The British eighteenth century used to be presented as the serene aftermath of the spectacular disruptions of the seventeenth century or as the quietly corrupt old regime against which a modernizing nineteenth century set itself. Both interpretations seriously underplayed the eighteenth century’s characteristic energy and dynamism. Whilst the traditional and conventional view does locate Britain’s ‘rise to greatness’ in this period, that interpretation was rendered strictly as a military and or imperial accomplishment achieved within a narrative of high oligarchical politics. Its likely, that its more enduring and important achievement lies in the domain of cultural perspective. A Cultural evolution that took a quantum hop into a new array of new subjects for investigation, from the body, sexuality and gender through habits of work and leisure to the institutions that produced and reproduced human experiences.

''Hogarth’s series The Rake’s Progress tours the shadowy corners of a vicious life—vicious in its eighteenth-century meaning of being addicted to vice—including this scene at the gaming tables, where the young rake seems possessed by a gambling fever.''

It was the first great age of conspicuous consumption.An age just prior to the mistrust and influence of what was called ”vagabond wealth”; wealth not tied to the land and tradition and created by the nascent industrial and commercial class. Colossal mansions spread out over acres and acres of landscaped countryside. Secure in their wealth, confident in their position, indulged by their countrymen, the aristocrats of eighteenth-century Georgian England did their thing, and in doing it , invented and established our present ideals of civilized living. English wealth from at home and the colonies led to the Grand Tour, a frequentation of Italy and a rediscovery of the Renaissance through art and antiquities of Florence, Venice and Rome in particular; home comforts and a sparkling social life acquired new meanings for the British, who began to identify and admire a civilization which had been based upon mercantile wealth and liberty.

English: Thomas Rowlandson, brother satirist to Hogarth, painted his version of a gaming den in The Hazard Room. On the walls is a bouquet of gambler’s delights: boxing, horse racing, the odds of the day, and the patron saint of card games, Edmond Hoyle. Date 1 January 1792

In an economic context, commerce is central to an understanding of the cultural dynamics of the eighteenth century; the commercialization of leisure and the expansion of material consumption as a domain of personal expression are themes that were particularly prevalent. Commerce, however, also referred to social forms of human interaction. This sort of commerce – its idealization in theories of conversation, sociability and politeness in a culture of association – helped to configure many practices and institutions of culture.

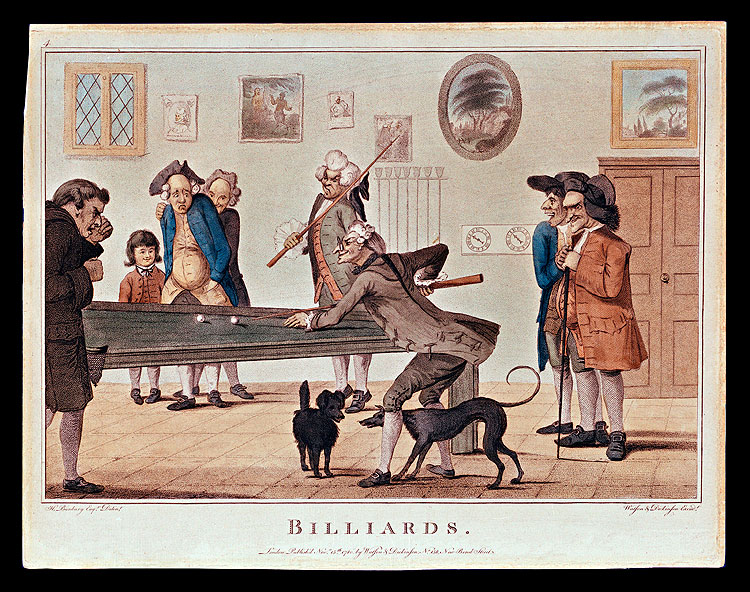

horse and foot races were sports of choice for improving a person's leisure hours. Indoors, a game of cards or billiards, seen here in an eighteenth-century English print by Henry Bunbury, prompted friendly competition at the local tavern.

Art and culture is inextricably bound with the notions of identity as well . This was a great era of appropriating culture; in this case from Italy, and to a lesser extent from France, and fashioning a national cultural identity; identity as a source of solidarity in a society, but also a matter of contestation. Cultural politics in action and representation being an expression of the desire for and clash over, power. A cultural history that shaped understandings of : politeness and impoliteness; taste and vulgarity; the patrician and the plebeian; sociability and solitude; ancients and moderns; reason, sensibility and sentiment; classicism and romanticism; public and private; sociability and domesticity; virtue, luxury and commerce; professionalism and amateurism; metropolitanism and provincialism; culture and nature.

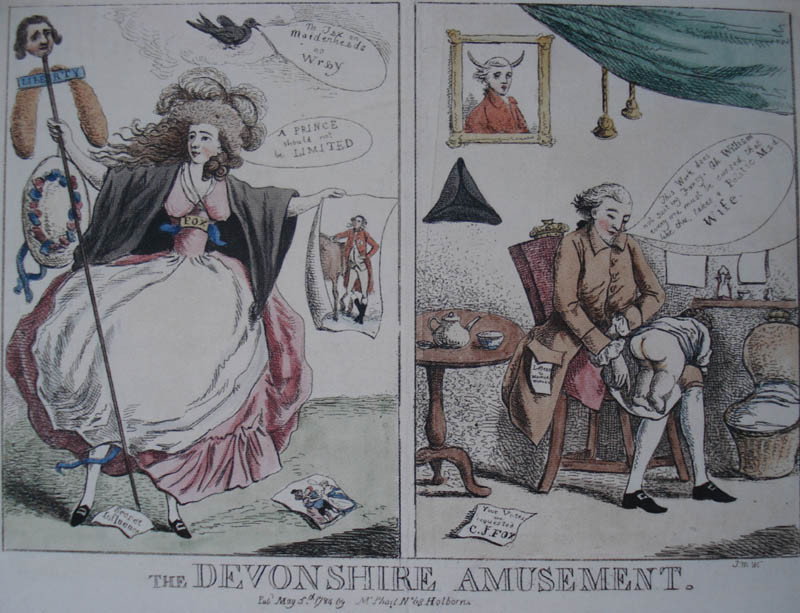

''The above image is one of my favorite depictions of her Grace. It is a satirical image from 1784, which happened to be a very big year in the Duchess' life. Not only did she have her first child after years of painful miscarriages, but she also became notorious for her part in the 1784 Westminster elections. In fact, this seemed to be the thing she became the most known for, besides of course being a leader of fashion. She became the first woman to canvass for a political leader, hers being Charles James Fox. The image shows Georgiana on the left brandishing a staff with the head of Fox on it, identifiable by the fox tails. She holds in her other hand an image of the Prince of Wales, another Whig figurehead. In the right panel we see her cuckolded husband tending to their child.''

”Man is the crown of God’s creation and as such he possesses many good attributes. These are best cultivated when man is granted a measure of liberty. But man is also a fallen creature, beset by proclivities that are harmful to himself and to society. Among these are overweening pride, the thirst for power, the love of luxury and of adulation, and all manner of other dark impulses”….

…. Life was a perpetual succession of enthusiasms. Wherever these wealthy gentry went, they gambled. It was the national mania, but the nobility led the way. Their great passion was horse racing, and they organized the Jockey Club, formalized the rules of racing, and set up an elaborate racing calendar so that great races never conflicted in date. And, of course, they established the racing classics; the Derby was named after the Earl of Derby, an obsessed racing man, and the St.Leger at Doncaster was named after his northern counterpart, Colonel St. Leger.

But horses assuaged only a part of their passion for gambling. In London, the young noblemen took over coffee-houses and turned them into private clubs whose main business was gambling at cards. Charles James Fox, the distinguished Whig politician and hero of the Westminster public, gambled away two fortunes at Brooks’s before he reached middle age. Indeed, before he was sixteen, he and his elder brother had got throug

out $50,000 apiece in three days. The earl of Sandwich found it impossible to drag himself away from the Faro tables even for supper, so he dined there on two slices of bread stuffed with meat. Women gambled as passionately as men. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, beautiful, elegant and wanton, had no more self-control at cards than she had at love. She runed herself beyond repair by her extravagant bets.

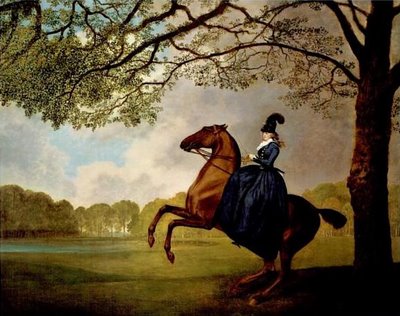

Stubbs. Eclipse. 1770. '' It was at this race on May 3, 1769 that the flamboyant Captain Denis O'Kelly made his bet in the form of the quip, "Eclipse first, the rest nowhere." In 1769, a horse that was more than 240 yards behind the winner was said to be "distanced", or nowhere. O'Kelley won his bet and became a part owner of Eclipse. Eclipse won 18 races in his career without ever being whipped or spurred. Eclipse retired to stud and sired three of the first five Derby winners including the noted Pot-8-O's. Eclipse's many distinguished descendants are the reason for the predominance of his great-great-grandfather the Darley Arabian's line over the lines of the other two Foundation stallions. 80 percent of all Thoroughbreds today can trace their ancestry back to Eclipse. ''

Cards and horses were major addictives, but so were prize fighting, cock fighting, and above all, cricket. Cricket developed its elaborate rules in the eighteenth century and became popular because it provided such a rich and complex situation for gambling. One could gamble not only on the result but also on an almost infinite number of chances within the game. If the ladies and gentlemen grew bored with the usual round of horses, cards and games, they could and did gamble on anything. The few betting books that survive from the eighteenth century betray better than any other source the feckless abandon of young aristocrats who might bet on the fertility of a duchess, or a raindrop running down a pane of glass, or, perhaps more startling of all, whether, before the year was out, Lord Cholmondeley would copulate a thousand feet above London in one of the new balloons.

Zoffany. The Bradshaw Family. ''...art history and visual culture more fully with the visceral spaces of gendered and racialized subjectivities, by focusing on an involuntary bodily performance, the blush. Towards the end of the eighteenth century British artists in particular represented their female sitters with pale, white skin and strikingly flushed cheeks. What did the blush as a corporeal eruption mean in a culture where the circulation and mixing of blood was a cause of great anxiety? The essay suggests that far from being just a marker of beauty or virtue, blushing cheeks of the so-called British Fair also came to signal racially. The gendered concept of whiteness that became legible in the depiction of European woman's blushing skin will here be seen as both an expression of anxieties about racial purity and a means by which the English formulated ideals of femininity and nationhood. ''

But gambling was not all extravagance and loss. In the 1780′s the young bloods developed a passion for racing each other in their carriages from London to Brighton. Like present Formula racing, they and their carriage builders poured ingenuity and money into creating flimsy but extremely fast phaetons, which they drove with exceptional speed and skill. With Tommy Onslow, who once won twenty-five guineas from the Prince Regent by driving his phaeton and four at a gallop through two narrow gateways twenty-five times without touching them, Sir John and Lady Lade were aces at this sport.

Lady Lade swore like a fishwife, and in fact Sir John first made her acquaintance in a brothel in one of those rare occasions when he left his stables. Bankrupted by his passion for gambling, he finished his life happily enough as a coachman on the London to Brighton run, which he had done much to improve. The racing phaeton , like the racing motorcar, brought great technical improvement both to vehicles and to roads.

''“Vincent Lunardi used a Union Jack design on all his later balloons, and attracted increasingly large crowds to his launches. In 1785 he took his displays as far north as Edinburgh. But he often had trouble with crowd control, and rowdy disturbances became an important element in the balloon craze. It was dangerous to delay departure beyond the promised hour, even if the balloon was not sufficiently inflated or the wind was adverse. When the newspapers reported a successful launch, it often simply meant that the balloon had lifted off on time and no one in the crowd had been killed.” “Lunardi’s reputation was badly damaged the following year, when on 23 August at Newcastle a young man, Ralph Heron, was caught in one of the restraining ropes, lifted some hundred feet into the air, and then fell to his death.''

The social theory of the time was best exemplified by Edmund Burke; with the basic idea being an unparalleled degree of social, religious and economic freedom with the caveat that the established institutions of government and the existing structures of English civilization are not to be toppled. Burke lived in a time of enormous change which brought in its wake decades of political ferment and, finally, the explosion of the French Revolution. An astute observer of human nature, he was impelled by events to analyze the structures of the societies that civilized man had built and to look for common patterns in history. He hoped thereby to assist his own country, Great Britain, in averting the disaster that had befallen the French and, at the same time, to help his countrymen appreciate better those things that allow men to enjoy a measure of personal liberty and contentment within a framework of political and social order. The radicals of the French Revolution proposed fundamentally to refashion life in accordance with their new ideology. Burke grasped the mortal danger in such experimentation and pledged his considerable gifts in trying to halt that Gadarene rush to calamity.

”Burke is most remembered as the chief philosophical opponent of the ideology that gave birth to and nurtured the French Revolution, and of that Revolution itself. It is especially in the last of his writings, published in the 1790s near the end of his life, that the major elements of his political philosophy were brought together. Less discerning men, some even among the British aristocracy, had been swept up by the wild optimism surrounding the collapse of the _Ancien Régime_ in France. Burke saw matters more clearly. Writing with a passionate eloquence born of crisis, he demonstrated how the upheaval in France threatened to undermine the whole of the foundation of the order of life as it had been accepted among civilized men for over a thousand years and threatened the whole of Christendom, including his own country.”

Stubbs. ''I imagine the marriage was actually a fun one. The two were so similar in their tastes. When John's friend, the Prince took interest in Letitia, the two seemed to enjoy the game of his pursuit (The Prince even commissioned Stubbs to paint her portrait). Unfortunately, they also had similar spending habits and were commonly in financial turmoil. Letitia relished her new place among the aristocracy while they, in turn, found her a bit course. Her casual cursing was overwhelming to many and began the phrase, "he swears like Letty Lade!" Her carnal past also was a hot topic and she was said to, "withstand the fiercest assault and renew the charge with renovated ardour, even when her victim sinks dropping and crestfallen before her," and that she never "turned her back against the most vigorous assailant."

Burke’s view also prevailed in literature as well. In the eighteenth century the novel had not yet been understood as a vehicle for the real reformist, except perhaps in Godwin’s use of it in Caleb Williams. The failings of social institutions are seen as a kind of cumulative failing of corrupted individuals, like Justice Thrasher in Amelia, who in their turn produce more corruption. The depredations of individuals upon one another produce social evils. Thus to improve society, the heart and mind of the individual must be reformed, but the structure remains. Brooke and Day criticize the education of aristocrats rather than the class structure itself.

In Nature and Art Inchbald reserves her primary anger for William, the powerful and callous man who destroys Hannah by willfully seducing her; only secondarily does she lament the support his individual action takes from the structures of society. Like Godwin and Bage, she sees the need for societal safeguards to protect the individual from abuse, but the abuse itself stems first from distorted relationships among men. Even Holcroft, whose Hugh Trevor comes very close to attacking the institutions themselves, stops short and attacks instead individual corrupted members such as the bishop and Lord Idford. Only Godwin carries through the logical premises of his novel to indict directly not only corrupt individuals but the institutions that corrupted them. In Caleb Williams the tyranny of society is so oppressive that nothing can save Caleb or Falkland.

''Joseph Wright is notable for his use of Chiaroscuro effect, which emphasises the contrast of light and dark, and for his paintings of candle-lit subjects. His paintings of the birth of science out of alchemy, often based on the meetings of the Lunar Society, a group of very influential scientists and industrialists living in the English Midlands, are a significant record of the struggle of science against religious values in the period known as the Age of Enlightenment.''

The abuse of power is a common theme in the eighteenth century novels of protest and so too is the misuse of power— the first being deliberate, the second in error. Certain scholars have remarked on the depictions of arbitrary power that are so frequent in these novels, but it has not been noted that many of the novels attribute the misuse of power to misguidance rather than to malice. Brooke, Day, and Inchbald suggest that aristocrats are badly educated and that an education in benevolence and usefulness for them would create a better society.

Godwin, in one context, attributes Falkland’s character to his education in an outdated chivalry. Education is seen as a tremendously powerful force, and although several of these novelists complain that it is misused in many cases, especially with upper class children, they also suggest that society has an extraordinary potential for good precisely because of the promise that a socially healthy education holds out. In Anna St. Ives Holcroft insists that it is possible to “contribute to the great, the universal cause . . . the general perfection of mind.” While young William in Nature and Art is the unhappy product of his education, his cousin Henry is the wonderful human being his education should make him.

Joseph Wright. Brooke Boothby. ''Brooke Boothby, a Derbyshire landowner and intellectual. Boothby was involved in the thriving literary community of Lichfield in Staffordshire, the birthplace of Samuel Johnson. In 1766-7 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, prophet of the cult of nature, stayed in Staffordshire while in exile from France, and Boothby was part of the enlightened circles in which he was feted. In the late 1770s Boothby visited him in Paris and was presented with Rousseau's autobiography in manuscript in 1780 Boothby published, in Lichfield, the posthumous first French edition of the First Dialogue of Rousseau Juge de Jean Jacques.''

Belief in the power of education as a force for the improvement of society colors the protest, for it suggests that there is a relatively easy and likely cure for much of what is wrong. Brooke, Day, Inchbald, Holcroft (in Anna St. Ives), and Bage all imply that any man will choose goodness and productivity if he is enlightened to those goals, and a society of such enlightened men will be a juster society. Except for Caleb Williams, the various protests are made within this context. The prevailing spirit of these novels is that the failings of society, once they are exposed, will be ameliorated by rational men of good will.

The attack on arbitrary power is largely fueled by this expectation, for the notion of arbitrariness is antithetical to rationality. Arbitrary power is attacked in most of the better known novels. While government is left standing, and its continuity is not in question, the same cannot be said about the extent to which traditional relationships are questioned.

By the 1790s the assumption that parents have unlimited authority over their children merely by virtue of their parenthood is no longer accepted. Parents are to be judged by the same rules as everyone else. A stupid parent should not be respected; a tyrannical parent should not be obeyed. It is each person’s duty to become the most productive member of society he can be, and anything that interferes with that goal, a bad or misguided parent included, must be avoided. In these later novels, reason rather than custom is the ideal mover in human affairs, and so in Anna St. Ives for example, it is not acceptable to say, as Evelina does, that one must obey a father just because he is a father. One must obey only the dictates of one’s reason….

COMMENTS

COMMENTS