”Every human face is a hieroglyph which can be deciphered, indeed whose key we bear ready-made within us” ( Schopenhauer )

From the ancients onward, Europeans in particular have puzzled over the face, devising methods for interpreting its secret language. The classical science of physiognomics involved deciphering an individual nature by comparing his or her physical appearance to certain types of races or animals, the nature of which is assumed to be known.

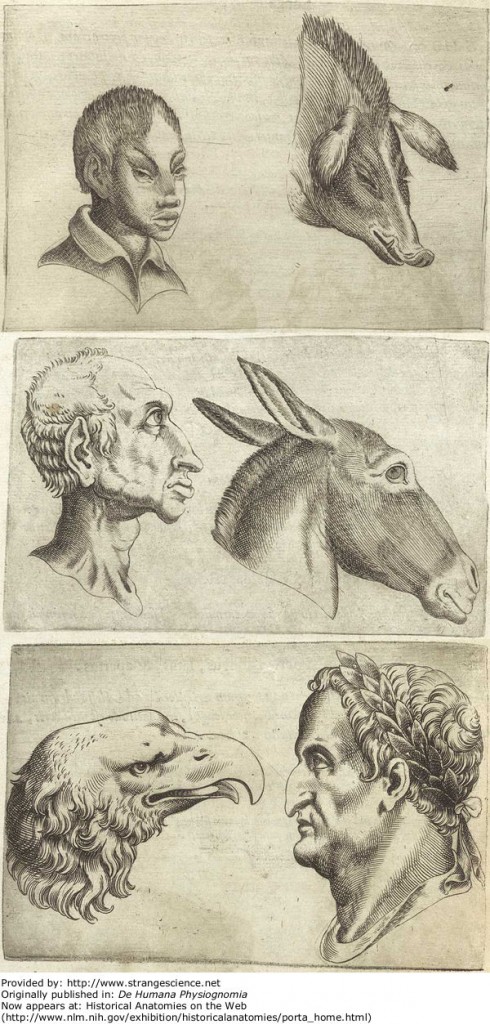

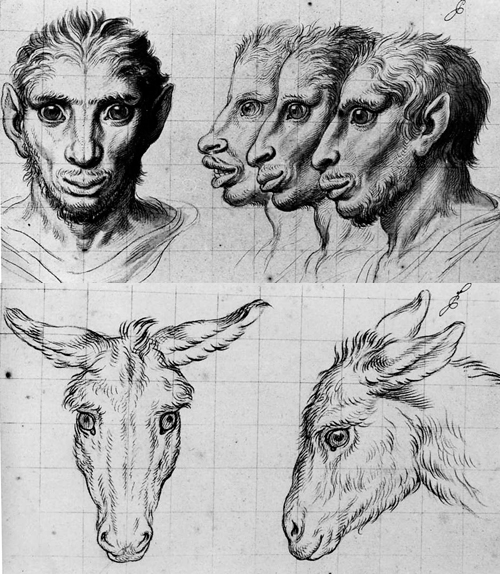

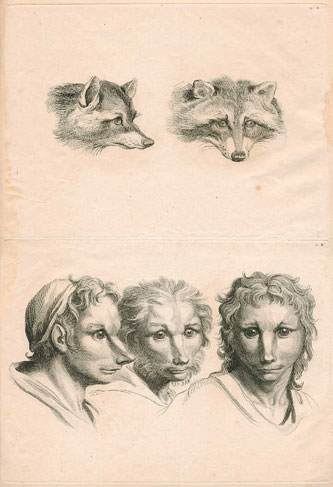

Year: 1586 Scientist: Giambattista Della Porta Originally published in: De Humana Physiognomia Now appears at: Historical Anatomies on the Web (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/porta_home.html) In his De Humana Physiognomia Libri IIII, Della Porta produced plenty of examples of human-animal similarities, some less noble than others. Della Porta also believed in the doctrine of signatures, that plants resembling certain body parts could cure what ailed them.

Reference to the face as a mirror to the soul are found in early Greek literature. The face was first conceived as a mirror of the soul by the ancients; and independent of body and soul in Aristotle,s theory. This notion of contiguity between body and soul underlines the use of physiognomics as a diagnostic tool; face as symbolic form.

Patricia Magli describes this as an ethical and passional similarity between all things. In this world view the notion of particular human types is divined by detecting resemblances between human and other forms, including animals. Magli called this ”reversed mirrors” in which fixed as emblematic image, animals act as reversed mirrors throughh which it is possible to recognize the passions, vices and virtues of man.

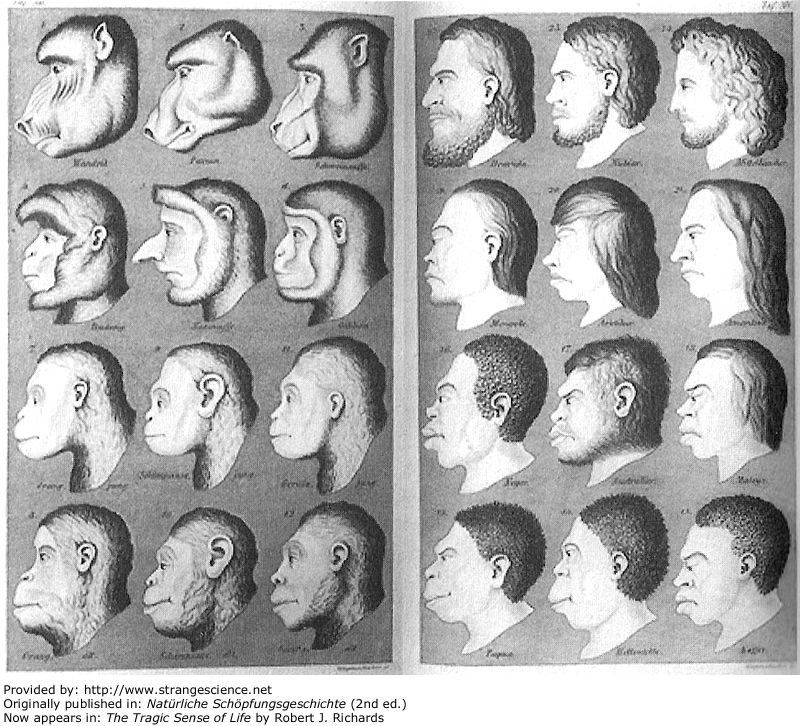

''"Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud" by Nick Hopwood in Isis June 2006 issue Reminiscent of Charles White's 1799 diagram, this illustration pointed out the affinity between the "lowest humans" and "highest apes." The heads pictured here were supposed to represent — from best to worst, so to speak — Indo-German, Chinese, Fuegian, Australian Negro, African Negro, Tasmanian, gorilla, chimpanzee, orang, gibbon, proboscis monkey, and mandrill. An interesting shift from White's diagram was that the best of the best was no longer Grecian but German. In fairness to Haeckel, he didn't like this illustration much (his publisher apparently did), but an expanded version appeared in the second edition of his book. Haeckel was, to say the least, confident of the superiority of the white race, as were many of his contemporaries. But at least one scientist, Michael Foster described the illustration in Haeckel's second book as "at once absurdly horrible and theatrically grotesque, without any redeeming feature either artistic or scientific."

Magli’s notion of reversed mirrors shows how from its origins physiognomics is underlined by a contradictory relation to others. As she suggests, the human desire to seek resemblances allows for infinite possibilities of otherness that lead to highly ambiguous forms forms assuming overwhelming importance such as della Porta’s character masks: Goat-man, Lion-Man, Monkey-Man and so on. At the same time, the ”science” of physiognomics is a powerful means of repressing otherness by attaching moral significance to all things and thus limiting meaning produced by the logic of similarity.

The Church also integrated this view into iconic frontispiece images of saints, including portraits of would-be saints. These images, together with accompanying texts, formed part of the manufacturing of the new faces of sanctity of Catholic Reform. Frontispiece images of saints operated less as passive adornment of the lives they accompany, than as re-routings of the authority of sanctity in relation to specific-interest groups within each community. Thus, frontispiece depictions of saints participated in the staging of a new image; portrait frontispieces and other iconography of saints and would-be saints would depart significantly from the textual lives, which emphasize pain-filled piety rather than ecstatic transports. They thus evoked both for ecclesiastical authorities overseeing the processes of canonization and for their devout readers an ideal of modern female and male religious devotion not as transgressive and miraculous, but as respectable and everyday.

'' according to which he came from a land of cannibals and dog-headed peoples. The Greek tradition came to interpret this passage absolutely literally, and this is why Byzantine icons often depicted St. Christopher with a dog's head. In time, of course, this led to a reaction against St. Christopher. The Latin tradition developed along different lines, however, since early Latin translations did not always render a literal translation of the original Greek term "dog-headed" (kunokephalos), and some seem to have translated it as "dog-like" (canineus). This was amended to read "Canaanite" (Cananeus) as time progressed since it was obvious that he could not really have been "dog-like".7 It is important at this point to emphasize that the description of Christopher as from the land of the dog-headed has absolutely nothing to do with the Egyptian cult of the jackal-headed god Anubis.8 The real explanation is rather more prosaic. In brief, the civilised inhabitants of the Greco-Roman world had long been accustomed to describe those who lived on the edge of their world and beyond as the strange inhabitants of stranger lands, cannibals, dog-headed peoples and worse.''

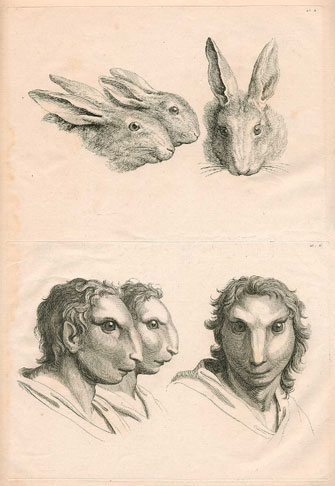

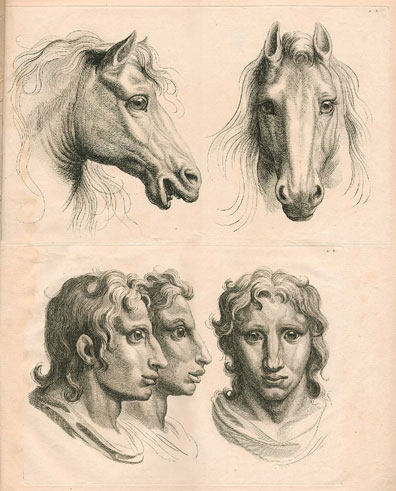

Over the centuries however, of all the savants, pseudo-scientists, charlatans and wacko’s who addressed themselves to the subject, none produced a more attractive commentary upon manly-beasts or beasty men than a seventeenth century frenchman named Chales Le Brun. He was no intellectual genius, but he did draw better; animals devastatingly juxtaposed with with human faces that mightily resemble them. At their best the caricatures are quite convincing, though ultimately the bizarre and grotesque exaggerations of a pathological misanthrope.

Unfortunately, he was the leading painter and art director of Louis XIV and ran the Royal Academy on authoritarian classical lines. His study of physiognomy was part of his broader and equally well illustrated dissertation on pathognomy. That is, feeling that rise from the soul cause visible changes in the body. A year after his death, fragments began to be published, to general satisfaction or lack thereof, though his student and biographer, Monsieur Nivelon asserted , &#

;far more than the standard effort to attach odious passions to odious physiques”.

The narrow forehead and hooked noses of the rabbit-men were signs of lesser character in his ''system''; the rabbit people look undeniably stupid. By contrast, the profiles of the horse and his lookalike suggest a nature that is impetuous, noble and proud, at least to he suggestible and the horse loving.

Le Brun began with the study of man, exhibiting neoclassic weakness for ancient Greece and the classic value of harmony. Naturally, the perfect human type, according to Le Brun, is represented by classical renderings of the Gods. Conveniently, Le Brun found that such statues of Jupiter for example, had strong noses, large eyes, and a wide forehead framed by thick hair as ”an intentional imitation of the mane and other attributes of the king of beasts”. What was good enough for the Greeks was good enough for Le Brun. Many of these physical features became part of a list of ”signes superieurs” in men and beasts.

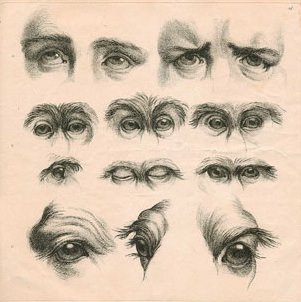

Le Brun. comparison of eyes. Dissertation sur un Traité de Charles Lebrun concernant le Rapport de la Physionomie Humaine avec Celle des Animaux Paris, Chalcographie du Musée Napoléon, 1806

But Le Brun, as well as being a classicist, was a Christian and a seventeenth-century intellectual. He wanted to present a complete scientific system, one that did not depend entirely upon pagan example or random observation. On the scientific side he had readily available Descartes celebrated theory that the seat of the soul is the pineal gland located at the center of the brain just behind the forehead. Combining that, with to him, unquestioned fact that heaven, source of all wisdom, intelligence and virtue, lies above us; Le Brun worked out a system for calculating character by the position of the eyes of the face.

Men have virtue, he concluded, in proportion to how easily their eyes may be turned upward toward heaven, and the pineal gland. Nivelon tells us that Le Brun made numerous studies of human and animal eyes and brows, among them those of the monkey, camel, wolf, fox, bear, lynx, cat, he-goat, ram and sheep. Of them all, he concluded, only man is capable of directing his glances toward heaven without having to raise his head.

Thereafter, the measurement of virtue was simplicity itself. If the inside corner of a man’s eyes were higher than the outside corner, the man would be ”moved by noble and generous passions, destined to merit immortality”. But woe to the man whose eyes were too deeply set in his face, as were the emperor Nero’s , or worse, whose eyes slanted down toward the center, as they do in Le Brun’s portrait of boar and donkey man. These men would be prey to passions and motives that were ”honteuses, meprisables, et atroces” The index of how noble a man was, or how ”shameful, despicable and atrocious” was the angle formed by the eyes in relation to a horizontal line drawn from the outer corner of one eye to the outer corner of the other. Another significant line could be drawn from the outer corner of each eye toward the forehead at an angle determined by the upper curve of the eye.

Le Brun himself, as portrayed in the grand style by the sculptor Antoine Coysevox, looks alarmingly like some of his sketches, particualrly, the fox-man; his syatem of facial measurement, applied to the fox would have revealed a highly developed, though misguided intelligence.

Le Brun’s original work was divided into four categories: facial studies of the portraits of ancient notables to show the connections between their features and character, such as an aquiline nose turned out to be proof of courage; parallel portraits of men and beasts together; studies of eyes in men and beasts; and last, an anatomical analysis. Most of Le Brun’s drawing that remain in the form of engravings and lithographs, are from the second and third category. Of these, the human-animal comparisons are the best. In some Le Brun works up detailed portraits ; in others he overlays his human and animal profiles and front views with a whole geometry of triangles, parallel lines, and points that show different characteristics in men and beasts.

”There is no doubt that Charles Darwin was sceptical about the claims of physiognomy with regard to expression and emotion. Nonetheless, it is interesting that his study of expression makes a number of contradictory claims about the possibility and plausibility of conducting a scientific analysis of expression. Darwin’s oft-neglected work, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), was self-consciously presented as the cornerstone of his evolutionary theory — the means of demonstrating once and for all that man was not a separate and divinely created species but continuous with other species. An evolutionary account of expression was not concerned with teleological explanations of physical attributes; rather, it was directed towards finding a means of understanding the process through which expressions are acquired. The result was a study of expression that tried to identify specific mental and emotional states as well as their corresponding expressions (by concentrating on their motor activity), and then map their common descent through groups of related organisms. If this could be done, then human feelings like love, anger, fear, and grief could be treated as habits and shown to have clearly recognizable parallels, perhaps even origins, in the animal world.

The rise and triumph of these inner, scientific rationales for the expression of the emotions placed the study of expression on new ground. Indeed, the evolutionary explanation of expression given by Darwin (and taken to its logical, albeit odious, conclusion by Francis Galton, father of eugenics) is both the long-term outcome of physiognomical teachings and the reason for their dissolution. As we reflect on the impact of physiognomy, there is much to suggest that its demise is no bad thing.” ( Lucy Hartley )

COMMENTS

COMMENTS