. Yet the painting lacks snobbery, for Manet has allowed the reddish coarseness of their complexions, suggestive of rustic people, to give them an unbridled vitality, an air of unselfconscious, simple acceptance of themselves and their place in society.”