Hell, the devils and the torments of the damned. From fire and brimstone Christianity, to the murky byways of Judaism’s deepest recesses, the horrifying separation of moral wheat from the chaff and the swift descent into hell have always been artistically captivating because of the varities of tortures; infinite in ingenuity, infinite in pain, and infinite in time.

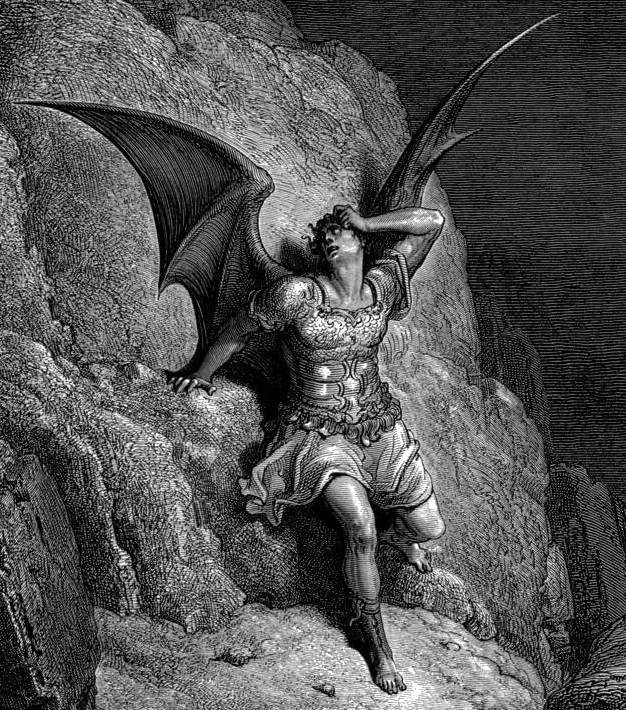

Gustave Dore and other artists like him conceived the devils as angels, fallen and comparatively modern in face and figure. Antatomically, they are men, with noble and strong torsos and limbs. Only the addition of big bat wings and long snaky tails, together with a savage, rather Mongolian expression, confirms that they are demons of the pit. But, evil ought to be more repulsive and more terrifying. A separate category that is not good misplaced and misapplied, but the very reverse of good. Something unrecognizable even as virtue perverted.

Pieter Bruegel and his influence, Hieronymus Bosch have done portrayals of hell and devils, that are highly satisfactory in this regard and likely to receive the approbation of Dante himself. The two Flemish artists lived and worked between 1460 and 1570; they did not know each other, but Bruegel got much of his training from copying the brilliant paintings and engravings of Bosch and adapted many of Bosch’s mysterious ideas.

Both Bruegel and Bosch have several pictures showing hell or the activities of the fiends. Devils tempt St. Anthony, haunt the bedside of a dying miser, or carouse in a mindless hell of lust and vapidity. But the strangest of all their infernal pictures is a surrealist masterpiece by Bruegel. It is a mystical painting, by a mystical artist. It is called ”Dulle Griet” which means Mad Maggie. It is a big picture; five feet by four feet, painted on a wooden panel, not in oil, but with mineral colors mixed with egg.

The picture likely takes its name from the central figure of a slender woman in her middle forties. Over her ordinary clothes she is wearing some of a soldier’s armour. There is a steel breastplate, one huge metal gauntlet, a metal helmet and in her right hand she carries a strong sword. Her eyes are wide open, staring in some excited intensity; her face is thin and haggard, with a pointed nose and wrinkles of tension around her toothless mouth and on her drawn jaw and neck. Her lips are parted, either in eagerness or in the beginning of a shriek. She is a woman who has turned into a soldier. Not only that, but a conquering soldier, for she is loaded down with loot and plunder. Wherever she has been on her expedition, she has done well.

The question is about time; where she has been and where she is at present. Astonished bewilderment aside, its not initially apparent before the context begins to develop. The point of departure is realizing that this is not a landscape on this earth. The sky is not blue or white, but red and black, and lit by lurid fires and striped by pillars of smoke. There are a few strangely shaped trees, but no fields or signs of regular human life. A river runs across the front of the picture, but it is not a normal river. It has been made into a moat for a strange fortification. The building on the right is more or less normal, but that on the left, leaves question as to whether it is a building or monster. Its mouth, where the water pours in, or out, is ringed with fierce teeth. One of its round windows has become a huge round glaring eye. The thing is both a house and a head; it even has a nose with a ring through it.

With Maggie, we are not sure if she is still on the warpath or with her sword, armor and loot or whether she has finished her work for the time being and wants to take her haul to a place of safety. Besides her, there is only one group of normal human beings in the picture. They are all women, dressed in workaday clothes; but instead of doing workaday chores and activities, they are engaged in a battle that looks like a hideous nightmare. They are fighting and beating a group of monsters. Toadlike, apelike, swollen and twisted into shapes like distorted embryos, the monsters in vain struggle against the women, who slap them and buffet them and thrust them aside and trample them underfoot. The women have broken down the doors of the fortress, they have crowded their way inside, and they are coming out laden with booty, like Mad Maggie herself.

pand(this)" href="http://www.solarnavigator.net/mythology/mythology_images/satan_the_devil_painting_by_Michael_Pacher.jpg">

Saint Augustine and the Devil, Michael Pacher

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

It is top of literary-journalistic articles. I wish to discuss with you the rights to the publication if it is interesting to you.

My mail.

Thanks,

an ok article, glad you liked it.