THE DODGY MASTER: PSST… ITS EROTIC ABSOLUTISM

“Besides foreshadowing Warhol, Rubens amounted to the Walt Disney of his day—a hardworking industrialist of standardized pleasures. He not only ran his studio as a virtual assembly line; he oversaw the mass production of prints, based on his paintings, and a luxury line in tapestries, for which he provided cartoons. Given the magnificence of his success, there’s little wonder that he lacked the shadier, more refractory genius of a Caravaggio, a Rembrandt, or a Velázquez. He was too happy. There is a sublimity about Rubens, after all. It just doesn’t quite belong to him, but to a world and a time that made such art, and such a life, possible. ” ( Peter Schjeldahl, The New Yorker )

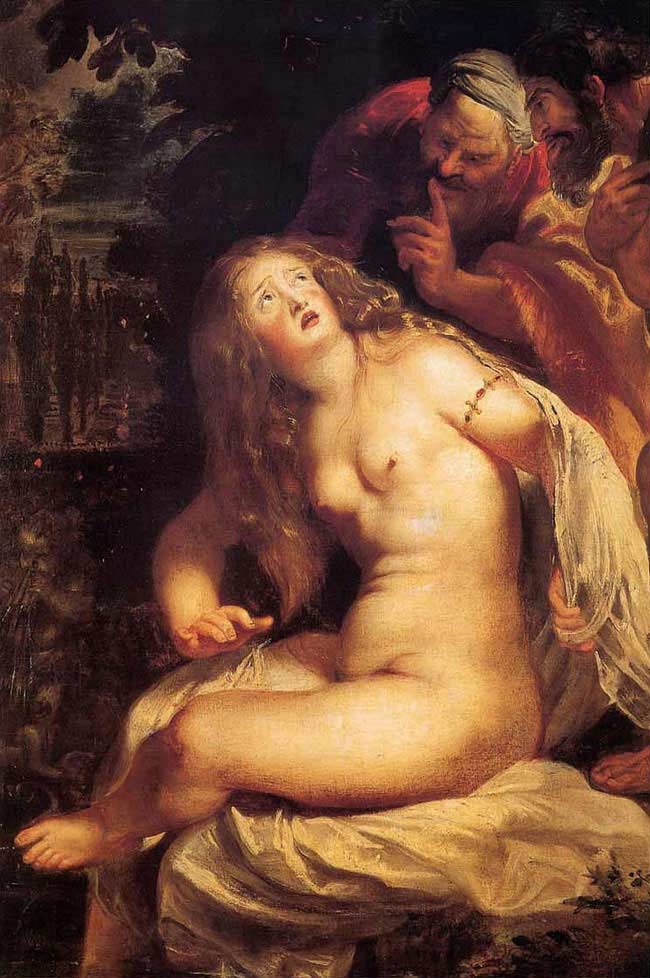

"This is the first painting Rubens makes on the subject of Susanna. The elders spy on Susanna taking a bath, and are taken with her charms. They approach her. When she rejects their approaches, they accuse her of adultery. Only by Daniel’s intervention is her death by stoning prevented."

The artist was blessed with rare gifts of organization and a sense for realism and idealism; an idealism that responded to a reactionary theology in which he seemed to act as the well mannered and civilized poster boy or company man; whether wittingly or unwittingly his workshop was a printing press. Rubens’s creative, inventive response to conservative theology and to classical values validated the vast pictorial cycles demanded by his patrons. These filled Antwerp’s new Jesuit church and Charles I’s new banqueting hall ceiling at Whitehall.

Though there is narrative and some intent to be ambiguous in his work, there is a deep conformity towards repression of women and general principles of subjugation.Exactly those themes that catalyzed the Protestant Reformation. Daughter of Leucippus is a generic rape scene, its meaning is perspicuous; that of a victory monument to Catholic, particularly Papal success in subjugating the citizens and subject territories within its reach and grasp of tribute. It is in the tradition of virile heros holding aloft part of a woman’s body as evidence of his capacity to dispossess and incapacitate his enemies; works that play upon the thematics of sexual prowess and disempowerment as a way of establishing the hero/ruler’s capacity in facing down opposition through force.

This of course, was central to Machiavelli’s delineation of the ideal prince and is a recurrent theme in subsequent Florentine political rhetoric. The gendered signification of the word virtù in particular, meaning, literally, manliness, underlies the sexual innuendo in Machiavelli’s endorsement of princely violence. Machiavelli urges the Prince to use force in contending with adverse circumstances:

“Fortune is a woman and if you wish to keep her under it is necessary to beat and ill use her; and it is seen she allows herself to be mastered by the adventurous rather than by those who go to work more coldly. She is, therefore, always woman-like, a lover of young men, because they are less cautious, more violent, and with more audacity to command her….”

The convergence of the sexual and political meanings in the concepts of force and virtù help clarify why this is represented in artistic theory and experience which seemed to find in Rubens’s work, the most candy covered incarnation of the theme; nonetheless, a fitting embodiment of those values that serve as a daunting public affirmation of earlier Medicean princely prowess.

"Once this refiguration of the prince's relation to his subjects is understood, it becomes readily apparent why, in 1583..., Francesco de' Medici, would have found it appropriate to install Giovanni da Bologna's so-called Rape of a Sabine in the Loggia dei Lanzi on Florence's Piazza della Signoria."

However, it’s hard to think of a painterly career more tightly entwined with the great events of his time, as well as with the classical pedigree of his craft. And many of those events go straight to the heart of his “making”. Rubens, after all, first became an artist in Antwerp – a city in which the legitimacy or illegitimacy of sacred image-making had driven men to violence. Nine years before Rubens was born, Calvinist iconoclasts had smashed statues, ripped paintings from the walls of the cathedral. There was a Catholic restoration, but before Rubens was apprenticed there had been another return of Protestant whitewash before it was finally and permanently restored to the Catholic Counter-Reformation. So the intense fervour of Rubens’ religious painting is not just art but spiritual weaponry. And his early career is as much a journey through a war zone as a prolonged exercise in the absorption of classicism.

Cellini. Perseus. "... main view of the the group from the front does yield a more or less coherent view of the bodies of both men. It is the woman's body that we see only as a fractional part, which lacks integrity and has become fetishlike. The fetishistic display of the Sabine woman's body effectively complements the display of the head of Medusa in Cellini's Perseus --the sculpture with which Giovanni de Bologna's group was paired in the Loggia dei Lanzi."

…The pleasures of sexual violence had long been championed in Ovid’s Art of Loving, where indeed this particular rape– by the Dioscuri of the sisters Pheobe and Hilaira– was cited as an example of how a lover might conquer the object of his desire by using force:

Though she give them not, yet take the kisses she does not give. Perhaps she will struggle at first and cry, “You villain!” Yet she will wish to be beaten in the struggle….He who has taken kisses, if he take not the rest beside, will deserve to lose even what was granted…. You may use force; women like you to use it….She whom a sudden assault has taken by storm is pleased….But she who, when she might have been compelled, departs untouched…will yet be sad. Phoebe suffered violence, violence was used against her sister: each ravisher found favour with the one he ravished.

"... painted by Rubens from 1609-12. The painting was looted from Germany by a Russian soldier during WWII, and has been exhibited in St. Petersburg's The Hermitage and Moscow's Pushkin Museum. The history of the painting and Germany's attempts to have it returned are covered by The Guardian, Deutsche Welle, and Passport Moscow."

“In applying this passage from Ovid to Rubens’s painting, one art historian draws the conclusion that Rubens is celebrating the triumph of natural impulse over conventional inhibition: “The battle of the sexes is a necessity of nature. With Rubens it is a primal impulse of life, a fight for unification…..In being raped Pheobe discovers her destiny as a woman. Her rape reveals and enhances her nature.” In claiming something like a truth value for Rubens’s celebratory depiction of this rape, this scholar mystifies it in terms of a misguided notion of what is natural in human sexuality. My point is that we must consider Rubens’s painting not as a revelation of primal human nature but as a phenomenon of sixteenth- and seventeenth- century European culture. In particular we may view Rubens’s painting as issuing from a tradition that emerged among princely patrons at the time, of incorporating large-scale mythological rape scenes into their palace decorations. With fundamental shifts in political thinking and experience in early sixteenth-century Europe, princes came to appreciate the particular luster rape scenes could give to their own claims to absolute sovereignty….”

"Romulus and Remus were the twin sons of the Vestal Virgin Rhea Silvia, who was seduced by the god Mars. The upper picture above from 1616/7 showing Mars and Rhea Silvia is by Rubens, and is now in Vienna's Liechtenstein Museum."

Exceptional stamina and vitality, allied with an enormous capacity for concentration and for organizing, enabled him to make the most of his crowded working day. He was interested in everything; he appears to have enjoyed everything; and in his voluminous correspondence with a network of humanist friends, he moves easily from discussion of public events to the details of his latest commission and on to a learned discourse of some recently discovered Roman cameo, commenting on each subject in turn with shrewdness, elegance, and a remarkable generosity of spirit.

" Rubens's Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus confronts its viewers with an interpretative dilemna. Painted about 1615 to 1618, the life-size composition illustrates the story recounted by Theocritus and Ovid of how the twin brothers Castor and Pollux (called the Dioscuri) forcibly abducted and later married the daughters of King Leucippus. Rubens's depiction of the abduction is marked by some striking ambiguities: an equivocation between violence and solicitude in the demeanor of the brothers, and an equivocation between resistance and gratification in the response of the sisters. The spirited ebullience and sensual appeal of the group work to override our darker reflections about the coercive nature of the abduction. For these reasons many viewers have wanted to discount the predatory violence of the brothers' act and to interpret the painting in a benign spirit, perhaps as a Neoplatonic allegory of the progress of the soul toward heaven, or as an allegory of marriage. Although I agree that a reference to marriage may be at play here, I also believe that any interpretation of the painting is inadequate that does not attempt to come to terms with it as a celebratory depiction of sexual violence and the forcible subjugation of women by men...."

Behind this extraordinarily versatile performance lay a profound domestic stability. It was tragically interrupted by the death of his wife Isabella in 1626 but renewed in the last decade of his life by his marriage to the entrancing Helena Fourment, who was to bear him five children in ten years. The combination of domestic felicity and international lioninzing could easily have gone to the head of a lesser man, but Rubens, while always conscious of his own worth, somehow preserved his modesty and his sense of proportion.

The truce between Spain and the United Provinces expired in 1621. War returned to the Spanish Netherlands, and, as the year passed, merged into that wider conflict between Protestant and Catholic in the Thirty Years’ War. The misery and devastation of war were a source of anguish to Rubens, who was, in his own words, ” by nature and inclination a peaceful man”. “For my own part, ” he wrote in 1627, “I should like the whole world to be in peace , that we might live in a golden age instead of an age of iron.”

But as the reluctant dweller in the age of iron, Rubens could not evade the rigors it inevitably imposed. During the 1620′s Archduchess Isabella, together with Ambroglio di Spinola, the Genoese commander in chief of the Spanish army of the Netherlands, did everything possible to extricate the southern provinces from a war that threatened to engulf them in ruin. Tied to madrid, which was heavily committed to the international conflict, the government of Brussels had little opportunity for independent manouvring. But it could indulge in a little diplomatic probing on its own, hoping desperately that some rapprochement between Spain and England might bring peace closer. For this delicate diplomatic work, the archduchess needed a confidential agent whom she fully trusted and whose movements would not arouse suspicion. What better choice than Rubens, who had an entree to all the courts of Europe and who could pursue a quiet diplomacy under the convenient cover of his legitimate artistic activities?

"Art began with fat people. The Venus of Willendorf carved in limestone is 24,000 years ago. Among painters, Rubens stands out, which is where the complimentary adjective, Rubenesque, came from, although it doesn't apply to his men. His fat women are voluptuous, while their fat male companions are dim or funny in a Falstaffian vein."

aaSo it was that Rubens started his travels again. In Paris in 1625, he had met that great patron the Duke of Buckingham, the favorite of Charles I of England; in 1626 he had successfully negotiated with Balthasar Gerbier, Buckingham’s agent, for the duke’s purchase of his collection of Roman antiquities. And now, in 1627, on a tour of Holland he combined art with diplomacy, meeting with Gerbier and the English ambassador to the Hague. Soon afterward he was summoned to Spain to report on his activities.

Twenty-five years had passed since his last visit to Spain, and in the intervening period much had changed. The bland duke of Lerma, the favorite of Philip III, had been replaced by the dynamic and aggressive Olivares, the favorite of the new king, Philip IV. Rubens’s long conversations with Olivares still left him time to paint the king and the royal family and form a close realtionship with Diego Velasquez, a promising new court painter. It was not the least of Rubens’s achievements that he was able to introduce Velasquez, at a critical moment in his career, to the latest developments in European painting.

The Arrival of Marie de Medicis at Marseilles. 1623-25. Married by proxy, Marie de Medicis, having sailed to france to meet her bridegroom, Henry IV,encounters joyful committee of gods,goddesses, and sea crarures who welcome her to port at Marseilles. The mermaids, their abundant forms twisting and turing with super-human energy, virtually soar out of the sea toward the future queen.

After eight months in Spain he returned to Brussels by way of France. After allowing himself just enough time to have a look at his Marie de Medicis cycle, now magnificently installed in the Luxembourg Palace. The in 1629, he was off again across the English Channel to the court of Charles I. England came as a surprise to him. For a country so remote from Italy, it proved remarkable civilized, and Rubens found himself in the court presided over by a monarch of exquisite aesthetic sensibilities. Rubens, with his tact, his refinement, and his deep knowledge of the arts, cut an appealing figure. Before he left he collected a Cambridge doctorate, a knighthood, and a challenging artistic commission: the decorating of the ceiling of Inigo Jone’s magnificent Banqueting House in Whitehall with a series of paintings on a theme hardly less equivocal than that of the life of Marie de Medicis: theblessings of the reign of the late James I.

The Anglo-Spanish peace of 1630 was a tribute to the tact and discretion with which Rubens had performed his missions, but it also marked the culmination and virtual conclusion of his diplomatic career. In 1633, Archduchess Isabella died, and her successor, the Cardinal Infant Don Fernando, the brother of Philip IV, had less need of his services. Rubens took refuge in a country manor house, the Chateau de Steen, and in relative retirement he devoted many hours to exploring and painting the beauties of the Flemish landscape. Although his right hand became arthritic, his versatility and creativity remained ti the end.

The Feast of Venus. 1630-1640. Bouncing cupids are everywhere, even in the trees, in this orgiastic celebration of love, perhaps inspired by Helena Fourment. Their arms intertwined, the nymphs and satyrs at right dance across a garden of love in a feverish pas de quatre, exuding a warmth and softness that are nearly palatable.

“…there are peculiar exhilarations to be found in Rubens that are reproduced nowhere else in baroque art (sorry, van Dyck): the strenuous manipulation of sensation, even profound emotion, through purely pictorial muscle; incomparable draughtsmanship; eye-popping colour. Not for Rubens the darkling palette and the stripped-down casting of Caravaggio (though he took much else from the master whose scandalously naturalistic Death of the Virgin he tried to buy for the Duke of Mantua), nor the introspective psycho-probes of Rembrandt. Rubens is all about meaty animal energy and high-voltage design, the play of what one 17th-century biographer called his furia del pennello – the fury of the brush.

But Rubens’ surging line was never simply a virtuoso flourish. It was always put at the service of the controlled orchestration of bodies in motion. And as a colourist, no one since Titian and Giorgione came close. Whether he was confecting the most delicate flesh tones or throwing screaming vermilion at the canvas, it was with an eye to modelling forms rather than just filling them, thus making the ancient and tedious battle between disegno and colore moot.” ( Simon Schama )

Ultimately, who was Rubens? He never tells. He seems to be best when he is effectively no one, just an attentive eye. The rest is ravishment, with something dodgy in it:

“My keen enjoyment of a sheet of seventeen studies of dancing peasants for a relatively late painting, “Village Wedding” (1635-38), is vitiated by a sense that Rubens was trying not only to emulate his great predecessor Pieter Bruegel the Elder but to outdo him. (The painting, which hangs in the Louvre, is delightful enough, but vulgar in a way that’s endemic to big-budget remakes of classic films.) As for Rubens’s scrumptious portrait drawings—and even the special case of a staggeringly beautiful study for a saint’s head, “Young Woman Looking Down” (1628)—there is always something arch about them. Their charm, not allowed to speak for itself, must be augmented with enlarged eyes and rosy, translucent, perfect skin.”