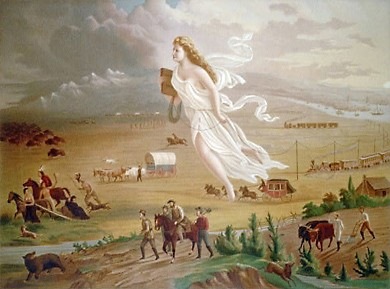

The concept of the Manifest Destiny has acquired a variety of meanings over the years, and its inherent ambiguity has been part of its power. ”Manifest Destiny was always a general notion rather than a specific policy. The term combined a belief in expansionism with other popular ideas of the era, including American exceptionalism, Romantic nationalism, and a belief in the natural superiority of what was then called the “Anglo-Saxon race”. While many writers focus primarily upon American expansionism when discussing Manifest Destiny, others see in the term a broader expression of a belief in America’s “mission” in the world, which has meant different things to different people over the years. This variety of possible meanings was summed up by Ernest Lee Tuveson, who wrote:

A vast complex of ideas, policies, and actions is comprehended under the phrase ‘Manifest Destiny’. They are not, as we should expect, all compatible, nor do they come from any one source.

.If there was no one among the defenders of America quite as great as Buffon was, or as Raynal thought he was, the general level of distinction was high. They were men who had moved out of the misty realms of speculation and into the tumultuous arena of history. Several of them played an active role in public affairs. They represented too, something of a cross section of western Europe. There was the exiled Jesuit, Father Francisco Clavijero, who had taken refuge in the exquisite Spanish College in Bologna, and there wrote his compendious ”History of Mexico” to refute Buffon and Raynal.

”He was also a brilliant writer and Jefferson was only one among many who thought that this was often a liability. “I must doubt whether in this instance he has not cherished error also, by lending her for the moment his vivid imagination and bewitching language.”5 Apart from showing a rather nice turn of phrase himself, Jefferson was here coming as close as he dared to calling Buffon a polished liar. Under a veneer of gentility, feelings were evidently extremely raw. Included in the ninth volume (1761) of Buffon’s great work, are three major conclusions: that the animals of the New World were lesser in size and numbers of species than those

of the Old World; that animals common to both continents were smaller in the New World; and that Old World animals transplanted to the New World fared poorly. At the same time “serpents” and insects abound.

Buffon’s data on the natural history of the New World (which he never visited personally) were assembled from the writings of others scholars and from direct examination of the specimens they brought home. Like so many, perhaps nearly all, scholars before him and since, his presentation was colored by prior ideas about the “why” of American nature.( Keith S. Thomson )

At the least, Buffon never wrote that degeneration would also affect transplanted Europeans. Indeed, he expressed optimism that Europeans would transform the New World and make it extremely hospitable and productive . However, some other European intellectuals, most notably the abbe Raynal, extended Buffon’s theory of American Degeneracy to include white Americans with an ”afflicting picture” of man in the New World; and these brazen an inflammatory allegations were swallowed whole by erudite, armchair thinkers such as Dr. William Robertson. According to Raynal,” transplanted Europeans would continue to be plagued by the inimical continent and that they should never expect genius and so never to be disappointed. In his 1770 publication, Histoire philosophique et politique des deux Indes (Philosophical and Political History of the Two Indies), the abbe Raynal wrote:

“One must be astonished that America has not yet produced one good poet, one able mathematician, on man of genius in a single art or a single science.”

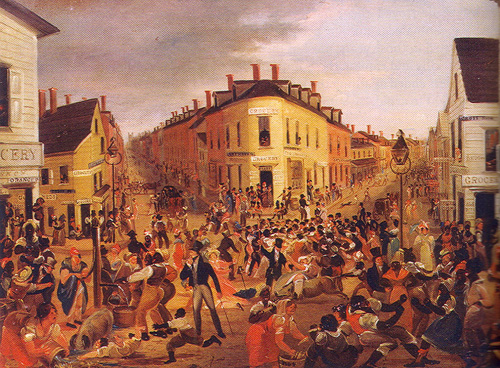

''This oil painting shows a scene set in the 1750s during the British, French and Indian War in America: General Sir William Johnson is shown stopping a Native American warrior from taking the scalp of a French soldier. Benjamin West (1738 to 1820) was an American, born in Pennsylvania, who studied painting in Italy before settling in London in 176

e is renowned for his portraits as well as his paintings of historical events.''From Italy, too, came the romantic Philip Mazzei, one of those familiar eighteenth-century figures flitting from career to career and from country to country; a physician in Smyrna, a wine merchant in London, a farmer and a soldier in Jefferson’s Virginia, a diplomat in Poland and Russia, a historian and a philosopher, trying his hand at half a dozen tasks and not doing any of them very well, but full of enthusiasm and good-will. Jefferson put him up to writing a Defense of America against the canards of Raynal, and while Mazzei was at it, he covered the whole ground of American history and economy in three volumes of his own and a forth by none other than the Marquis de Condorcet.But, all these justifications and rationalizations were peppered with the messianic fervor that fused the notion of materialism and individuality. Though persuasive and sophisticated, and sometimes theatrical, they were antipodal to the First Nation conception of land and our relationship to it. Though inspiring to settlers, this uninhibited fermentation was in he main, garish, corrupting and fatuous:

”The conflict was centered on the concept of land ownership. This put the native Indian nations (first nations) and the new immigrants at odds with each other. Most of these Indian nations viewed themselves as guardians of the land and its animal resources, not owners of it. This is in direct conflict with the notion of the European settlers who viewed land ownership as individual rights, not joint stewardship. In addition, the new American nation developed a concept of ‘Manifest Destiny’ which viewed all the lands in North America as the birthright of this American nation.” ( www.boerner.net)

There was the Mennonite preacher Adrian van der Kemp in Leyden. Van der Kemp had made the aquaintance of Minister John Adams and published a collection of American state papers; tried for a mixture of heresy and subversion, he was acquitted, joined the patriot ranks in the abortive revolution of 1787, and when a Prussian army crushed that heroic uprising, fled to the American wilderness, where he lived in Aracadian simplicity on the shores of Lake Oneida.

George Catlin Scalp Dance, Mouth of the Teton River, 1835–37 Western Sioux/Lakota Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr.

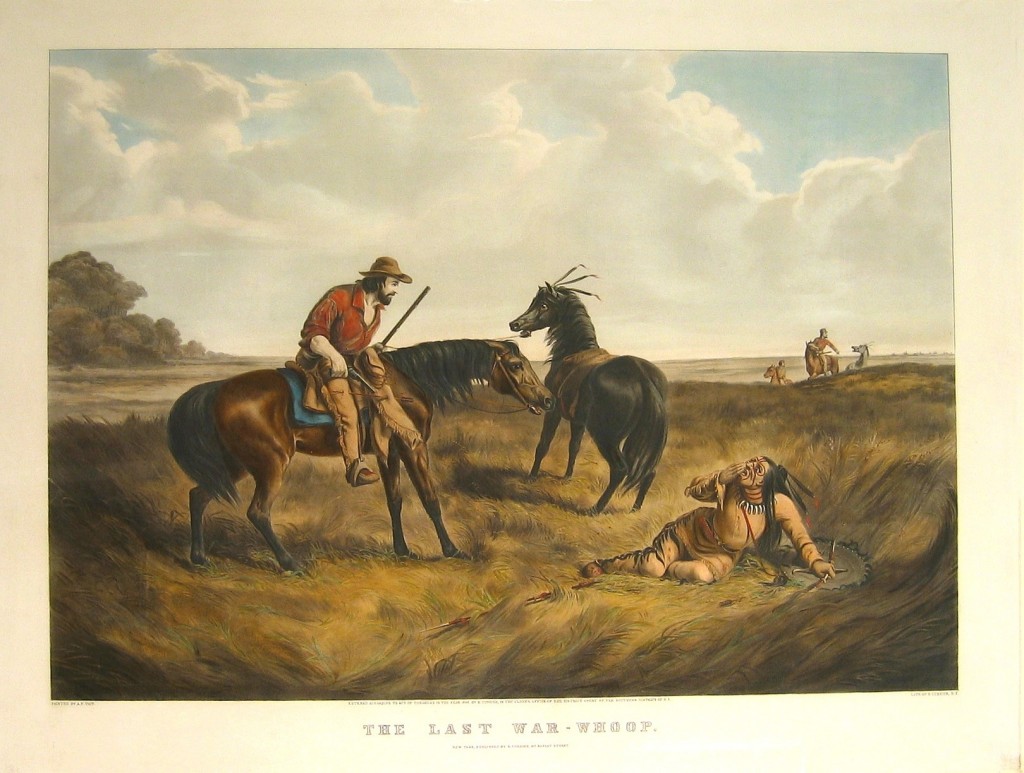

“We did not ask you white men to come here. The Great Spirit gave us this country as a home. You had yours. We did not interfere with you. The Great Spirit gave us plenty of land to live on, and buffalo, deer, antelope and other game. But you have come here, you are taking my land from me, you are killing off our game, so it is hard for us to live.

Now, you tell us to work for a living, but the Great Spirit did not make us to work, but to live by hunting. You white men can work if you want to. We do not interfere with you, and again you say why do you not become civilized? We do not want your civilization! We would live as our fathers did, and their fathers before them.”

— Chief “Crazy Horse,” Oglala Lakota

As the French, had, in a sense, launched the whole controversy, it was proper they should now conclude it. None wrote with greater authority than the Marquis de Chastellux. A soldier, an economist, and a philosopher, he could discourse not only on great questions of economy and philosophy but on the union of poetry and of music, and his inaugural address as a member of the Academy was on taste. He was above all, an expert on happiness. He had written two volumes on the subject and made it irresistibly clear that the present age was the veritable golden age, and he proved his devotion to his theme by providing ”Romeo and Juliet” with a happy ending. He had been a major general under Rochambeau and had cut a great figure in the French Expeditionary Forces at Yorktown.

All this went into the volumes of his ”Travels in North America” which described the American society as the most enviable, at once pastoral and sophisticated. The pastoral note was insistent and pervasive, but clearly what pleased the Marquis was the sophistication.He traversed the virgin forest, and what delighted him was a girl at a wayside inn ”whom Greuze would have been happy to have taken for a model” and the discovery that his landlord read Newton’s ”Principia”. He rejoiced in the strudy independence of the American farmer, but he was happiest in the company of American philosophers, like Bishop Madison of Virginia or Thomas Jefferson, and though he pronounced the customary warning against luxury, it was no rural Utopia that he foresaw but a nation whose trade and cities and wealth would in time create a flourishing civilization.

”The invention and reinvention of America continue to our day, and so does the argument that opening up AMERICA was a bad idea. No less a sage than Sigmund Freud remarked earlier in this century, “America is a mistake; a gigantic mistake, it is true, but none the less a mistake.” Whether the discovery was a curse or a blessing was a favorite topic for debate at the Oxford Union between the wars. The Columbus quincentennial charges the old argument with new intensity. But the terms of the debate, whether in the 1770s or in the 1990s, are inherently defective. Abbe Raynal’s question implies what few debaters could actually believe: that there was some alternative to Europe’s discovery of AMERICA.” ( Arthur Schlesinger Jr. )

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

powerful poem and song by trudell thanks dave!

thanks, I think he is quite an authentic. His first album is hard to find, but is really outstanding. produced by Jackson Browne.