Some people call a lie told for a great and good purpose a “noble lie.” Our government engages in a noble lie, according to these people, when it lies to us for our own good. Let us suppose, for the sake of focusing on the issue of truth, that the lie really is for our own good. I believe we can confidently say that “noble lie” is an oxymoron that makes no sense…. but the nature of the big lie, because of its gargantuan proportions may be less easier to hunt and capture…

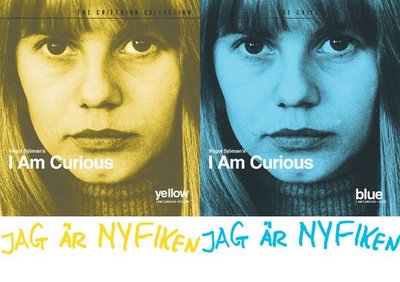

''Until that time comes it's safe to say that Criterion has been very good lately at cunningly selecting films that mirror the tensions in society right now, be it THE LOST HONOR OF KATHERINA BLUM, or this pair of radical movies made by Vilgot Sjöman in the late '60s and suffering from censorship problems both there and in the United States. Where do old groundbreaking sex films go when they have served their purpose? We watch them, use them, and discard them like spent tissues. YELLOW and BLUE have been a little hard to see, if not impossible. But re-seen today they seem fresh and still pertinent, as if the Disco years, the Reagan years, and the Clinton feel-good years never happened. We're right back to striving for sexual liberation and protesting wars.''

Herbert Marcuse felt that great art, the best art, is negative, destructive and irrational and therefore a valuable element in our society. Marcuse’s argument for the importance of the portrayal of negative powers in art is quite elaborate. In essence he combines Freudian psychology with a Marxian critique of the capitalist society. Freud’s psychology places a heavy emphasis on the role of (sexual) repression. The reality principle replaces the pleasure principle in young children. This is the basis of civilized society, and nothing can satisfy these unconscious desires of adults. The self which represses and is disgusted by what is repressed is the adult, social self while the self which delights in the repressed is the childish, anti-social self. This repression is exemplified by folk characters such as Peter Pan.

To Herbert Marcuse, Freud, in enunciating the doctrine of repression: a fundamental dicta that instinctual drives need to be repressed, to some degree in the interests of adjusting to a Reality Principle , that being the ability to recognize the claims of work, and to forego present pleasure for a future good; was not so much wrong as he was a prisoner of his time. Marcuse modifies Freud’s analysis by making a distinction between necessary and surplus repression. Necessary repression is necessary because it helps the individual to survive. However, surplus repression is not demanded by reality, but by other people ,such as rulers. Progress is an elimination of surplus and a lessening of necessary repression. However, Marcuse feels that surplus repression is being increased by the privileged sectors of society to ensure their dominance.

While the necessity to endure labor was still part of the human condition in Central Europe in Freud’s day, the radical transformation of technology in the twentieth-century changed this according to Marcuse. People today, argued Marcuse, suffer from surplus repression, not from an infantile inability to control libido. Work no longer rules. Marcuse, in a deliberate pun on Freud’s famous essay ”Beyond the Pleasure Principle” , argued that people are perfectly capable of living, if only they knew it, beyond the ”reality” principle.

Psychoanalysis, which in Freud’s day was a revolutionary doctrine, has in our day become a counterrevolutionary doctrine. It urges individuals to submit to an absurd society rather than attempt to transcend that society and break free not only of the sick or constricted society’s norms but of the very concept of what constitutes maturity and sanity in the modern world. Marcuse linked this idea with broader social and aesthetic contexts by asking why do the most powerful and outrageous claims get so quickly integrated into our society? Given surplus repression, and the theory of the unconscious we can divine Marcuse’s answer.

He thinks that the outrage people express at social transgression is overstated because it is a product of their inner conflict, between repression and our defenses against it. We recoil from it because we are drawn to the breach of the rules. Now, if it was necessary repression which was being challenged, we would have a duty (to preserve civilization) to constrain such outbursts. However, there is surplus repression. And, in order to conquer the surplus repression we must tap our infantile desire for release from all repression. Thus art serves a revolutionary role, it promises what can never be in order to obtain what should be. Again, quite Marxist. Is this a universal theory of art even if it’s correct? What happens to art if there is only necessary repression left?

Firstly, it is no good, perhaps invalid, to critique or assess Marcuse in terms of a nineteenth-century set of classic liberal values that he considered obsolete, and in light of today, probably are. It is the liberal creed , which is at the heart of the American understanding of history, that reason, reformism, and conciliation are central to the political process; even though Americans, by their actions, have from Shay’s Rebellion to the Civil War to the draft riots to the campus rebellions to the Iraq War, given the lie repeatedly to this saccharine notion of the American experience.

The reasonableness of a John Stuart Mill; the addiction to the notion of ideas as contending forces in a free market, has no place in Marcuse’s scheme. And if he was correct in his assessment of the contemporary reality, which he judges a hell, he was right to reject the piecemeal reforms that he saw as merely the patching together of a rotten structure that ought to be blown away by a typhoon. Accepting Marcuse on his own terms, the question is always how ”new” was his message and how true?

He stands in a long line of nineteenth-century utopian socialist and anarchist visionaries, men such as Proudhon, Kropotkin and Bakunin; men who inadvertently saw their thinking derailed and used to help prepare the way of Soviet style bureaucracy and terror. The critique against Marcuse is that the sense of surfeit and boredom, a result of affluence, results in the luxury of striking out at a world that engulfs and stifles them, while introducing toxic thoughts into the mainstream:

”Allan Bloom, for example, seeks to “rescue” university programs in the humanities from the perils of political protest and value relativism in The Closing of the American Mind. While higher education in the humanities is generally thought of as pursuing universally human aims and goals, Bloom is unwilling to admit that a cultural politics of class, a cultural politics of race, and a cultural politics of gender have historically set very definite constraints upon the actualization of the humane concerns of a liberal arts education. Bloom attributes a decline of the humanities and U.S. culture in general to the supposedly inane popularization of German philosophy in the United States today, especially the ideas of Nietzsche, Heidegger, and also Marcuse. These philosophers are regarded as nihilistic and demoralizing in part because they urge U.S. students to question nationalist commitments. Bloom asserts that we have imported “. . . a clothing of German fabrication for our souls, which . . . cast doubt upon the Americanization of the world on which we had embarked . . .” (p. 152). In a typically superficial remark he dismisses Marcuse saying he “began in Germany in the twenties by being something of a serious Hegel scholar. . . [who] . . . ended up here writing trashy culture criticism with a heavy sex interest . . .” (p. 226). Marcuse (in some ways very much like Bloom) valued high art and the humanities precisely because they teach the sublimation of the powerful urge for pleasure which in other contexts threatens destruction.’, ( Charles Reitz )

Thus Marcuse, is seen as a resurfacing of a nineteenth century German tradition; standing with the German idealist philosophers of catastrophism and violence, like the neo-Hegelians, Marx, Engels, and the violently anti-bourgeois Nietzsche. Marcuse conceptually would deny a kinship with Nietzsche, but the connection between Marcuse’s contempt for middle-class fraud, self-deception, and surfeit he sees about him, and that of the nineteenth-century visionary, can be fairly clear at times: ”What constitutes the chief characteristic of modern souls and modern books is not the lying, but the innocence which is part and parcel of their intellectual dishonesty. …Our cultured men of today, our ‘good’ men do not lie, that is true; but it does not rebound to their honor. The real lie… would prove too tough and strong an article for them in a long way; it would be asking them… to open their eyes… and learn to distinguish between ‘true’ and ‘false’ in their own selves.”

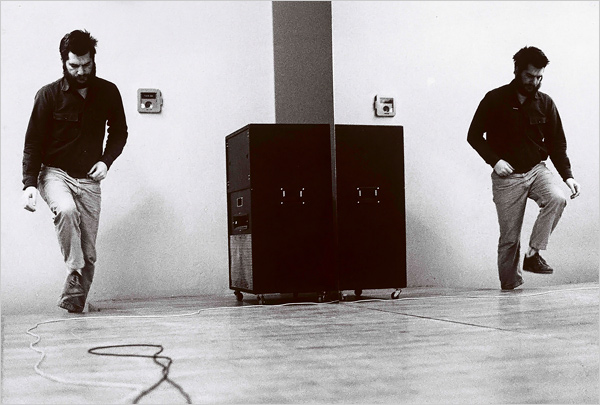

video still of Dan Graham performing “Performer/Audience/Mirror” in 1977. “Mr. Graham, 67, is someone whose work does not come easily to mind even for an informed artgoing public. In part this is because his restless intellect has never allowed him to settle into anything resembling a signature style or to be easily categorized.” Photo: Courtesy Dan Graham

”In The Objectivist of September 1970 Ayn Rand published the article “Herbert Marcuse, Philosopher of the New Left” by George Walsh. This article exposes Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979) as the fascist theoretician he was. Marcuse and Strauss were contemporaries, and their histories and outlook are similar. Marcuse too was born and raised in Germany, and as a Jew he fled to the U.S. in 1934. A bit more active than Strauss, in the early 1940s he worked for the OSS, the corrupt forerunner of the corrupt CIA. He too wrote many books, claiming to be fighting fascism, even as he was virulently anti-reason and anti-individual.

Ayn Rand had noted long ago the streak of fascism common to both liberals and conservatives, their protests to the contrary. Leo Strauss is the neoconservatives’ Herbert Marcuse. Were Ayn Rand alive today she might write an essay entitled: “Leo Strauss, Philosopher of the New Right.” Just as the New Left was the nakedly fascist strain of the Left, so the New Right – the Neocons – is the nakedly fascist strain of the Right. In some cases we even find the very same men in both groups! Many of the Neocons of today are the New Leftists of yesteryear. New Left versus New Right is a phony opposition, like a TV wrestling match. At base they are the same, and utterly opposed to Ayn Rand’s ideas.”

''This "ray gun," as Oldenburg calls it, hardly looks threatening. Its bloated shape, made out of flimsy papier–mâché, resembles a hairdryer as much as it does a weapon. It was made, however, in the spirit of assault, as a parody of artistic traditions and consumer culture. In the 1960s, this work was part of a cacophonous installation called The Street in the basement of Judson Memorial Church in lower Manhattan.''

In a sense, Marcuse is a type of Gnostic; one of those who reflect in religious vision or secular, humanity’s sense of exile from a state of bliss, a lost Eden, a lost communion with the world of light about whose psychological origins in the infant’s exile from the womb Marcuse’s own mentor, Freud, would have much to say. The underlying religious strain in Marcuse is, in any case, not difficult to detect. He who lays up worldly goods, he seems to say, lays up trash. There is a curious reversal of roles in Marcuse. His notion that the potential dissident in society, the now abject ”One-Dimensional Man” , has been bought off by spurious concessions seems to be a Leninist notion. Lenin warned the masses against the fraudulent concessions of the bourgeoisie; the reforms that accomplished nothing basic to change the ultimate character of society.

''“Am I a spaceman? Do I belong to a new race on earth, bred by men from outer space in embraces with earth women?,” Wilhelm Reich wondered in his book, Contact with Space, published in 1957 before his imprisonment by the federal government. Reich noted that this idea was first presented to the public in the 1951 film, The Day the Earth Stood Still. ''

Here Marcuse reveals the affinity with the Marxist-Leninists, whom he otherwise denounces. But in the classical Marxist conception it is ”religion” along with spurious material reforms , that is the opiate of the masses. Marcuse, on the other hand, seems to be saying that it is worldly goods; high minimum wages, television sets, BBQ’s , second hand luxury cars, that are the opiate of contemporary people which forever bar them from a quasi-religious state of consciousness that could be theirs. Quibbles with the semantics of the politics aside, there is a profound understanding by Marcuse of the aesthetics of art, and its role in a society, whether it is bourgeois or not; it expression as a reflection of ideology is inevitable, yet does not distract from potentially compelling critique, though he continues to be integral to an acrimonious and divisive debate.

”Marcuse understands alienation as anaesthetization— a deadening of the senses that makes repression and manipulation possible. He theorizes that art can act against alienationas a revitalizing, rehumanizing force. The educational goal Marcuse proposes is the restoration of the aesthetic dimensionas a source of cultural critique, political activism, and the guiding principles for the social organization of the future. In his estimation, our technological mindlessness and social fragmentation have to be educationally re-mediated through a broadened philosophy of the human condition — emphasizing particularly the aesthetic roots of reason — if ever we are to accomplish our own liberation. But Marcuse acknowledges that art can also contributeto an alienated existence. Alienation is understood in this second sense as a freely chosen act of withdrawal. It represents a self-conscious bracketing of certain of the practical and theoretical elements of everyday life for the sake of achieving a higher and more valuable philosophical distance and perspective. Marcuse contends that artists and intellectuals (especially) can utilize their own personal estrangement to serve a future emancipation. Art and philosophy (i.e., the humanities) can, by virtue of their admittedly elitist critical distance, oppose an oppressive status quo and furnish an intangible, yet concrete, telosby which to guide emancipatory social practice.” ( Charles Reitz )

COMMENTS

COMMENTS