Machiavelli: the name leaves no one indifferent. Perhaps one of the most hated men in history among a gallery of rogues. He has been charged, down through the centuries with being the sole poisonous source of political monkey business, of the mocking manipulation of men, of malfeasance, misanthropy, mendacity, murder, and massacre; the evil genius of tyrants and dictators, worse than Judas, for no salvation resulted from his betrayal. He is guilty of the sin against the Holy Ghost, knowing Christianity to be true, but resisting the truth. He is regarded not as a man at all, but Antichrist in apish flesh, the Devil incarnate, Old Nick, with the whiff of sulphur on his breath and a tail hidden under his scarlet Florentine gown. Would you buy a used car from this man?

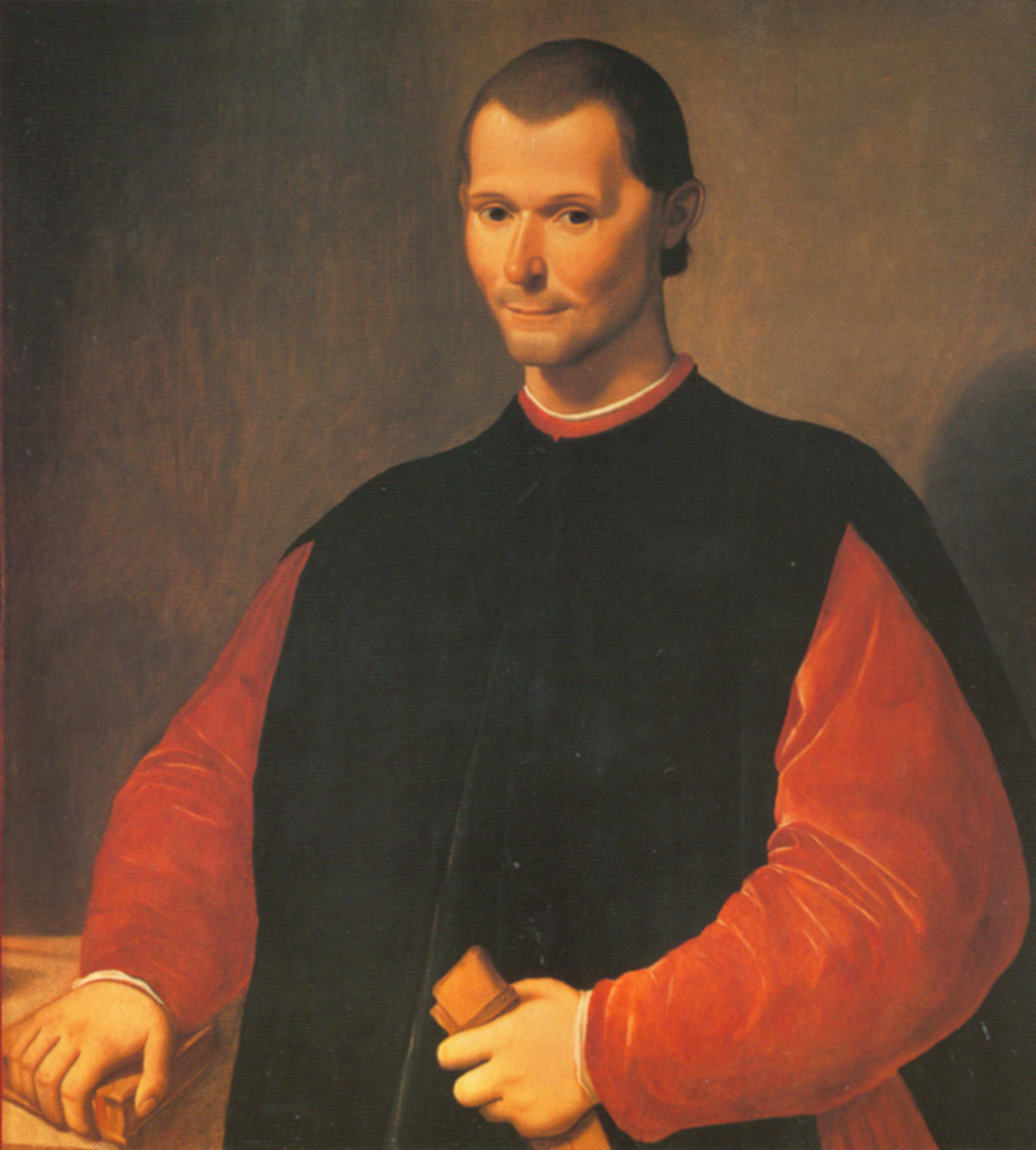

Grasping hands and a secretive half smile mark Santo di Tito's portrait of Machivelli, likely painted after is death.lli

Machiavelli is the one Italian of the Renaissance we all think we know, partly because his name has passed into our language as a synonym for unscrupulous schemer. But the real Niccolo Machiavelli of Florence was a more complex and fascinating figure than his namesake in the English dictionary, and unless we ourselves wish to earn the epithet Machiavellian, it is only fair to look at the historical Machiavelli in the context of his age.

He was born in 1469 of an impoverished noble family and attended The Studio, Florence’s university. Like all of his generation he idolized the Athenian and the Romans of the Republic, and was to make them his models in life. This was one important influence. The other was the fact that Florence, under the Medici, was enjoying a period of peace. The city had, for centuries, been torn by war and faction, but now in the realtive serenity, Florentines were producing their greatest achievements in philosophy, poetry, history, and the fine arts. This is key to understanding Machiavelli; for the first time in centuries swords were rusting and fortress walls became overgrown with ivy. Michelangelo painted bloody battles, but they were battles that had taken place many years before.

This idyllic situation was shattered in 1994 when King Charles VIII of france invaded Italy to seize the kingdom of Naples. Florence lay on the route and the effete Pietro de Medici succumbed quickly. The debacle led to internal wars, economic decline and the rise of a puritanical revolution headed by Savonarola the Dominican . Thundering that the French invasion was punishment for a pagan way of life, he burned classical books, ”vanities” and urged a regeneration of Florence through fasting and prayer. He himself ended up burnt at the stake in 1498, the year in which Machiavelli became a diplomat and administrator of the Florentine Republic. He persuaded the Florentines to form a citizens militia and in 1512, Florence’s big test came by route of Spain which had replaced France as Italy’s oppressor. Machiavelli’s militia fought without heat, Prato was sacked and Florence surrendered. The Medici returned and the Republic came to an end. Machiavelli lost his job, was tortured and exiled to his farm. For the second time in eighteen years he had witnessed a defeat that was both traumatic and humiliating.

''Phil Regal muses at Machiavelli Painting, While Visiting Political Science Department, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1999.''

The following year, the then unemployed Machiavelli began to write his great book, ”The Prince”. It was an attempt to ask the question of what had gone so wrong in Florence’s two terrible defeats. The answer was that for all their classical buildings and fancy art, and all the readings of Plato, the Florentines had never really revived the essence of classical life which was the military vigor, patriotism and bloodlust unto death that distinguished the Greeks and Romans. The remedy was regenration, not by the puritanism of Savonarola, but by the soldier-prince. This prince must subordinate every aim to military efficiency. He must personally command a citizen army and keep it disciplined by a reputation for cruelty.

Even this, reasoned Machiavelli, would not be enough to keep at arms length strong nation states like France and Spain. So, in a crescendo of patriotism, Machiavelli urges his Prince to disregard the accepted rules of politics and to hit below the belt. The art of the lie must be perfected in order to violate treaties and the honor of word should be disregarded when the context no longer favored its prince. It was the virtuous art of the non virtuous behavior.

Macchivalli’s ideal soldier-prince in his conception is the archetypical strongman capable of ferociously violent spectacles able to leave his populace content and horrified at the same time. Nothing like a good public exposition of mutilated corpses to get the message across. Machiavelli had a peculiar cast of mind. He grows excited when goodness comes to a sticky end and when a dastardly deed is perpetrated under a cloak of justice. He seems to enjoy shocking traditional morality, and there can be little doubt that he is subconsciously revenging himself on the establishment responsible for those two profound military fiascos.

Machiavelli wrote ”Th

ince” for Guiliano de’ Medici. However, Guiliano , the youngest son of Lorenzo the Magnificent was an effeminate and soft man, sickly, and not constitutionally inclined to rule with an iron hand. He died young. Macchivelli’s notion of turning him into Cesare Borgia was as fantastic as trying to transform John Keats into James Bond.

This fantastic element has been overlooked in most accounts of Machiavelli; his histories recounted in ”Life of Castruccio Castracani” is loaded with fictitious episodes that expand on the unscrupulous actions of past tryants,now attributed to his new subject, so that a mildly villainous Lord is dressed as the perfect amoral autocrat. In both books, Machiavelli is so concerned to preach his doctrine of salvation through a strong soldier-prince that he leaves Italy as it really was for a world of fantasy.

Machiavelli also had a second purpose with ”The Prince”, that being to ingratiate himself, and regain favor with the medici, notably with Pope Leo. This also was a fantastic plan since machiavelli had plotted hand over fist against the Medici for no less than fourteen years and was known to be a staunch Republican, opposed to one-family rule in Florence. Pope Leo, moreover, was a gentle man who loved Raphael’s smooth paintings and singing to the lute; he would not likely be interested in a book counseling cruelty and terror.

How could a man like Machiavelli have yielded to such unrealistic and fantastic hopes? It is likely that he was also an imaginative playwright obsessed with extreme dramatic situations. Indeed, Machiavelli was best known in Florence as the author of ”Mandragola”. In that comedy, a bold and tricky adventurer, aided by the profligacy of a parasite, and the avarice of a friar, achieves the triumph of making a gulled husband bring his own unwitting but too yielding wife to shame. Thus, it is an error to regard Machiavelli as primarily a political theorist taking a cool, detached and objective look at the facts. ” The Prince”, is in a certain sense, the plot of a fantastic play for turning the tables on the French and the Spanish.

”His advice in conquest to embrace the powerless opposition while keeping them powerless, and domestically to use consel without letting the counsel lead, has likewise not been rediscovered in many an adminstrative post-mortem. There remains a problem of the extent to which a foreign prince is damned by failure tounderstand the local power structure very well, or the local customs, or even the extent to which he can. (I’m reminded of recent readings ofGraham Greene, say, who’d eloquently novelize its inherent doom, and Howard Zinn, who reported the success of stamping out customs and local power on the North American continent, both voicing the people’s views of history instead of a prince’s.) Machiavelli’s advice to project an image of honesty, respect, and fear which is at odds with any personal qualities a leader may have is almost too widely taken and obvious to mention these days, but still, it’s best not ignored.”

…and there’s a strange undercurrent in the writing where, he instructs a prince to power, but the message that he must never earn their contempt through oppression (through theft and disrespect of their customs–they get past love easily enough) or displays of weakness, seems at odds with the contention that a populace allowed to remain accustomed to freedom will eventually overthrow a prince (or will be able to hold out for a weak one). Nor does Fortune, according to Machiavelli, favor the longevity of princely rule. The Prince is a stark lesson on how to be a monarch, but it doesn’t really justify monarchy. Aside from that final urge to cast off Italy’s foreign bonds, Machiavelli fails to ask the obvious question, the one that contrasts so oddly with his advice to let the people be the people: what good are princes in the first place? They’re a natural way to organize society, he implies, but Niccolò the republican also has his own agenda. Are the failures of monarchs built in, and would Italy be better unified under a king, who could then be cast off? Machiavelli is certainly smart enough, and cynical enough, to write in a couple layers of meaning.(Keifus )

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

…Love your articles, Dave!…They are most interesting…off the wall…everything I always wanted to know…but was afraid to ask! ;)

Thanks for reading ”inside-out”

Best,Dave