”Art and religion have been united from the beginning of all civilization, because of the common mystery of their origin and their magical effect on humanity. Etymologically they are allied. The latin term “ars” was at first used in connection with religion and magic and only later disassociated itself from them both to acquire its specific meaning. Art is individual expression of social phenomena, religion was the social expression of individual phenomena.” ( John D. Graham, Dialectics and Art )

The Ghurids, who built the minaret of Jham, lasted only several decades as a kingdom, yet their prominence in modern south Asian politics reflecs their importance as a dynasty in being able to bring large parts of northern India under their sway. The minaret at jham is important in conveying an increased attention to the aesthetic and iconographic function of non-historical inscriptions, especially Qur’anic texts previously dismissed as meaningless religious formulas or gibberish. In fact, within the factional conflicts within the Muslim world, they served a key function as discursive statements deployed in the service of medieval intra-Muslim polemics.

Important to remember; Islamic art is a rubric that must accommodate almost 1400 years and several continents and is far from the culturally monolithic impression many in the western world assume. That is, particualr and competing religious identities are subsumed under the generic terms Islamic or Muslim which assumes and produces an effect of homogeneity.

The minaret at Jam stands almost sixty-five meters high in a remote mountain valley that is diificult to access and susceptible to flooding. Its existence came to the attention of Afghan and foreign scholars only in the 1950’s. The Ghur dynasy was short lived, but among art historians the minaret has assumed canonical status as a cynosure of medieval Persianate architecture. Still, its a mystery on many levels. Much of the minaret is covered with script ranging from .5 to 3 meters. The to section is religious, the middle section is bombastic hommage to the Ghurid sultanates; but on the lower rungs, the form and content of the inscriptions are unique in the Islamic world. They contain the text of the Surat Maryam which relates to Mary, mother of Jesus.

The presence of the Sura may be related to some specific event commemorating the building of the minaret. Since that time the raison d’etre of this long inscription has been one of the enduring mysteries of Islamic art history. It seems to commemorate a Ghurid military victory against Indian rulers which paved the way for Islam to enter India. In light of this interpretation, references to idolatry and unbelief in the chapter of mary description have been read as alusions to the conquered Hindu subjects of the sultan. Still, this does not resolve the central mystery; why was it felt necessary to cover the surface of this remote structure with the entire Suryat Maryam?

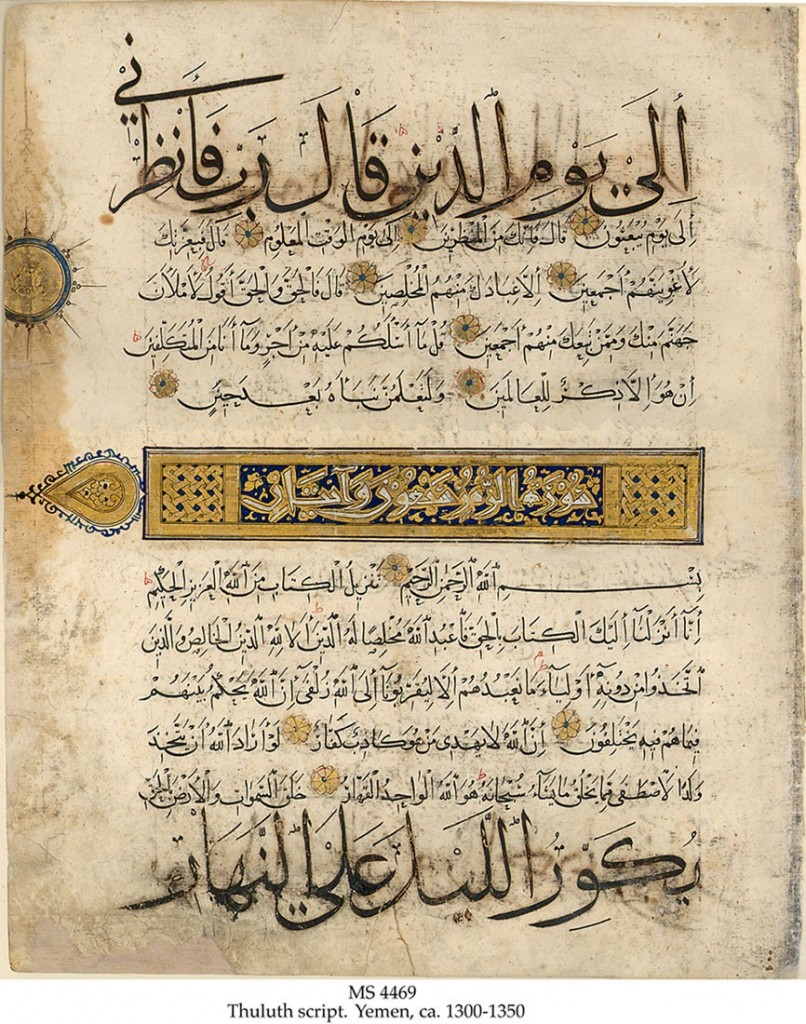

Part of that response may lie with the Ghurid Qur’an. A calligraphic manuscript that contains passages which run counter to Moslem orthodoxy, sparking intellectual sectarian violence that appears problematic and not reconcilable. Among the most theologically problematic verses in the Ghurid Qu’ran are those that seem to imply the divine possession of corporeal attributes and qualities, apparently contradicting or at best, undermining the notion of an eternal and uncreated deity that was central to Islamic thought.

Rather than address to some nebulous monotheist or polytheist other, then, the central epigraphic program of the minaret should be understood as a bold address to the fractious monotheist self. At the heart of the decorative scheme, in the focal inscription of the minaret, appears a distillation of the themes of prophecy, revelation, promise and warning central to the Ghurish or Karrami school of Muslim belief. The same themes are reiterated at regular intervals throughout the Surat Maryam, which invokes a star studded cast of ancestors and prophets including Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Adam, Noah, John, Jesus and others. However, the highlighted verses on the minaret also reject Christian belief in Jesus’ divinity which contradicts the notion of ”tawhid” , the oneness of God, that is central to Islamic thought.

Seen in this light the minaret represents a remarkably sophisticated synthesis of architectural form, decorative elaboration, and epigraphic content that opens a unique window onto the complex entanglements of architectural patronage, dynastic aspirations, legal proscriptions, and theological disputations in the turbulent marches of the Eastern Islamic world. Thus, construction of the minaret was not a heuristic enterprise, but one that reflected a great deal of planning.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS