”Picasso had never been a political artist, and as Jung noted, his images seemed increasingly to withdraw from objective reality and primarily reflected some inner psychic state that he was trying to work out on canvas. He made no war-related art during World War I and after the war he turned from the cubism that he had invented and began painting figures in a neo-classical way, a move that might have been a parody of such art. Later he turned to an increasingly obscure version of surrealism that involved bizarre and unsettling distortions of the female form, possibly a reflection of his troubled relations with women.”

Picasso has never offered a key to the symbolism of ”Guernica” , on the basis that he was painting a picture , not writing a book. But most of the symbols are clear enough. The severed arm at the bottom center of the picture holds a broken sword, the classical symbol of heroic defeat, and hence must be a tribute to the Spanish loyalists whose partisan Picasso was, and by extension a tribute to all men who die in a just cause. The bull rising triumphant over the carnage at the far left is a familiar symbol of violence, and one that Picasso had used before, both in connection with the bullfight and as variations of he classical Minotaur.

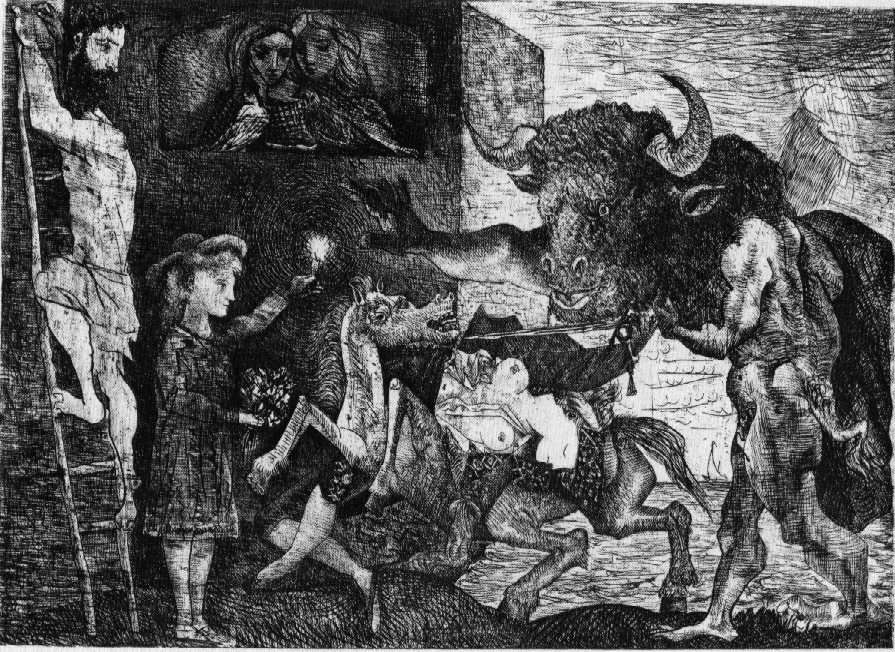

”Throughout the 1930s Picasso had increasingly depicted himself in the guise of the bull and the minotaur, half-man, half-bull. In his Vollard Suite of etchings, again and again the potent minotaur violates, rapes, caresses and treats with tenderness his beautiful, voluptuous, female victim. Picasso loved in-jokes, secrecy and the rituals of ancient Mediterranean cultures. Fascinated by the Roman cult of Mithraism and the ritual slaughter of the bull by the Sun God Mithras, Picasso places the bull’s head between a jagged naked light bulb, a crowing cock and a screaming mother – the Virgin Dolorosa (paraded through every Spanish street during Holy Week).What are we to make of Guernica’s confusing compendium of images weighted so heavily with religious content? The Bull watches the sacrifice. If it is Picasso is it a mere impotent witness? Or, is it the cause of this tragedy?”

The human horse that dominates the center of the picture might also be a reference to the bullfight, where the horses of the picadors, before laws enforced the use of protective pads, were expected to be gored in the preliminary stages of the sport and hence might be regarded as innocent sacrificial victims to the makers, or the gods of violence. Other symbols may suggest themselves: the flower that rises almost like a ghost just behind the hand holding the sword could be prophetic of renewed life that rises from seed, the generative forcethat persists in spite of our wholesale destruction and killing.

”The horse’s screaming dagger-shaped tongue and its death-head nostrils focus our attention directly on the terrible pain and suffering that pulls us repeatedly back to witness the horror. If this is a bullfight it has gone horribly wrong, defying all logic of the corrida. No horse is ever run straight through with a spear in a plaza de toros, as the horse of Guernica has been. In an early version, hidden under layers of paint, Picasso had bent the horse’s head down to the ground in submissive defeat.Here, in the final version, even in its dying moments the horse remains defiant. It may be the last gasp but down to the right of its crooked knee a plant sprouts a few anaemic leaves as the only symbol of hope. Did the horse represent the Spanish people, Picasso was asked? He refused to answer.”

All of these symbols hold as universal ones with a strength and breadth of meaning surpassing their immediate sources. ”Guernica” thus becomsa humanistic allegory just as surely as is any Renaissance recapitulation of a theme. Its specific reference to time and place is limited, in fact, to the title, which could just as appropriately have been not ”Guernica” but ”War”. The city of Guernica, ancient, holy, quiet, and picturesque, is ignored as a locale. Picasso builds instead, within an anonymous setting, what is apparently a farmhouse with its adjoining courtyard and barn. This shift from the conventional scene of battle, which would have been used by a Renaissance artist, to the scene of total war with its civilian victims, puts Guernica within the twentieth century is spite of its alliances with tradition. The painted forms, also, of course, are twentieth century in their nature, and provide a climax and a summary of the manners in which Picasso had worked during his various periods .

Everything seems to have combined to marshal Picasso’s greatest powers at the moment when the bombing of Guernica would light the fuse for this creative explosion. The tender bu rather sentimental response to human beings that took various forms during the Blue and Rose periods is ennobled and enlarged into a compassion for humanity. The years of cubism, which produced the final disruption of realistic form, had established forever the artist’s right to ignore all natural vision for whatever distortions he found most revealing or most expressive.

”While the World Fair praised the new electricity as a modern “way of overcoming night”, the lights in Guernica went out in broad daylight. The proportions of light in “Guernica” are a witness of this violence. The lamp on the ceiling is made into an exploding incendiary. Light becomes an instrument of violence (The same idea in Adorno’s “Dialektik der Aufklaerung”.): the cone of light right of the centre, which is presented in an abstract way and comes in like a spotlight, is not meant to light up the stage – it (on the contrary) “tears off” the horse’s legs. The cone also splits up the woman lying on the ground, who can just hold up her hand in accusation of this violence. The powerlessness over the atrocity is mostly expressed in the hand which is holding a flower and a broken weapon.”

''. The author demonstrates how Picasso's constant pattern of triangular relationships culminated in his personal crisis of 1935, which, together with the Spanish Civil War, reflecting as it did the conflicts of his internal and external relations, contributed to the production of the works in this group. The artist is seen as attempting to work through and make reparation for envious attacks on the parental objects,...''

This bypassing of the figurative had given Picasso the freest and most certain control in the invention of forms that in their dislocations, intentionally hideous, expressed not only in the rending of bodies but the terrible mutations of flesh and of spirit that the twentieth century had suffered as the backlash of its scientific adventures. Cubism itself had

n seen as an anticipation in art of the disruption of matter produced by atomic fission.These cubist-derived forms of the monstrous and the grotesque are clarified and disciplined by combination with variations on the monumental forms of Picasso’s Classical period. The head of the fallen man at the extreme bottom left of the painting, he who had borne the broken sword, and whose dismembered persistently suggests a shattered classical statue, and the head of the woman holding the lamp near the upper center, are hybrid forms in which the classical profile is a dominant part of a mixed inheritance.

A painting of the power of ”Guernica” requires a catalyst that coincides with a decisive moment in the life of the artist, a moment when his sensitivities are at their keenest. In Picasso’s case the catalyst was the bombing of ”Guernica”, but this came just after he had passed through a disturbed period in his personal life, a period summarized in a personal allegory, the etching ”Minotauromachy” of 1935 which rivals ”Guernica” as his masterpiece.

It is worth speculating upon the fact that both ”Guernica” and ”Minotauromachy” are literally colorless, suggesting that Picasso is first of all, a graphic artist, whatever his achievements as a painter. Anyone would normally expect ”Guernica” to be painted in the habitual colors of war replete with blood and flame. But ”Guernica” is now inconceivable in anything other than the blacks, whites, and intermediate greys that have often been compared to a newspaper. There are even passages dotted with small lines running horizontally that suggest lines of type. And the picture is as forceful, as concentrated in spite of its complexity as a headline. As if evil itself, is a monochrome presence, its vulgarity and wickedness masked by a certain subtlety and ”banality”; a painting that can be fully absorbed only by contemplation. The light almost resembles a human eye, as in the Masonic symbol, or as a Sun God expression of even deeper esotericism.

There is also the issue of the geometric horn shapes, or what Salvador Dali popularized as the Rhinoceros horn, which Dali claimed was a mythological form derived from the uniceros; the horn of the legendary unicorn, symbol of chastity. The horn, said Dali, was a divine geometry and the perfect organic shape. The rhino can be a forceful, brutal animal, highly dangerous, but a animal that does not habitually attack unless provoked first. The use of the rhino form in ”Guernica” conveys the sense of violence, but using Dali’s logic, are they asking for their own punishment by holding onto their chastity?

”Dali’s contact with and celebration of the bizarre and unusual persisted throughout his career. Even in a “traditional” mode, he nearly always inserted paranoiac associations where one least expected them. For example, when he set out to create an homage to Vermeer, he painted a study of The Lacemaker composed entirely of exploding rhinoceros horns! To further mystify the public, he painted this piece, Paranoiac-Critical Study of Vermeer’s Lacemaker, at the Paris Zoo. The apparent incongruity of The Lacemaker with rhinoceros horns is resolved upon investigation of Dali’s obsession with perfection of form. The horn is an example of a planar logarithmic spiral, similar to that created in the gnomonic expansion of the golden rectangle. For Dali, the rhinoceros horn was a perfect organic shape, and he often used it in formal deconstructive analysis of pictorial composition. An even more famous example of this sort was the Dalinian masterwork of 1958, Velasquez Painting the Infanta Margarita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory. Created to honor the 300th anniversary of the death of Velasquez, this piece also features the rhinoceros horns, which converge to define the head of the Infanta. It is quite an unusual effect: evocative, beautiful, and yet somehow disturbing.” ( Aaron Ross )

Some have regarded ”Guernica”, as similar to a Renaissance triptych with a large central panel built on a triangular scheme and flanked by two vertical wings. Without being obtrusive, this compositional arrangement is easily discernible in ”Guernica”. Partitioning the twenty-six feet of its length into subdivisions has the double effect of making the painting more readable and, whether or not by intention, of allying it to the religious art of the past. In ”Guernica” there is no separation between historical methods that Picasso has inherited by assimilation and the innovations that he had created as a man vitally receptive to the forces that had determined the character of his time.

No artist of remotely comparable stature has emerged from the generations that have followed Picasso’s. The artists of the dozens of aesthetic generations that have succeeded one another quite rapidly during the same decades have been compartmented into a variety of isolation wards, or laboratories, where they have explored and exhausted one movement after another, each taking its place as the ”new art” and popular flavor. Towards the end of Picasso’s life, a few non-conformists such as Leonard Baskin and Andrew Wyeth, the first with his humanistic reflections upon death, and the second with his lyrical perception of nature, were artists who continued legitimate traditons; However, they were neither prophets nor, in any strict sense, men who seemed much affected by the revolutionary of their times. Even Jean Dubuffet, who was more aggressively ”modern” was as much a culmination of the surrealist and fantastic art of the first half of the century as he was a new voice.

”Picasso portrayed the horse in the Guernica in relation to bull to connote and play on the themes of domestication, innocence, and sacrifice. By portraying the bull fight untraditionally, the horse takes on the central figure as the powerfully victimized. Author Hershcel B. Chipp of “Guernica: Love, War, and the Bullfight” describes the rhetorical reasoning behind straying way from the traditional bullfighting relationships. Chipp states:

In avoiding completely the man-bull contest, the most meaningful and hence most emotionally charged episode, and instead of choosing the bull-horse encounter, Picasso provides a context which, precisely because it lacks ritual significance, offers vaster potentials for the expression of wider meanings. The pathos of the suffering horse lends itself to the subject of the suffering victims of Guernica, just as it had served to express states of suffering in Picassos own years of personal conflict. (Chipp,106).Chipp’s view provides context for Picasso’s specific choice of arrangement in the Guernica of the horse as the central figure literally in the limelight of the light-bulb, and the bull hidden the darkness of brutality. The bull is the least engaged member of the scene, as he watches out from the shadows. Marrero describes the bull in the Guernica as he “triumphs over the work desolation and chaos, wherein the cry of being sacrificed to the cruelty of the world rings out,”(Marrero, 67). The weeping woman with the dead child wails while looking up at the distanced and shrouded figure of the bull. This idea of “being sacrificed to the cruelty” rings true to the sacrifice of the town Guernica, because in fact, Franco “sacrificed” Guernica rhetorically instead of a damaged city or one that had been heavily involved in the civil war because it would not give the same results as a city that was untouched by war (“Guernica-1937”). In other words Franco was making the statement that if any rebel groups stood against him he would turn the Fascist Nazis on them.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

“The head of the fallen man at the extreme bottom left of the painting, he who had borne the broken sword, and whose dismembered persistently suggests a shattered classical statue”

Good morning Dave,

Stricken silent here recently!

I think you need to add “arm” between “dismembered” & “persistently”

On the other hand, “dismember{ment}” might be accurate too?

Maybe i am reading too much…?

Mid-way thru this piece and i couldn’t see the cock crowing.

It had been pointed out to me once before….

Ah i see again

http://umlautampersand.files.wordpress.com/2008/06/guernica.jpg

I see the architecture of human or Cultural life and am inclined to see the cock on the kitchen table. The horse & the cock are are torn thru by a kind of metaspace whereas all the other symbols are/torn thru by light. There seem to be light blues radiating/reflected(?) from beneath the table across the painting to the figure in the barn and the calf or ankle of the woman (i would say) falling to the ground.

So, yeah. Half way thru your piece and hence, a new “understanding” from

dismembered bodies of the beloved balanced with dismembered souls continuing in impotent bodies. It’s something to witness, something to experience. If i gather you, it suggests Picasso will never quite think of art or his art again – at least not in the way of sameness, but rather as persistently or perpetually mediated by a symbolic discourse unable to resist the facts of the real, however violent. Here, the facts and the future are as clear as the vestigial traces of the grid he used to block out the painting.

OK. foreward.

-mason

To be fair, I don,t understand the painting in its entirety myself; just try to catch a few loose threads and hang my coat on a hook that won’t fall down. I think your analysis is better than mine.

Now i gotta understand Minos!

Also, to look up H.G. Clouzot.

Thanks for the Work, Dave!

-mason

Dave, that’s nice of you but i’m simply following your lead. Before reading your work i hadn’t the slightest idea of what is really happening in Guernica, let alone in Picasso’s career.

Much appreciated, as always, mason