After his release from prison in November, 1703, for his satiric and incendiary pamphlet, ” The Shortest Way With the Dissenters”, Danel Defoe became a government spy, the tool of the people who had him freed, mistrusted and hated where it was known. The account against him looks black; in fact, it is nearer gray than black. His defense is that he was employed by the most accomplished of English politicians to insinuate a spirit of moderation in a country full of faction. This is a strong defence; Defoe’s whole nature was moderate and practical.

''After a scandalous life of adventure, bigamy, incest and fraud, the notorious Moll Flanders finds herself in the shadow of the gallows. Her rags to riches tale reveals the cunning of a woman determined to crack the glass ceiling of Eighteenth Century society… by any means necessary! But as she confesses to her life of shame, will this moral outlaw be able to stay the hand of the executioner?''

But then again, Defoe was delighted to be a spy. He loved to travel about England. His false names and pretended occupations excited his imagination. In addition, his journey’s on horseback from town to town, collecting opinions, noting names, finding out about money and trades, gives one of the best accounts of how ordinary people lived in England at that time, what they worked at, work always interested him, and the prices of food, cloth, and so on. He had an ear and an eye for the strange. The population of the eastern fens and marshes in England has always been ”deep” and peculiar. In Essex, it was even more peculiar, for there he found men who had up to fifteen wives.

William Hogarth. Captain Lord George Graham.''First among the 18th century's many gifts to middle-class job-seekers - novel-writing, landscape gardening, journalism - was the art of social climbing. From Defoe's Moll Flanders to Gainsborough's portraits of London high society, writers and artists celebrated a new breed of hero and heroine: bewigged David Beckhams and Chantelles who had clawed their way up to respectability while keeping those below them firmly in their place.''

”…that I took notice of a strange decay of the sex here; insomuch, that all along this county it was very frequent to meet with men that had had from five or six, to fourteen or fifteen wives; nay, and some more; and I was inform’d that in the marshes on the other side the river over-against Candy Island, there was a farmer, who was then living with the five and twentieth wife, and that his son who was but about 35 years old, had already had about fourteen; indeed this part of the story, I only had by report, tho’ from good hands too; but the other is well known, and easie to be inquired in to,…

The reason, as a merry fellow told me, who said he had had about a dozen and half of wives, (tho’ I found afterwards he fibb’d a little) was this; That they being bred in the marshes themselves, and season’d to the place, did pretty well with it; but that they always went up into the hilly country, or to speak their own language into the uplands for a wife: That when they took the young lasses out of the wholesome and fresh air, they were healthy, fresh and clear, and well; but when they came out of their native air into the marshes among the fogs and damps, there they presently chang’d their complexion, got an ague or two, and seldom held it above half a year, or a year at most; and then, said he, we go to the uplands again, and fetch another; so that marrying of wives was reckon’d a kind of good farm to them: It is true, the fellow told this in a kind of drollery, and mirth; but the fact, for all that, is certainly true; and that they have abundance of wives by that very means: Nor is it less true, that the inhabitants in these places do not hold it out…”

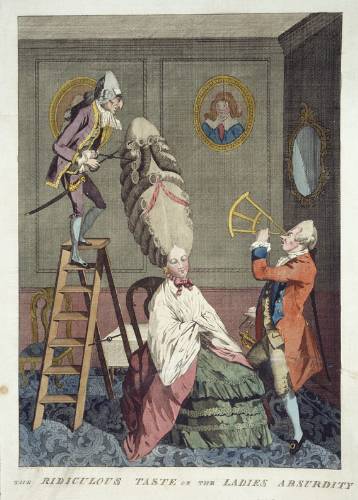

'' Representative of this genre is The Ridiculous Taste or the Ladies Absurdity of 1771. Here the hairdresser stands on a stepladder in order to reach the top of the structure. The husband, a naval officer, employs a quadrant, an instrument of maritime navigation, to take a fix on the pinnacle of his wife's head, which has, by implication, reached the stars.''

Defoe, the Whig, was a spy for the Tory Minister Harley for ten years. He wrote a newspaper for him. The two men, the hard drinking and deeply cunning aristocrat who kept his agent short of funds and who played him along, and the harassed but also deeply cunning adventurer, established a sort of friendship, based on their love of moderation. Defoe was secure. He lived in a comfortable house just outside London. And then Harley fell from power and the Whigs came in. A pause for some misadventures in the courts and then, like any purged Russian, Defoe once more ” confessed to past errors”, and became a secret agent and journalist for the Whigs.

Defoe’s life had been physically, not to say morally, exhausting. His career was only too well known. He was constantly attacked. In the eighteenth-century people had to endure attack without recourse to legal action for libel. In any event, at sixty, Defoe was politically a failure. This time, he was not at the point of disaster, but he was ”out” He was disillusioned, without political prospect. All he could do was write. But what? He looked around him, and having nothing else to write about, he simply wrote about his own people; not about policy and opinion, but about how people lived, what they thought and felt and said. The spur was his inborn confidence in his observation and his moral sense. Thus he went from pamphleteer to paperback writer.

And so the last act of impersonation suddely lifts Defoe out of the dim life of the arguing hack into the light of literature. He became Crusoe, Moll Flanders, Roxana, the saddler repo

g the Plague; he now became, as it were, the secret agent of the ordinary man and woman.To himself, to the educated classes, to the great writers of his time such as Pope, these books seemed like the low-class paperbacks intended for servant girls and written in their language. That is, unpolished, without idea or style, and ignoble in sensibility. The characters themselves were incapable of the higher feelings of the great dramas. They were mean. Defoe must have felt twinges of the shame of a talented man who gives up and takes to soap opera, who sells out to the worst of Hollywood or pulp magazines.

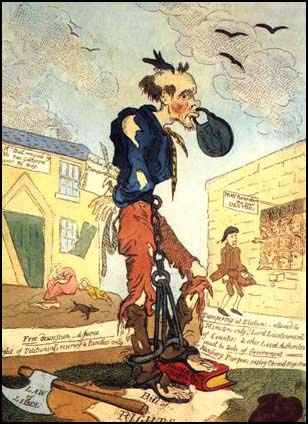

''Title: A Free Born Englishman! The Admiration of the World!!! and The Envy of Surrounding Nations Artist: George Cruikshank Date: 1819 Commentary: John Bull, a personification of England, in chains and gagged, stands on the Magna Charta and the Bill of Rights. And feels appropriate today as the liberties of Free Born Englishmen are gagged and enchained..''

Yet behind him he had his independence of mind, and, above all, his early good Dissenting education. Behind him also was a defiant sense of his own merits and of his own novelty as a person. Such were the untapped resources of his lifetime and such the vital excitability of this aging man that in five years, between 1719 and 1724, he ran off three masterpieces. The enormous success of Robinson Crusoe first of all astonished him. Then quickly, with his journalistic instinct, he claimed an extra significance for it; Robinson Crusoe was the allegorical biography of himself marooned on the desert island of Great Britain. As a shrewd and plausible afterthought, it was a substantiated allegory of a host of the pragmatic, capable, shrewd, enduring Defoes, winning the battle for survival in adversity, winning the battle for practicality, work, and natural cunning. It is an allegory of his king of Englishmen, whom Defoe thought no better than any other race, except in one thing; they keep their heads when things are going badly.

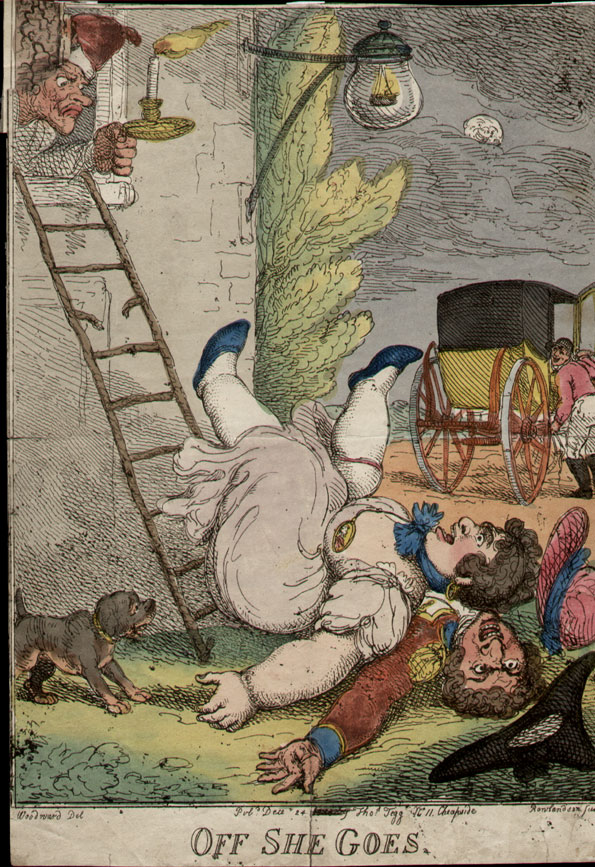

Rowlandson. T. Rowlandson. Off She Goes. Published December 24th (year obliterated), by Thos. Tegg No II (sic) Cheapside. 8¾ x 12¾. Original colour, trimmed to the image with the top left corner missing and crudely filled in and old folds. A fun Rowlandson image of an elopement. B. M. 11974. £50.

It is also an allegory for the Protestant mind with its high regard for conduct and its suspicion of sensibility and feeling. Crusoe represses all his spiritual alarms at his position as a man alone in the universe and in the eyes of God, for such preoccupations would lead to the paralysis of his conduct as an ingenious builder. The price he pays for this repression is nightmare; he is visited by the Devil. Crush the inner life and it returns in the form of monsters, as Goya noted in one of his more terrible fantasies. The dream of reason creates monsters.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS