Andre Gide, a minor novelist, once called the “Comedie Humaine” of Balzac a great fresco crumbling to pieces a little more all the time. Given that he is not entirely wrong, it could be extrapolated today that the novel as art form is further along the path to extinction and our literary edifices is supported by far fewer readers than in Dicken’s era.

A threatened species which outside of obligatory academic necessity, is not particularly capable of stirring the imagination of contemporary youth. An Orwellian nightmare where in the future all literature becomes incomprehensible under the merciless sway of its own inventiveness, a future where people will swallow pills that approximate a sexual experience in order to convince themselves they are still individuals.A victory of sensation and feeling over reason. When Dickens died in 1870, the press referred to him as “The intimate of every household”. Much water has washed and flowed under London Bridge since. Are there still any vestiges and lasting virtues of Dickens and his great English Comedie Humaine that have endured?

Unfinished painting by Robert William Buss shows Dickens in his study at his country home in Kent surrounded by his literary offspring. Little Knell, his favorite is perched on his knee; Paul Dombey appears just above his right hand, and Sam Weller in the upper left corner. Buss copied some of the etchings of Dicken's illustrator, Hablot K. Browne, known as "Phiz".

Speaking as David Copperfield, Dickens allows his hero to reveal much of the character of his creator; “Whatever I have tried to do in life, I have tried with all my heart to do well… whatever I have devoted myself to completely… in great aims and in small, I have always been thoroughly in earnest. I have never believed it possible that any natural or improved ability can claim immunity from the companionship of the steady, plain, hard working qualities, and hope to gain its end”. From Dicken’s own poverty filled childhood, his experiences were forever imprinted by a near photographic memory which in the words of David Copperfield, looked at nothing but saw everything.

No doubt Dickens himself would have been shocked if he had been called an anarchist, but fundamentally that is what he was.As a parliamentary reporter for an evening paper, he termed the institution of elective democracy, ” the great dust heap of Westminster”. As a court reporter, he was contemptuous of the law, partcularly the machinery of justice; one feels the zest with which he put into the mouth of Bumble the immortal remark, “If the law supposes that, the law is an ass, an idiot”. Dickens was an individualist who never lost an opportunity to mock the legislature and likely would have been exasperated by a tenth of the socialism in the British welfare state apparatus of today.

It is no exaggeration to assert that the sum total of comic figures created by novelists writing in English before Charles Dickens, was surpassed in a single volume, Pickwick Papers, written by Dickens before he was twenty-six years of age. Many of the Dickens characters are with us today, though in more diluted form. it has been suggested that in the nineteenth century, when so many human beings were exploited in the interest of greed, sentimental emotion and religious ostentation served as sedatives for the conscience of the well to do. Dicken’s outbursts against what he considered abuses made more conservative opinion suspect him of radicalism, though for the most part he was unconvinced about efforts for meaningful reform and did protest the vulgar ritual of public executions as spectator activity and the iniquities of the system of lunatic asylums.

Barnaby Ridge is probably the least read of Dicken”s novels but it contains one deliciously worthy of attention character; Simon Tappertit, the little man with big ideas about himself. Tappertit is a more plausible figure today than he was when Dickens created him, and a much more potentially dangerous figure. Our politically correct trend favors the herd mentality and instinct, and when one of the herd, however little, becomes a rogue, he can do as much damage as an elephant. Think Bernard Madoff.

The death of Paul Dombey, in Dombey and Son was moving, but avoided the luscious sentimentality more successfully, or at least navigated his demise more adroitly than the fate that befell Little Ne

n The Old Curiosity Shop. At least the melodrama was more restrained. Dickens wrote to his friend John Forster, “Nobody will miss her like I shall. It is such a painful thing for me, that I really cannot express my sorrow”. Dickens favorite book was David Copperfield.

The memorable characters in David Copperfield seem inexhaustable. David’s aunt, Betsy Trotwood is just the most vivid portrait in the long gallery of old maids sketched by Dickens. Another is Mrs. Gummidge and her determined melancholy, “I am a lone lorne creetur, and everythink goes contrairy with me”. Another is Barkis, the carrier, “when a man says he’s willing, it’s as much as to say, that man’s awaitin’ for a answer,” the answer being to what he considered a proposal of marriage.

What is marked is Dickens portrayal of women, or lack thereof. All his young heroines are pretty dolls, and he lived during a period when, at any rate in England, mot men were still hoping optimistcally that women really were dolls. Dicken was essentially a man’s man and really knew very little it appeared, if anything about the minds of women, however well he could paint their external features. They simply lack dimension and complexity.

Dickens is clearly out of fashion today today. But, at one time Shakespeare was also equally derided by the avant-garde of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. those of us who feel like anachronisms today, as far as literary tastes are concerned, can always reassure ourselves by reflecting that once upon a time Shakespeare was out of fashion.

“I remember two distinct emotions when I finished reading David Copperfield: disappointment and the warm satisfaction that accompanies accomplishment. The disappointment was because the novel is all encompassing – a time machine back to Victorian England.The feeling of accomplishment was more complex….The accomplishment came from a simple fact: No one reads Dickens anymore. … So what I meant to say was: No one mainstream reads Dickens anymore….The second problem for today’s readers is plot. Dickens has too many and, often times, they don’t intersect with each other. He has a tendency to get lost. Modern readers like to zip down the freeway at breakneck speeds toward a stated and well marked destination and Dickens is a forgotten dirt road that winds through the country side and really doesn’t get anywhere until it gets there.

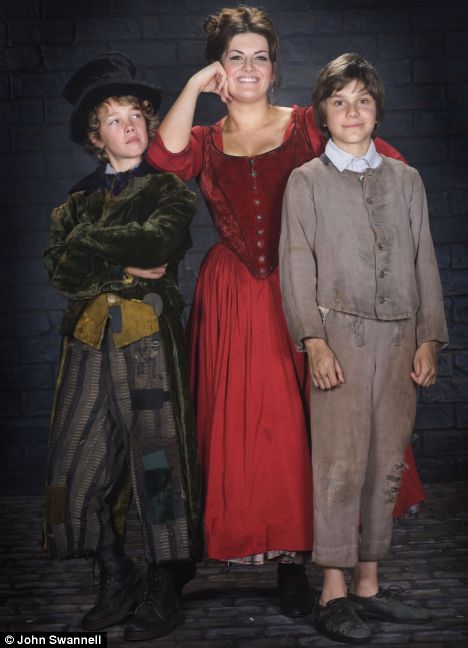

His novels are grand escapades stretching on for years – sometimes decades – featuring dozens and dozens of characters (there are more than 850 different characters in the Pickwick Papers alone). Some of the characters are gigantic – larger than the books where they came to life: Scrooge, Tiny Tim, the Artful Dodger, Fagin, Little Nell, Pip, Sydney Carton, and Mr. Pickwick himself. That, too, can be a distraction. So it takes a long time to wade through one of Dickens’ books and that can be maddening for modern readers….But Dickens is one of the few writers who capture life – a stunning literary achievement. Reading Dickens is to experience humanity. He deserves to be read – to be experienced. You meet people in Dickens – not characters. When you finish one of his novels, you feel rewarded – like you have recieved a very special gift.”

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had … ( Opening A tale of two Cities ) The times have indeed changed. Dicken’s civilization and its standards were founded on what William James called “the gospel of work”, where he majority of people had to work to support a leisured minority. The potential reality is reversed today. If we avoid the solution of Aldous Huxley in Brave New World, where technological progress is arrested; and a third of the population is kept on the land and the rest are usefully occupied in “congenial” jobs, we could smirk at the satire of killing utopias, if his work had not contained an element of inescapable truth. Most of humankind is kept in nervous equilibrium only by conditioning and lies, with a wary eye on technology running amok. At issue is how to relate to Dicken’s work when he contexts seem alienated from present reality and the texts appear as historical anecdotes and an exercise in sentimental romanticism.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS