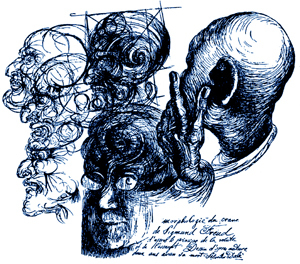

Madness, love and mysticism. Perhaps everything you always wanted to know about Dali, Freud, Psychoanalysis and Pictorial Surrealism. Salvador Dali was immersed in the conquest of the irrational, infinite and likely futile search for the unconscious and its meaning. His contribution to surrealism is linked to the framework of Freudian psychoanalysis through Dali’s unique and sometimes unsettling pictorial symbolism and narrative language. An obsession with the representation of the fourth dimension within a two dimensional painting.

Surrealism, which is credited to Andre Breton, was a style of painting, sculpture and literature that grew out of a fusion between art and psychoanalysis. Call it a marriage of convenience consummated after WWI. Its predecessor was the Dada movement which involved a systematization of confusion. Intentional ruptures and disturbances to linearity through juxtapositions of context, form and style, that took shape as free association; indeed one of the Zurich and later Berlin Dada’s founders, Richard Huelsenbeck, became a Jungian Psychoanalysist in New York after fleeing from Germany. Certainly, Breton was not above opportunism, and he theorized and appropriated Freud in a completely different manner. Breton wrote the Surrealist Manifesto to describe how he wanted to combine the conscious and subconscious into a new ” absolute reality”

”Surrealism emerged in the aftermath of WWI. Along with the Dadaism that prepared the way for it, it was a rejection of bourgeois values, especially the rationalism that supposedly accounted for the wholesale destruction of life and property just concluded. It attacked the pretensions of high art, while retaining many of the painterly flourishes of earlier generations. When Marcel Duchamp painted a moustache on the Mona Lisa in the Dadaist “L.H.O.O.Q” in 1919, he captured the spirit of this movement. In many ways, it was to the radicalization of the 1920s as people like Abby Hoffman and the Fugs were to the 1960s radicalization.”…Freud’s “insights” informed nearly everything that both the writers and painters produced. It is important to understand that surrealism did not take a literal-minded and clinical approach to Freud’s theories. For the most part, it did not look at psychoanalysis as a means to achieving mental health, something largely unattainable in bourgeois society in any case. Instead, they saw it as a way of tapping into the deep psychic reservoirs that can produce memorable art. More to the point, mental illness–and hysteria in particular–was a normal response to the insanity of capitalist society. Their notions on this relationship anticipated not only R.D. Laing but the postmodernism of Deleuze-Guattari and Lacan.”

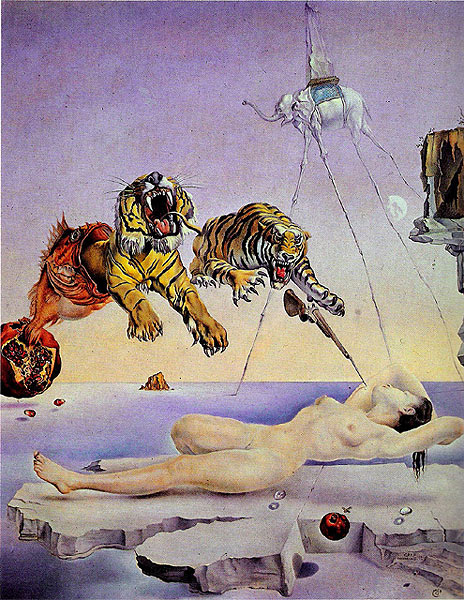

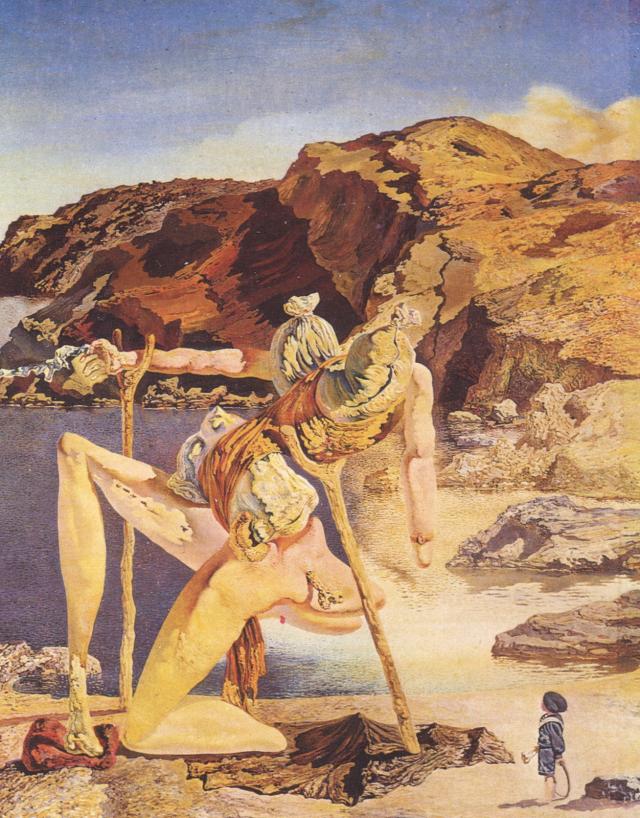

With Freud, the status of dreams changed. They were still seen as sources of knowledge, but this time they were more about one’s past than future, and the messages delivered were sometimes difficult to absorb. They were often carnal and murderous, bringing to light aspects of ourselves that were obscure. They showed humans not as autonomous agents but as divided, split between what they wished for at a conscious level and the echoes of their unconscious desire.What Wittgenstein would refer to as Rules and Private Language. Surrealists like Dali explored not the rational goals of human activity but what blocks these pursuits, the impediments that give human life its deep variations . By taking these dark threads and magnifying them, they are faithful to the mysterious world of desires and defences Freud mapped out in The Interpretation of Dreams.

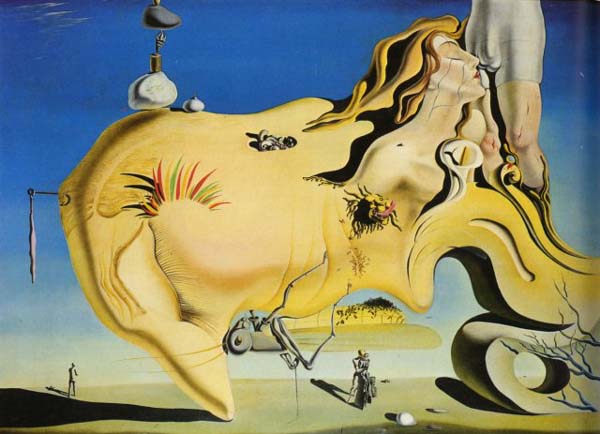

The interface between Freudian dream theory and literary and artistic production is not complex. What counts is less what is said than how it is said. It has nothing to do with content: it is not about sex or the Oedipus complex or murderous wishes. If these are universals of human life, what matters is how they are articulated. And, as Freud showed, the key lies in censorship.The surrealists provide the best example. Surrealists were a group of writers and artists who, for the most part, were keen readers of Freud and who had paid careful attention to his theory of dreams. They knew about the sexual drives, about Oedipal desires, about the castration complex etc.

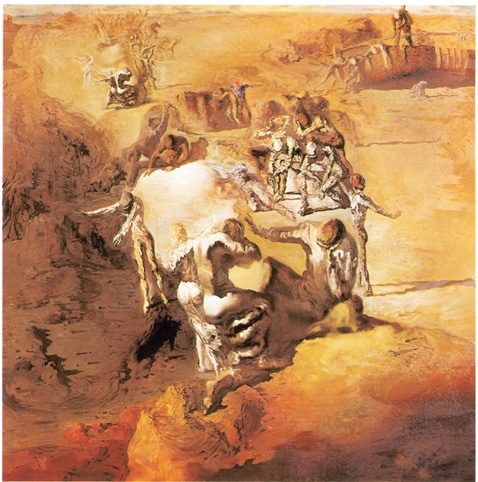

The unconscious desires Freud brought to light are, in fact, no more present than in any other art movement. But what we do find are the mechanisms of the dreamwork, the ways desire slips through the nets of censorship. When a desire cannot be represented consciously, Freud showed, it will take on the form of some absurdity. Two objects that could never be juxtaposed in reality become so in the dream: an artichoke and a human head, a fish and a bicycle. They are condensed into one, as a way of disguising desire.These juxtapositions could not happen in real life, just as in Dalí’s work we continually see things next to each other that couldn’t be so empirically: bodily fragments next to landscapes and rocks, strange creatures part-human part-animal, machines with flesh, living bodies and objects improbably enlarged and reduced in scale. Psychoanalysis is not a playful as art can be, with its mechanisms of binding and distortion.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Great post mate! Where

Agnus, thanks for reading.

I think very much a great attention to so insignificant theme in art, for me, not interesting to consider sexual desire (creativity Dali).

I would imagine it has a role, but don’t know enough about the relationship to creativity to offer any comment.

Dave