An antipathy to the material world and to the world of government, order discipline, and force went beyond a form of heresy. It is a constant theme in most religions. Think of Saint Francis, the son of a prosperous merchant, who divested himself of all material things and treated all that lived; birds, beasts and insects, as aspects of god. He pursued poverty like a lover and preferred the broken, the tormented, the simple and the foolish. He and his followers battened on the conscience of the material world that they despised, taking the food, the alms, the shelter, as the hippies did in Haight Ashbury. In the West, religion that is intense, personal and deeply felt has always been at odds with the world it has to live in.

Yet no matter how closely one compares the secular heresy of the Woodstock nation, with its total rejection of the principles and morality of the middle class establishment, to he religious heresies and movements of the past, or indeed sees it as part of the cycle of rejection of the materialism that has been a constant factor in Western life and thought, there remained very important differences. The hippie world, and part of Woodstock nation was compounded not only of social heresy, but of acid. This was a principal differentiation with the past.

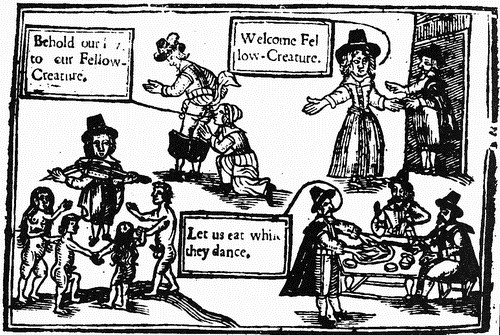

The English Ranters practiced free love, nudity, and pipe smoking, as shown in a 1650 woodcut published by possible Thomas Webbe

Artists, particularly from the nineteenth century onward, sought powerful hallucinations through drugs. Opium, hashish, laudanum etc. became popular in bohemian and artistic circles in the 1800′s, a process that may have peaked with Rimbaud. But the experimentation was a means to art; an attempt to heighten consciousness for art’s sake and not a way of life. For the hippies, it appears, God scarcely existed, having been replaced by a vague sense of the oneness of humanity that was insufficient to create the heightened consciousness needed for hallucinations or ecstatic experience.

The death of the American dream and the increasing feebleness and implausibility of a tenacious myth may have been one reason. Especially if myths can only be sustained and given meaning by the needs of society. That aspect of American society, half-dream and half reality, had lost its social dynamic. Pioneer America became meaningless not only to hippies, but to the nation at large. Disneyfication and commercialization had monetized the spirit and paralyzed its expression. Escape became easier within oneself. Indeed, there may have been nowhere else to go. At the same time, there was the beginning of the contraction of opportunity for the middle class, the same conditions that earlier led to the formation of medieval heretic and Quakers.

The acceptance of failure and the withdrawal from society were satisfying solution to this anxiety, especially if there is the safety net of middle class parents. Counterculture was part lifestyle and hobby; a place to park your identity until greener pastures or a more stable direction arose. Religious heresy was rare among the abject poor who seemed to show a preference for saints and miracles. And hippies were not common in the African American ghettos. The counter was largely the waste products of extensive univesity education systems, often dropouts who were creatively or intellectually unsuited to the intense competitive system of a Horatio Alger America, a society of perpetual upward mobility and relative ease of rags to respectability.

Woodstock Documentary. Michael Wadleigh

iv>One of the most disquieting aspects of the hippie movement was the cultivation of the American Indian, such as by writers like Carlos Castaneda, and the turning away from the African American and his problems which created a central social and political crisis. Lucy may have been in the sky with diamonds,you could sleep on a surrealistic pillow, but it was the African American in the ghetto who really mattered.

”These are the poor; and amongst them there is no grace of manner, or charm of speech, or civilization, or culture, or refinement in pleasures, or joy of life. From their collective force humanity gains much in material prosperity. But it is only the material result that it gains, and the man who is poor is in himself absolutely of no importance. He is merely the infinitesimal atom of a force that, so far from regarding him, crushes him: indeed, prefers him crushed, as in that case he is far more obedient.” ( Oscar Wilde, The Soul of a Man )

Medieval heresies rarely lasted. They were quickly rendered ineffective if not obliterated, like the hippie movement. Even the Ranters were quietly absorbed by the Quakers, who disciplined themselves to live alonside, if not within, the society they were antagonistic towards. Other heresies, less ecstatic and more socially oriented, such as those that occurred at the Reformation, established themselves successfully. It appears that the growth of dissent is somewhat in proportion to the means of communication that are available.

Hippies were news that were exploited by all means of mass communication and their message and way of life spread in the briefest possible time. And they provided, by their dress, music, posters and pot, a quick buck for the taking by the more commercially adroit. The consumer society they disliked fertilized their growth and established an orthodoxy and dogma of sorts,a common propaganda, to be spread internationally in a way that the Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs never did.

Is there resonance between the hippies and the situations in our society today? In particular, the environment, and globalization. Throughout history, creative youth has rarely been drawn to an adult world, but it has been forced to accept it, obey it, and try to reach a compromise since the weight of society is so immense. The opportunity for rebellion is made easier today because society has waning faith and confidence in its economic and political institutions which overflow with hypocrisy and luminous decay. Social institutions are not eternal, and their inability to adapt and innovate,and their tendency to centralize and monopolize decision making has created a reactionary beast.

” The virtues of the poor may be readily admitted, and are much to be regretted. We are often told that the poor are grateful for charity. Some of them are, no doubt, but the best amongst the poor are never grateful. They are ungrateful, discontented, disobedient and rebellious. They are quite right to be so. Charity they feel to be a ridiculously inadequate mode of partial restitution, or a sentimental dole, usually accompanied by some impertinent attempt on the part of the sentimentalist to tyrannize over their private lives. Why should they be grateful for the crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table?” ( Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man )

The success of the Woodstock nation, were its social targets in the adult world such as marriage, monogamy and family life; their attacks on the institutions not of political life, but of adult living. This seems to have ben achieved by a certain intellectual content and strong emotional drive. The hippie movement in general, seemed caught between two opposing forces. That is, flight from the intellect and an escape from reality , and those wishing to confront reality, by capturing it and changing the satus quo with a certain sometimes vague ideology that went beyond mere attitude. To work within the realm of the reality and the ideal. This was exasperated by the gulf between avowed intention and action, such as Vietnam leading to a form of moral bankruptcy, perhaps a precursor to the present recurring dynamic in Afghanistan and environs. Ultimately, the hippies played as dangerously with social passions as any heretic played with religious passions in the Middle Ages through a sometimes inflammatory rhetoric by the likes of Abbie Hoffman and others.

The American dream, like America’s so called ”manifest destiny” is pretty much dissolved, giving way to a future perhaps more filled with suffering than of hope. America’s seemingly insoluble problems has resulted in a certain crushing and flattening of liberal attitudes, what Congressman Ron Paul refers to as a ”creeping fascism”. To quote Yogi Berra, ”its not over until its over” and whether the Woodstock nation and their descendents, including much of the readership here, are regarded as sympton and not a social force is still yet to be determined and not definitive. Nonetheless, the decadent hypocrisy of so much of America and Canada’s social and plitical morality will continue to produce living phantoms that will come home to haunt them. Patience, this is a marathon.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Thanks, Dave.

Excellent article, David!!! As always, I am very happy to be a follower of your blog!! Keep up the amazing work you produce!!!

Thanks for reading. I’ve been stuck on the Woodstock nation dynamic for more than the usual. Long Slow Distance was a good post. I think these so called movements have to be looked at over a multi-generational period and then within the context of even longer time frames such as the article on the Greek poet Sappho.