”Through cannibalism, the Aztecs appear to have been attempting to reduce very particular nutritional deficiencies. Under the conditions of high population pressure and class stratification that characterized the Aztec state, commoners or lower-class persons rarely had the opportunity to eat any game, even the domesticated turkey, except on great occasions. They often had to content themselves with such creatures as worms and snakes and an edible lake-surface scum called “stone dung,”…. which may have been algae fostered by pollution ….Another Aztec dietary problem was the paucity of fats, which were so scarce in central Mexico that the Spaniards resorted to boiling down the bodies of Indians killed in battle in order to obtain fat for dressing wounds and tallow for caulking boats….Interestingly, prisoners confined by the Aztecs in wooden cages prior to sacrifice would be fed purely on carbohydrates to build up fat.” ( Michael Harner )

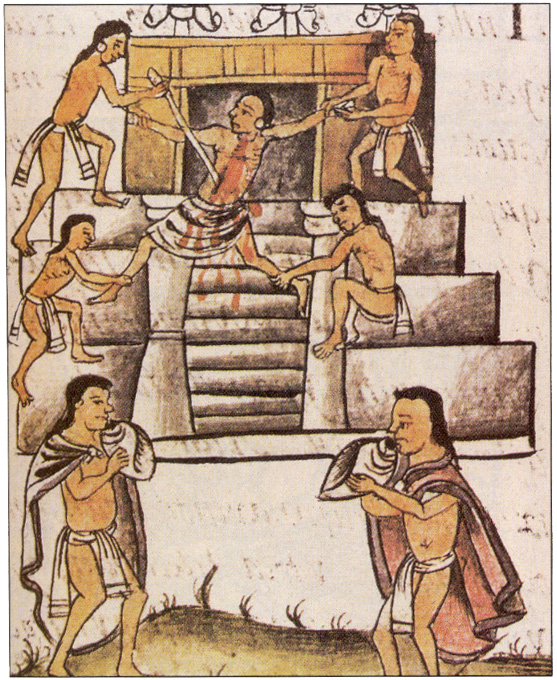

Aztec human sacrifice. '' For the reconsecration of Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in1487, the Aztecs reported that they sacrificed 84,400 prisoners over the course of four days reportedly by Ahuitzotl, the Great Speaker himself.''

Call it the return of the plumed serpent.An ecological prerogative that was in its waning glory.For ten years, Montezuma II, Emperor of the Aztecs, had been troubled by news of strange portents. Comets traversed the skies for hours at a time; the waters of Lake Texcoco foamed and boiled and flooded the capital; the temple of the god of war mysteriously caught fire; and disembodied voices filled the air with groans and lamentations. Worst of all, a bird like a crane, with a mirror on the crown of its head, was captured and brought to Montezuma; and when he looked into the mirror, he saw an ill-omened constellation of stars which suddenly changed into a scene of armed men mounted on deer.

Anxiously, Montezuma summoned his priests and astrologers, and put them to death when they failed to answer his questions satisfactorily. He ordered more slaves to be sacrificed, in the hope of averting disaster. But in his heart he knew, indeed he was soon expressly informed by a talking stone, that it was already too late. For the omens could only presage the imminent return of Quetzalcoatl, the Plumed Serpent, the god king of ”a grave countenance, white-skinned and bearded,” who had long ago been driven from his Mexican kingdom, and would one day come back, traveling from the east, to recover his lost inheritance.

''The Cholultec chiefs received Cortés coolly, and warned him that Montezuma had commanded him to go no further; he was not welcome in Mexico. Cortés also discovered that Montezuma had ordered that the Spanish not be fed by the Cholultecs, a development that greatly alarmed the Spaniards. ''

How are we to interpret the deep anguish of Montezuma at the prospect of the second coming of Quetzalcoatl? At least the portents could be no cause for surprise, for it had long been known that the Plumed Serpent would one day return to assume what was rightfully his. Montezuma’s Aztecs had inherited this tradition from the Toltecs who had inhabited ancient Mexico. Montezuma himself, although the leader of a warrior people, was by temperament a philosopher king deeply attracted by Toltec beliefs. During long hours of meditation in his house of retreat he seems to have developed doubts and uncertainties concerning the contradictions between these older beliefs and the primitive religion of the Aztecs, into which they had been fully absorbed. He was profoundly uneasy about the mood in which Quetzalcoatl would return to his kingdom; he felt a sense of responsibility to his people, and at the same time a personal guilt that Quetzalcoatl should choose his reign in which to return; and he had premonitions, now confirmed by the portents, that it was his fate to preside over the destruction of the Aztec civilization.

”In Mesoamerica, the most obvious practice of human sacrifice was found in the Aztec Culture. Under the leadership of Montezuma and others before him, sacrifice became a key element in their ritual and worship to many gods. The Aztecs were constantly at “war” with neighboring tribes and groups. The goal of this constant warfare was to collect live prisoners for sacrifice. The Flowery Wars began with a mutual agreement between the Aztecs and the Tlaxcalans to capture live men for future sacrifice (Meyers & Sherman)

The Aztecs worshipped a war god called Huitzilopochtli, who took on the likeness of the sun over time. It was thought that in order to insure the sun’s arrival each day, a steady supply of human hearts had to be offered in holy sacrifice (Hogg). They believed that the sun and earth had already been destroyed four times, and in their time of the 5th sun, final destruction would soon be upon them. In order to delay this dreadful fate, the practice of human sacrifice became a major element in Aztec society and livelihood .

''The idea of what ‘barbarism’ is really lies in the eye of the beholder. Although Spanish priests thought many Aztec practices to be base and even evil, they preached in the name of an

re (the Holy Roman Empire) that regularly tortured people for the Inquisition!''The doubts that tormented Montezuma perhaps symbolized, in a heightened and personal form, a mental conflict in the society over which he presided as a semi-divine king. To all outward appearances the Aztec state was strong and prosperous. Since founding Tenochtitlan ( Mexico City ) in 1325, the Aztecs had conquered the neighboring tribes of Central America and helped preserve their domination by an elaborate system of religious terror, whereby the Aztec priests made it understood that the wrath of the implacable deities who ruled the universe could only be averted by a constant orgy of human sacrifice.

''The Spanish Arrival in 1519 changed how the Aztecs continued with their sacrificial ways. Hernan Cortes and the Spanish were glad when King Motecuhzoma sent representatives of the city to see Cortes, but were appalled at the sight of them sacrificing a small boy right there on the beach. ''

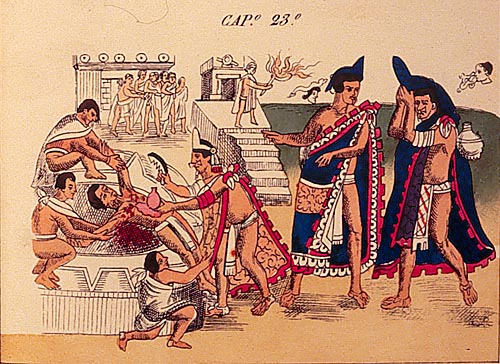

”The most common form of sacrifice was performed outside, on the top of a great pyramid. The victim was spread-eagled on a round stone, with his back arched. His limbs were held, while a priest used an obsidian knife to cut under the rib cage and remove his heart. This method was used when honoring the sun god, Huitzilopochtli. Each god apparently preferred a different form of sacrifice. For the fertility god Xipe Totec, the person was tied to a post and shot full of arrows. His blood flowing out represented the cool spring rains . The fire god required a newly wed couple. They were thrown into the god’s altars and allowed to burn and at the last minute they were taken out and had their hearts removed as a second offering . The earth mother goddess, Teteoinnan, was extremely important. At harvest time, a female victim was flayed and her skin was carried ceremoniously to one of the temples. Her skin was worn by an officiating priest who then symbolized the goddess herself . Human sacrifices were seen in many different cultures in Latin American, such as the Olmec.”

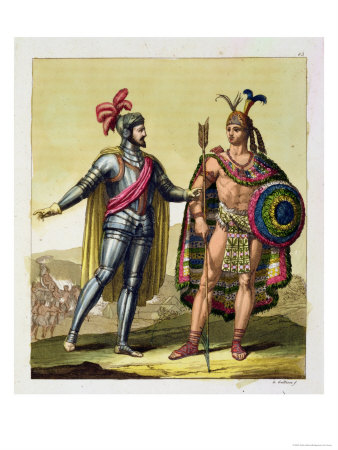

''The Encounter Between Hernando Cortes and Montezuma II, from "Le Costume Ancien Et Moderne" Giclee Print by Gallo Gallina''

But the heavy apparatus of ecclesiastical despotism, decked with all the trappings of blood-stained, had not prevented the evolution among the Aztecs of a vigorous and dynamic society. By the time of Montezuma II this society had emerged from its primitive tribal pattern into a complex state-structure , with a privileged ruling class and a proseperous mercantile community; and the city of Tenochtitlan, with more than 300,000 inhabitants , had become the powerful and wealthy head of the confederation of cities which together constituted the Aztec empire. It is not surprising that these rapid material developments were accompanied by some signs of material stress, and that, well before the reign of Montezuma, the necessity for the endless shedding of human blood had come to be questioned, and various alternative propositions both asserted and considered. Thus, it may be that the insistent reports of the imminent return of Quetzalcoatl served to confirm doubts that Montezuma shared with some of his subjects; doubts about the system of which he was the supreme head , and whether that system would meet with the approval of Quetzalcoatl, a god who traditionally was opposed to the sacrifice of human victims.

”Sixty-two of their companions had been captured, and Cortés and the other survivors helplessly watched a pageant being enacted a mile away across the water on one of the major temple-pyramids of the city. As Bernal Díaz later described it.

“The dismal drum of Huichilobos sounded again, accompanied by conches, horns, and trumpet-like instruments. It was a terrifying sound, and when we looked at the tall cue [temple-pyramid] from which it came we saw our comrades who had been captured in Cortés defeat being dragged up the steps to be sacrificed. When they had hauled them up to a small platform in front of the shrine where they kept their accursed idols we saw them put plumes on the heads of many of them; and then they made them dance with a sort of fan in front of Huichilobos. Then after they had danced the papas [Aztec priests] laid them down on their backs on some narrow stones of sacrifice and, cutting open their chests, drew out their palpitating hearts which they offered to the idols before them.”

Cortés and his men were the only Europeans to see the human sacrifices of the Aztecs, for the practice ended shortly after the successful Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire. But since the sixteenth century, Aztec sacrifice has persisted in puzzling scholars. No human society known to history approached that of the Aztecs in the quantities of people offered as religious sacrifices: 20,000 a year is a common though far from consensus estimate.

”A typical anthropological explanation is that the religion of the Aztecs required human sacrifices; that their gods demanded these extravagant, frequent offerings. This explanation fails to suggest why that particular form of religion should have evolved when and where it did. I suggest that the Aztec sacrifices, and the cultural patterns surrounding them, were a natural result of distinctive ecological circumstances.” ( Michael Harner, The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice. 1977 )

Harner has theorized, backed by considerable research that large scale cannibalism was a consequence of ecological circumstances and was thinly disguised as religious sacrifice. These enormous numbers call for consideration of what the Aztecs did with the bodies after the sacrifices.Harner claims evidence of Aztec cannibalism has been largely ignored or consciously or unconsciously covered up. For example, the major twentieth-century books on the Aztecs barely mention it; others bypass the subject completely. Probably some modern Mexicans and anthropologists have been embarrassed by the topic: the former partly for nationalistic reasons; the latter partly out of a desire to portray native peoples in the best possible light. Ironically, both these attitudes may represent European ethnocentrism regarding cannibalism — a viewpoint to be expected from a culture that has had relatively abundant livestock for meat and milk.

According to Harner,a search of the sixteenth-century literature, leaves no doubt as to the prevalence of cannibalism among the central Mexicans. The Spanish conquistadores wrote amply about it, as did several Spanish priests who engaged in ethnological research on Aztec culture shortly after the conquest. Among the latter, Bernardino de Sahagún is of particular interest because his informants were former Aztec nobles, who supplied dictated or written information in the Aztec language, Nahuatl.

”According to these early accounts, some sacrificial victims were not eaten, such as children offered by drowning to the rain god, Tlaloc, or persons suffering skin diseases. But the overwhelming majority of the sacrificed captives apparently were consumed. A principal — and sometimes only — objective of Aztec war expeditions was to capture prisoners for sacrifice. While some might be sacrificed and eaten on the field of battle, most were taken to home communities or to the capital, where they were kept in wooden cages to be fattened until sacrificed by the priests at the temple-pyramids. Most of the sacrifices involved tearing out the heart, offering it to the sun and, with some blood, also to the idols. The corpse was then tumbled down the steps of the pyramid and carried off to be butchered. The head went on the local skull rack, displayed in central plazas alongside the temple-pyramids. At least three of the limbs were the property of the captor if he had seized the prisoner without assistance in battle. Later, at a feast given at the captor’s quarters, the central dish was a stew of tomatoes, peppers, and the limbs of his victim. The remaining torso, in Tenochtitlán at least, went to the royal zoo where it was used to feed carnivorous mammals, birds, and snakes.”

Thus for various reasons, of which religion seemed to play a secondary and supportive role, the arrival of Cortes was cause for concern. In one word: Anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, and endless rounds of unease, hesitation and fear. An acceleration into an unquiet age where faith became less secure, acquired status uncertain, a moral rigidity less acceptable and social discontent less easy to quell. Montezuma must have yearned for a nostalgia for times gone by that seemed almost obsessive. That the Aztec world might suddenly end was not a new anxiety created by Cortes, but merely an old anxiety renewed. The structure of respectable ritual was threatened.

”In 1946 Sherburne Cook, a demographer specializing in American Indian populations, estimated an over-all annual mean of 15,000 victims in a central Mexican population reckoned at two million. Later, however, he and his colleague Woodrow Borah revised his estimate of the total central Mexican population upward to 25 million. Recently, Borah, possibly the leading authority on the demography of Mexico at the time of the conquest, has also revised the estimated number of persons sacrificed in central Mexico in the fifteenth century to 250,000 per year, equivalent to one percent of the total population. According to Borah, this figure is consistent with the sacrifice of an estimated 1,000 to 3,000 persons yearly at the largest of the thousands of temples scattered throughout the Aztec Triple Alliance. The numbers, of course, were fewer at the lesser temples, and may have shaded down to zero at the smallest.”

In Tristes Tropiques, the French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss described the Aztecs as suffering from “a maniacal obsession with blood and torture.” A materialist ecological approach reveals the Aztecs to be neither irrational nor mentally ill, but merely human beings who, faced with unusual survival problems, responded with unusual behavior.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS