Hans Memling’s ”The Seven Joys of Mary” is a pageant as much as a painting, a dramatization of holy events in a landscape that might accommodate the revelry of a midsummer eve. Exactly what is going on is hard to sort out at first glance. Surely it is Twelfth-night , for what can only be the Magi and the Holy Family are in the forefront of the action. Yet it must be Christmas Day as well, for to the left of the throng at center is a radiant Nativity scene, observed through a window by two men in black. What is the city that sits in mid landscape like a crown? Jerusalem, no doubt, for such a skyline can only denote the home of kings.

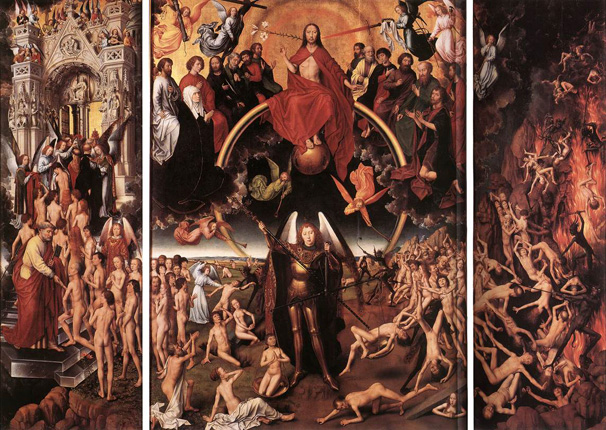

A painting with complex iconography: Hans Memling's so-called Seven Joys of the Virgin - in fact this is a later title for a Life of the Virgin cycle on a single panel. Altogether 25 scenes, not all involving the Virgin, are depicted. 1480, Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

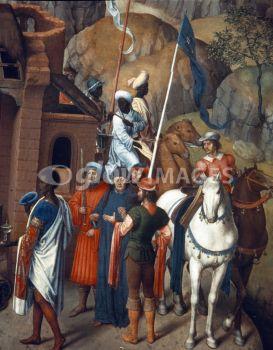

It quickly becomes apparent that the space we see is not realistic, nor are the events simultaneous. The chief event depicted is the journey of the Three Wise Men. It begins in the farthermost distance, with each man perched on his respective mountaintop observing a star. The three join forces in the foothills; then they appear inside the walls of Jerusalem with King Herod and continue to Bethlehem, where they play their scene and depart, winding their way down to the sea to embark for home. But there is much else besides the Magi.

We see a flight into Egypt, a resurrected Christ, two annunciations, one ascension, one assumption, and assorted other miracles, all of them mingled with such everyday sights as horses drinking from a pool, boatmen plying a river, birds on the wing. No satisfactory title is known for this felicitous creation by the fifteenth-century master Hans Memling. ”The Seven Joys of Mary” is traditional if inaccurate, for Mary’s seven joys are specified by church tradition, and Memling has omitted a few.

Memling finished the painting in 1480, and it was hung in the Chapel of the Tanners in Notre-Dame of Bruges. it was commissioned by a wealthy member of the Tanners’ Guild, Peter Bultinc, who is portrayed as the foremost of the two observers at the Nativity. Behind him stands his son; his wife, oddly enough, has been relegated to the opposite side of the painting and given a chained monkey for a companion. No one knows what Memling had in mind here, but monkey’s were often used as a symbol of stinginess; perhaps Dame Bultinc was reluctant to spend whatever it cost to have Memling immortalize her.

Hans Memling is one of the school of great masters known as Flemish primitives. They are hardly primitive, except in the sense of being the first to paint with oils, and Memling himself was not even Flemish, though he did spend his productive years in Bruges. Flanders was at the time part of the duchy of Burgundy, the powerful medieval state that for a century stood between france and the Germanic kingdoms. Memling died in 1494, as Burgundy was crumbling and the high culture of medieval Flanders along with it.

Some time during this almost total eclipse the people of Bruges invented a yarn about Memling that made him out to be a profligate and libertine who had soldiered for Charles the Bold. This Charles, the last of Burgundy’s independent dukes was brutally slain in battle near Nancy in 1477, and it was said that Memling, wounded, had made his way from Nancy to Bruges and fainted on the doorstep of the Hopital Saint-Jean. The good sisters took him in, and Memling recovered, reformed, and began to paint pious little pictures.

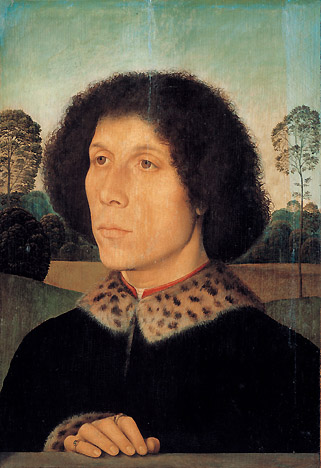

The truth, unearthed from the archives in Bruges, turned out to be rather less romantic. Memling was not Flemish but German and had arrived in Bruges not as a soldier, but as a master painter. Married, with three sons, he was listed as one of the 217 most heavily taxed burghers and he bought a substantial house. Since twenty-five portraits by him have survived, he was much sought sought after; and since most of his clients were business tycoons, we may conclude he had an international reputation.

All his works reveal one quality in common: a gentle serenity. Memling lived in a day when warfare was regarded as a godly calling and executions were a form of public entertainment; violence, as in our day, was endemic, and was nowhere more commonplace than art. Yet Memling had no stomach for painting martyrdoms.

In any case, “The Seven Joys of Mary” shows a landscape that is not realistic in the usual sense, neither is it totally imaginary. The hills, the boulders, the sea and setting sun, the winding roads, the carefully sectioned architecture, are all highly artificial inventions, but inventions possibly borrowed from another art form: the theatre. They function exactly as a stage set might in a certain kind of drama.

''The Passion cycle is enacted in this setting with the addition of the Resurrection and several of Christ's appearances to his followers, but without the Ascension. This is the first time that Memling applied the spatial narrative structure that he was later to use on two other occasions (Munich and Lübeck) to present a Gospel cycle. The narrative meanders symmetrically from the rear left to the foreground and through the principal scene in the middle, before culminating on the right, once again in the distance. Calvary is set somewhat apart as the principal scene in the background. Christ's various appearances after his Resurrection are not particularly significant in iconographical terms, and are probably included as visual links running into the landscape. The painting enabled believers to visit the Holy Places in and around Jerusalem in their imagination. It is a kind of spiritual model of the crusaders' journey.''

The story of the Magi was, quite literally, a drama, and the ”Play of the Three Kings”, given first in Latin and eventually in the vernacular, was among the most widely performed of all the medieval mystery plays. There is no direct proof that Memling ever saw such a play, yet there can be little question that he knew every byway of the Magi’s journey. By Memling’s day, this ancient legend had been brought to its most elaborate form , and with one or two exceptions he includes every twist and turn, every complication, that a thousand years of piety had managed to invent.

This venerable Christmas tale had about as much historical basis as, say, the story of King Arthur. But to explain how the tale was invented, and why Memling might have felt a special affection for it, one must go some distance back into the history of the world.

The painting is the central panel of a triptych, the left panel being the Carrying the Cross, the right panel the Resurrection, all in the Budapest Museum. The triptych is related to Memling's large altarpiece executed for the Cathedral of Lübeck representing the same scenes of Christ' Passion. It is assumed that an early sixteenth-century Bruges master combined elements of a lost Memling triptych with Memling's Lübeck altarpiece to produce this triptych.

From the beginning, Christianity borrowed from the religions it displaced. No element of Christian belief bears more witness to this than the story of the Magi: tribute bearers, kings from afar bending the knee to the new God, as captive royalty had always had to do. The only Gospel that mentions the Magi is that of Saint Matthew, who recount the magi coming from the East, guided by a star. The term Magi was seen by the Romans as denoting the Zoroastrian priests of Persia and the Near East. Zoroastrianism was an ancient fire religion, the priestly duties for which included the tending of a sacred flame, usually upon a mountaintop. These priests are also sages and star watchers, and were associated in the Roman mind with astrology. The idea that pagan priests, led by a star, should have come from afar to worship the infant Jesus was irresistible , and the tale soon found its way into popular literature and iconography.

Although known to be an early work, this triptych is Memling's most monumental composition and one of his plastically most accomplished. A perfectly symmetrical, semi-circular line of bodies runs through the continuous space of all three panels, with the calm upward movement of the Reception of the Righteous into Heaven balanced by the turbulent Casting of the Damned into Hell on the opposite side. Although it was one of Memling's first creations in Bruges, it already displays impressive mastery. The work was commissioned by Angelo Tani (1415-1492), the Florentine manager of the Medici bank in Bruges, for the altar of his newly founded chapel in the church of the Badia Fiesolana in Florence.

But how many Magi were there? It is assumed there were three, though there have been odd representations in the Christian catacombs at Rome showing one with four and another with two. Its hard to precise who came up with their names, but the magical names of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego were soon adopted throughout Christendom; and these priests of Zoroaster, presumably baptised in their old age by Saint Thomas, were inexorably transformed into saints.

Much has been written, especially in France, about the possible influence of liturgical drama on medieval and early Renaissance art. The evidence is too meagre to argue about. Yet the use of our eyes, and the adding together of two and two, gives us some reason to believe that Memling has shown us a sight whose spendor we can scarcely imagine for ourselves: a “Jeu de Trois Roi” of late medieval Flanders.

But we may also admire the “Seven Joys” for its virtues as Christmas art and its simplicity of vision that underly its apparent complexities. For in the metaphysical sense, if not the technical, Memling was a primitive, whose work could possibly find its best audience among children: colors so clear that the painting sparkles; the well-observed horses; and since children are as bloodthirsty as anyone else, the massacre, but not so gory a massacre as to cause nightmares.

”During his career he and his workshop produced dozens of private devotional pictures and several large altarpieces — thanks to his exceptional productivity, there are more pictures by Memling than any other 15th-century Flemish painter. When I saw the giant Memling retrospective in Bruges in 1994, I realized that this was not without its consequences. Faced with so many blandly pretty Madonnas and stiffly drawn and rather empty altarpieces, one saw that here was a painter who, like his Italian contemporary Pietro Perugino, relied on a successful formula for most of his career. Although it’s heretical to think so, I found that only rarely did Memling create a vibrant, haunting work of art — among the exceptions were the Passion panel from Turin and The Seven Joys of Mary in Munich, the Crucifixion altarpiece from Lübeck, the Sacred Allegory from Strasbourg, the Shrine of St. Ursula, the overwhelming Last Judgment from Gdansk and the Lehman Annunciation — and nearly all of his portraits.” ( Paul Jeromack )

/a>

/a>

COMMENTS

COMMENTS