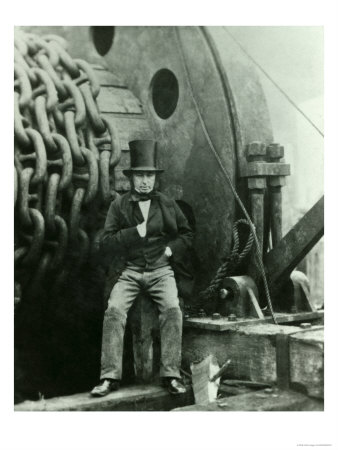

The late eighteenth and nineteenth century was an age that bred giants in the field of engineering. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was the last and, surely, greatest of them all.His life was marked by hugely ambitious projects, unparalleled in engineering history, which tended to become even more ambitious as the years passed.Isambard Brunel ( 1806-1859 ), had, in all, about 2,000 miles of railway built under his direction. This, one might suppose would be more than enough for one short lifetime, but in fact it was only half of Brunel’s activities. In the world of marine engineering he made a mark that was even more sensational than his broad guage railways.

It is said that the ghost of Isambard Brunel is still on the high seas; another example of the ghost ship vessels which continue to journey the oceans with dogged determination when everyone aboard is missing or dead. He is still building and designing ships from the beyond as an engineer from the world of the paranormal who guides a fleet of ragged sailers and rusty hulks manned by the dead. His last great ship, the Great Eastern, was completed after the Suez Canal was re-designed, and the ship was to large to pass through. Brunel has exacted his revenge assuming the helm of the Flying Dutchman, or so the legend says….

This story began at an early board meeting of the Great Western Railway Company when someone expressed misgivings about the length of the proposed line from London to Bristol. ”Why not make it longer ,” suggested Brunel through the smoke of his cigar , ”and have a steamboat go from Bristol to New York and call it the ”Great Western”? Those staid, frocked coated gentlemen of the board accepted this sally as one of their engineer’s characteristic little jokes, but that it was no joke they soon realized when a company was formed in Bristol , which began building the ”Great Western”, the largest steamship in the world at the time.

Once again, the prophets of disaster gathered like ravens. It could be proved by calculation, they croaked, that no steamship could carry enough coal for an Atlantic crossing under continuous power. But Brunel realized they had got their figures wrong; that whereas the carrying capacity of a hull increases as the cube of its dimensions, its area, or, in other words, the power needed to drive it through the water, only increases as the square of those dimensions. Hence, the larger the ship the greater its cruising range without refueling. This was the simple proposition which inspired Brunel to build his first ship and his alleged pact with the devil to build the biggest and the fastest vessel of its type.

”There have also been accounts of the Flying Dutchman’s ship, in a more solid state, hailing passing boats. If communicated with, the dead ship will send over a party of pale, exhausted looking crew members who will hand over letters and request that the ‘living’ ship ensure that these letters are delivered back to The Netherlands. If this mail is investigated, it will be seen that the letters are addressed to long dead loved ones and refer to events and technologies from the mid 1600’s. Acceptance of the mail will always result in certain doom for the ship which takes them on board, as such correspondence is destined never to reach land.”

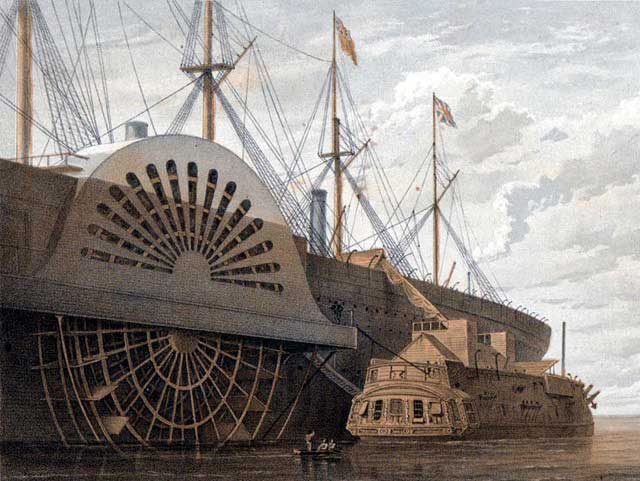

As the ”Great Western” , a wooden paddler with a displacement of 2,300 tons, took shape, established shipping interests began to wonder uneasily about their future if Brunel’s experiment came off. To be on the safe side, the British & American Steam navigation Company of London laid down the ”British Queen” on the Thames at Limehouse. But this ship was stil far from completion when the Great Western arrived in London under sail to take on her engines at Blackwall. Determined to steal Brunel’s thunder if it could, the rival company thereupon chartered the little Irish steam packet ”Sirius” and began to fit her out for an Atlantic voyage. The Sirius narrowly won the race to get the two ships ready for sea.

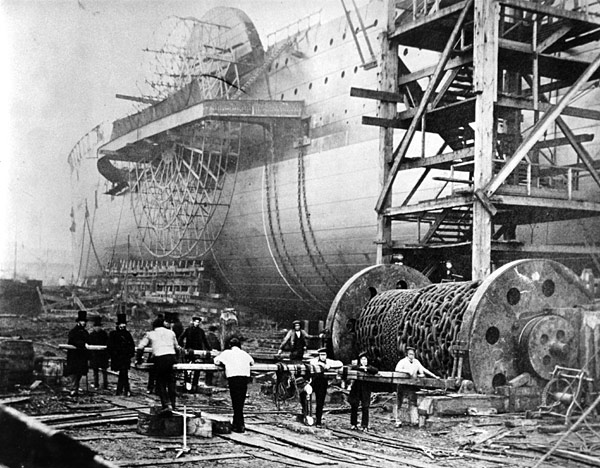

Great Eastern (1854) Brunell's ship used in 1865 to lay the first successful transatlantic telegraph cable (2500 miles) Shown here loading cable

Brunel was not unduly worried about the starting handicap until, before his splendid ship had cleared the Thames estuary, smoke and flames suddenly belched from her boiler room. The boiler lagging round the base of the funnel had ignited and set fire to the deck planking. The outbreak was mastered before any serious damage was done, but it nearly cost Brunel his life. As he was fighting the flames, the charred rung of a ladder collapsed under him and he fell eighteen feet onto the boiler room plating where, knocked unconscious, he nearly drowned in the water that had collected there. In great pain, he was rowed ashore to the care of a cottager on Canvey Island, while on

insistence the ”Great Western” put out to sea after a delay of twelve hours.The legend is that Brunel, made his pact with the devil; in his pain he could not refuse satan’s offer of help to build three ships in exchange for his soul.Brunel became doomed forever to captain his ships on the high seas as he continually plays dice with the Devil in an effort to win back his soul. It has seemed the most plausible reason for the advanced engineering and the extremely fast trips he enjoyed. The speed with which he would sail between distant points was so uncanny, so much faster than anyone else, that he was reputed even in life to have help from the Devil. Because of this pact with Satan, the story maintains that Brunel is compelled to continue sailing his trade route between Australia and Europe, even after death. He journeys in a ghostly ship called the ”Free Us” with a crew of skeletons, moving at breakneck speed with the aid of forces not explainable or identifiable.

''The SS Great Britain was the first iron ship, the first to have a balanced rudder and watertight bulkheads and the first propeller driven ship to cross any ocean. Launched in 1843 by Prince Albert it was the world's biggest ship by far. The engine crankshaft of The Great Britain was too big for any forge to make it. To overcome this, the steam hammer was invented; this became one of the major tools of the industrial revolution.''

…It seemed that the result of the race must be a foregone conclusion, since the Sirius had a four day advantage and the Great Western got away from the more distant port of Bristol. The little Sirius docked in New York after nineteen days at sea. It had been a close call, for her coal bunkers were empty and she had to burn barrels of resin from her cargo. A few hours later, the Great Western dropped her anchor off Sandy Hook, fifteen days and five hours from the Port of Bristol.

The enthusiastic New Yorkers could not then appreciate the really vital point about the demonstration; namely the Great Western still had 200 tons of coal in her bunkers. In that fact, Brunel had triumphantly proved the practicality of transatlantic steam navigation.The Great Western was a complete success and made 67 crossings in eight years. Her best records were thirteen says westbound and twelve days eastbound. She was followed on the Atlantic run in 1845, by Brunel’s second ship, the Great Britain, which like her predecessor was the biggest ship afloat when she was launched. It was also the first iron steamer and the first screw propelled ship to cross any ocean. It is doubtful whether any other man would have had the courage to embody two such revolutionary innovations in one design.

”The final sighting of the Flying Dutchman occurred in 1959, when a Dutch freighter called the Straat Magelhaen reported an extremely close encounter with a ghostly sailing ship. Her sails were full, she was moving extremely quickly, and she was so close that the crew of the freighter could clearly see a lone man steering the craft. Collision seemed inevitable, but the apparition vanished right before impact.”

It was with the object of avoiding costly refueling that Brunel designed the third and last of his great ships, the fabulous ”Great Eastern”. With a displacement of 32,000 tons, fout times the size of any ship afloat at that time, Brunel’s great ship could steam around the world without refueling. However, in designing a ship which was not to be surpassed in size until 1899, Brunel jumped too far ahead of his time. Although two sets of engines were installed, one driving a screw, the other , huge paddle wheels, in those days of low pressure steam it was impossible to provide enough power to drive so large a hull. Although her engines were the largest ever built and indicated 100,000 horsepower, the Great Eastern disappointed in speed.

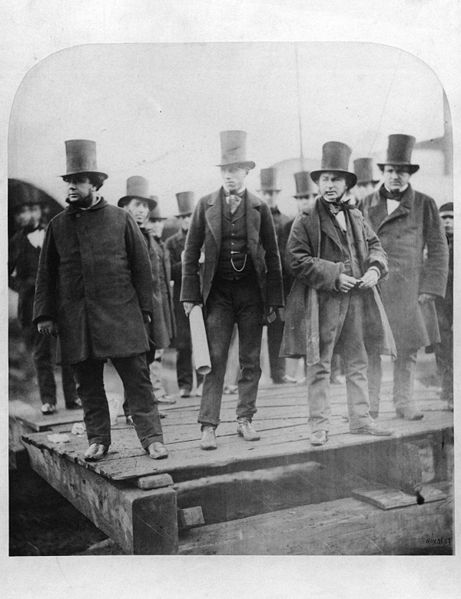

The ship was successfully floated in January 1858, but the production difficulties meant this success had been purchased at a terrible price. Brunel’s health was ruined and the company could not finance the fitting of his ship. Brunel was mortally ill and prematurely aged and never achieved his last ambition of sailing on its maiden voyage. Two days before the ship was due to sail, he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed and the Great Eastern left without him.

She was on her course down the channel when disaster struck. Due to carelessness on the part of the builder, John Scott Russell, and his men who were in charge of the paddle engines and their boilers, a feed-water heater exploded. It blew one of the huge funnels into the air, wrecked the grand saloon, and scaled to death six firemen. The effect of the disaster on Brunel, who lay waiting for news at his home, was tragic. Even his indomitable spirit was broken by the news of this crowning misfortune, and a few days later, on September 15, 1859, Brunel died.

Brunel suffered several years of ill health, with kidney problems, before succumbing to a stroke at the age of 53. Brunel was said to smoke up to 40 cigars a day and to sleep as few as four hours each night.

As a passenger ship, the Great eastern was never a success. It was Daniel Gooch who vindicated both the ship and its designer by equipping her for cable laying, in which capacity she was outstandingly successful. With Gooch himself on board, the Great eastern laid the first transatlantic cable from Valencia to Newfoundland, and she then went on to weave a web of cables around the world.

The most admirable quality of Brunel was his ability to apply design and engineering concepts over a variety of projects ranging from bridges, to railway construction to ships; a versatility of intellect and imagination that wandered amicably between art and science. He is a reminder that the gulfs between art and science are artificial and that specialization is often an excuse to know more and more about less and less.

”However, the typical recorded sighting of the Flying Dutchman does not come from an idle tourist or land-lubber. They come from crew members of warships and large merchant vessels, men with years of experience at sea who have sailed all over the world. They come from lighthouse keepers, whose credibility and ability to recognize objects in the ocean have always been crucial to preventing maritime disasters. Some of those logs, especially those written in World War 2, would have been submitted to superior officers who would hardly have been in the mood for joking around. Even if objects were projected/distorted by mirage effects, how many large sailing ships were still at sea in 1942 during the Jubilee sighting, and in 1959 during the Straat Magelhaen encounter, when both observations were at a reasonable distance and crew members clearly identified the unknown craft as a sailing ship?”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS