”According to an apocryphal story, Henry Kissinger/André Malraux/an unidentified journalist once asked Chinese premier Zhou Enlai about the significance of the French Revolution. Zhou reportedly replied that it was still too early to tell. Taking this story in its intended spirit, one might reasonably ask the following question: If it is too early to determine the significance of a phenomenon that had occurred a century and a half earlier, is it at all reasonable to attempt to determine the significance of one that is a mere two and a half decades old? More specifically, is it possible for historians and other social scientists writing six years after the attacks of 9/11 (when most turned their attention to the problem) to typologize and historicize the phenomenon of jihadi movements such as al-Qaeda?” ( James L. Gelvin )

For many anarchists, to proclaim the aims of violence, and even the necessity and desirability of the act was one thing, but to breach that line and actually realize it, has been the great dividing point.Although most anarchists assumed the necessity of a violent revolution to overthrow the established order, pacifist anarchists such as William Godwin, Leo Tolstoy at the end of his life, and the Dutch anarchist, Domela Nieuwenhuis, fell short of condoning armed insurrection.

Few terms have been surrounded with as much myth and misunderstanding as “anarchism.” Part of the difficulty is that there are many kinds of anarchists. Though bound by the goal of social revolution the means could be sharply different. Contrary to the stereotype,many anarchists did not object to order itself but to the oppressive forms of order imposed by the capitalist state.In the late nineteenth century, anarchists like Albert and Lucy Parsons frankly acknowledged the belief shared by other anarchists in their circle that social transformation would only come through revolution, “through bloodshed and violence.”

”We are charged with being the enemies of “Law and order,” as breeders of strife and confusion. Every conceivable bad name and evil design was imputed to us by the lovers of power and haters of freedom and equality. Even the workingmen in some instances caught the infection, and many of them joined in the capitalistic hue and cry against the anarchists. Being satisfied of ourselves that our purpose was a just one, we worked on undismayed, willing to labor and to wait for time and events to justify our cause. We began to allude to ourselves as anarchists and that name, which was at first imputed to us as a dishonor, we came to cherish and defend with pride. What’s in a name? But names sometimes express ideas, and ideas are everything.

What, then, is our offense, being anarchists? The word anarchy is derived from the two Greek words an, signifying no, or without, and arche, government; hence anarchy means no government. Consequently anarchy means a condition of society which has no king, emperor, president or ruler of any kind. In other words, anarchy is the social administration of all affairs by the people themselves; that is to say, self-government, individual liberty. Such a condition of society denies the right of majorities to rule over or dictate to minorities. Though every person in the world agree upon a certain plan and only one objects thereto, the objector would, under anarchy, be respected in his natural right to go his own way. . . .” ( Albert Parsons )

'' I ended up taking a position on the property destruction issue which, like my gun-law stance, provoked a lot of eyebrow-arching among the old-line “Gandhi Groupie” contingents in The Movement™. Basically, I decided that if no humans were targeted or injured in a Black Bloc-style attack on corporate property, it was OK, and that it didn’t constitute “violence”. What the hell, I thought; when the windows on big banks and the fronts of Nike Town or Starbucks are smashed all to hell, do all the un-smashed globalized chain stores’ windows organize a solidarity commmittee? When the windows on all the Navigators and Explorers are smashed out within five blocks of the WTO meeting, do all the other SUVs organize a collection to cover the repair bills? Besides, what about all the destruction of human lives and communities being carried out by the corporations whose windows were smashed out during WTO Week? ''

In Europe, in the late nineteenth century, anarchist violence manifested itself in two forms: peasant insurrections and urban terrorism. The first flourished in the areas where anarchism has always found its main strength, in the industrially undeveloped parts of Europe, especially Italy, and a little later Spain. Here there were traditions of brigandage and savage peasant uprisings. Anarchism appealed because anarchist doctrines were in part a protest not only against the state but against modern capitalism and the necessary disciplines which the Marxists, for example, accepted as inevitable, of industrial society.

''I also suggested the reactionary Old New Left types consider the acts of the Berrigan Brothers who, by dragging cabinets full of draft records into a parking lot and setting them afire, helped impede business as usual for the Vietnam War, not to mention proabably saved a lot of young guys from dying in Vietnam. I also reminded the Gandhi Groupies to take a look outside the coddled world of US activists, and consider how demonstrations and direct action are done in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and pretty much the entire planet outside of the USA — the French students in 1968 flipping cars to use as barricades, striking Bolivian miners bringing dynamite sticks to protests because they know the police and soldiers aren’t there to protect them.''

Peasants bewildered and enraged by legal and financial regulations that seemed to rob them of their produce and that they could not understand, and small independent handcraftsmen threatened by the competition of mass production, were fertile soil for anarchist propaganda. They, rather than the industrial workers on whom the Marxists relied, formed the rank and file of the anarchist movement. One of the first acts of the various Italian and Spanish peasant insurrectionists, apart from church burning, was to burn local government

hives, the paper chains in which the peasant was enmeshed and his indebtedness recorded.Essentially, however, anarchism only provided a superstructure of theory for the deep seated, habitual violence of an oppressed rural population; the latter was just as evident in Ireland, where there was no anarchist propaganda at all. In such communities the bandit was often a folk hero; Bakunin adopted him as an honorary anarchist. ”Brigandage,” he wrote, ” is one of the most honored aspects of the people’s life in Russia… The brigand in Russia is the true and only revolutionary… the irreconcilable , unwearying, untameable revolutionary in deed. ”. He also spoke hopefully of what he called the childish and demonic delight of the Russian peasant in fire.

''The first recorded use of the A in a circle by anarchists was by the Federal Council of Spain of the International Workers Association. This was set up by Giuseppe Fanelli in 1868. It predates its adoption by anarchists as it was used as a symbol by amongst others. According to George Woodcock, this symbol was not used by classical anarchists. In a series of photos of the Spanish Civil War taken by Gerda Taro a small A in a circle is visible chalked on the helmet of a militiaman. There is no notation of the affiliation of the militiaman, but one can presume he is an Anarchist. The first documented use was by a small French group, Jeunesse Libertaire ("Libertarian Youth") in 1964. Circolo Sacco e Vanzetti, youth group from Milan, adopted it in and in 1968 it became popular through out Italy. From there it spread rapidly around the world.''

Rural anarchism, for all its atrocities, often had a certain naive innocence. Observers in Spain during the civil war in the 1930’s were touched by the simplicity, the complete faith and literalness, with which the peasants took their anarchist slogans and ran their anarchist communes.

The darkest side of anarchist violence was the urban terrorism that, while it was centered in France, swept across Europe between 1880 and the First World War and spread to the United States in the wake of European immigration. One inspiration for it was the assassination in 1881 of Czar Alexander II. Assassination became one of the facts of Russian public life. Between 1881 and 1911 the terrorists’ trophy bag included a minister of education, two ministers of the interior, a brace of generals, a prime minister, a grand duke, and, of course, a czar. Most of the Russian terrorists were not strictly anarchists but revolutionary democrats driven to isolated acts of violence by their sense of impotence in the face of czarist despotism and the inertia of the masses. Yet psychologically, they had much in common with the anarchist terrorists of Western Europe, who eagerly celebrated their successes as victory in a common cause. The latter were made desperate, paradoxically, not by the harshness of European political conditions but by their relative mildness. The coming of universal suffrage in the last quarter of the century, the growth of trade unions and parliamentary socialist parties, threatened to deprive the intransigent revolutionaries of all hope of mass support.

Most of the Russian terrorists were not strictly anarchists but revolutionary democrats driven to isolated acts of violence by their sense of impotence in the face of czarist despotism and the inertia of the masses. Yet psychologically, they had much in common with the anarchist terrorists of Western Europe, who eagerly celebrated their successes as victory in a common cause. The latter were made desperate, paradoxically, not by the harshness of European political conditions but by their relative mildness. The coming of universal suffrage in the last quarter of the century, the growth of trade unions and parliamentary socialist parties, threatened to deprive the intransigent revolutionaries of all hope of mass support.

'''Whose streets?' a threatening character in a face mask shouted inches from my ear. 'Our streets,' the mob replied. As I struggled to maintain the pretence that I was one of these hate-filled anarchists, I found myself plunged deeper into an alien, volatile world, where protesters either side of us were falling with nasty head wounds. Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/

Even Marxists, though they continued to mutter about the coming doom of capitalism, seemed to have abandoned revolution for the ways of constitutional legality. Only the anarchists remained obdurate, and it seemed all the more vital to them to demonstrate in some dramatic fashion that the class war was not dead. It was the Anarchist International Congress of 1881 that approved the ”Propaganda of the Deed”.

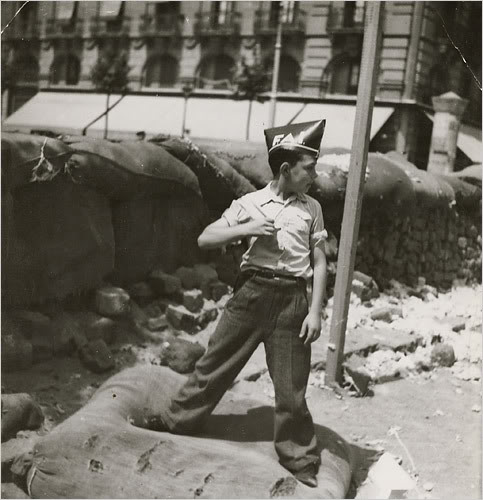

Boy wearing cap of FAI (Iberian Anarchist Federation), Barcelona, August 1936. Photo: Gerda Taro Taro died on July 27, 1937 while attempting to jump onto the running board of a car when it was struck by a tank. Pablo Neruda attended her funeral in Paris (held on her 27th birthday), as did the French writer Louis Aragon. She was viewed by the French and Spanish left wing as a martyr to the war and, indeed, Gerda Taro is the first woman photographer ever to have died while covering a war.

” There has been an emerging theory in which the phenomenon of nineteenth century anarchist terrorism is seen to prefigure the phenomenon of contemporary terrorism; whether this is developed as a defense mechanism for the existing Liberal-Democratic model as a rectionary device, or part of a more profound anaylsis in understanding the ”pathologies” of the ”diversity” that has been imposed on society, it is clear these are threats to the existing norms of what we presently have as ”freedom” ; Islamic activists in the West demanding segreated facilties which mirrors the demands of Orthodox Jews in Israel , which demand a peeling back of the assumption of ”integration”, which may open the door to even more fragmentation.

”In a speech given last November and in an article, Professor James L. Gelvin argues most forcefully for the existence of close similarities between nineteenth century anarchist terrorism and contemporary terrorism.1 In his talk Gelvin specifies six main areas of resemblance. These include the fact that both anarchists and al-Qaeda: number one, prefer action over ideology, number two, focus single-mindedly on resistance to an intrusive alien order, three: lack programmatic goals, four: pursue violence for its own sake, five: attack the state and the entire world system of nation states and, finally, operate through decentralized, semi-autonomous cells. Gelvin goes further than noting similarities, since he actually contends that al-Qaeda–style jihadism is a kind of anarchism, an Islamic anarchism, and indicative of the reemergence of anarchism as a force in world history after an approximately sixty year absence. Understandably, Gelvin concentrates on al-Qaeda, a subject that forms part of his general area of expertise, and spends little time explaining how the anarchist terrorists fit into his paradigm.”

''Also protesting against the G8 summit, if from much farther away, was a group called Anarchist Action. San Francisco police officer Peter Shields has been forced to take this group of clowns quite seriously. He has just been released from the hospital after being treated for brain swelling and a blood clot inflicted by protestors at a demonstration they organized. The anarchists drew Shields out of his car by throwing a mattress in front of it, then assaulted him as he emerged, gashing open his head with an unknown object. He is expected to recover and rejoin the force, but according to police spokeswoman Maria Oropeza, it is not known how long that will take. Although the justification for the San Francisco protest was the G8 summit in Scotland, the actual objective was the same as that of pretty much all left-wing protests and moonbattery in general: to spit at civilization, and if possible, to poke it in the eye. If Satan appears on earth, he may well come dressed as a clown. His army is ready and waiting for him.''

Whaen Gelvin refers to Islamic anarchism, he really means Islamic anarchist terrorism:

What about Gelvin’s fourth point, that Jihadists and anarchists, or better, anarchist terrorists, pursue violence for its own sake? One thinks immediately of the anarchist leader Mikhail Bakunin’s infamous statement (made even before he became an anarchist) that the ‘‘urge to destroy is also a creative urge.’’ One also thinks of al-Qaeda’s attack on the twin towers, which had only a roundabout connection with Bin Laden’s stated goal of getting the Zionists and Crusaders out of Islamic lands. 9=11 seemed to be more a piece of violent, symbolic theater, than concrete policy.

''The Unrestricted Dumping Ground A Judge cartoon from 1903, playing to fears of socialism, anarchism and the Mafia, imported “direct from the slums of Europe daily.” The background figure is that of the late President William McKinley, who was assassinated by the son of an immigrant two years earlier. Judge was a leading Republican magazine of the time, and was forever fretting about the effects of polluting the native racial strain---especially since most of the immigrants, once they won the vote, tended to vote for Democrats. ''

Nonetheless, similarities exist in terms of the worldwide scope and the styles of violence employed by al-Qaeda and the anarchists. In the early twentieth century, anarchist terrorism appeared to be a universal threat, like al-Qaeda today. Stunning assassinations and bombings took place in previously untouched or recently untouched areas, such as North and South America, and groups unaffiliated to anarchism, such as the terrorists of India, were co-opted into the Black International by the reports of alarmed and sensation-seeking journalists.

The only continent that avoided some act of real or alleged anarchist ‘‘propaganda by the deed’’ was Antarctica. Both al-Qaeda and the anarchists have been prone to select highly symbolic targets, be they the center of America’s war making power, the Pentagon, or, in 1893, that great den of the bourgeoisie, the Barcelona opera house. The symbolism of bombing the latter was enhanced by the fact that at the time it was performing ‘‘William Tell,’’ an opera about assassination in the name of achieving liberty….Another point of possible similarity regards acts of suicidal terrorism. Although they did not push it to the extremes of al-Qaeda, the anarchists carried out a number of suicide bombings and were often fatalistically resigned to dying after committing their violent deeds. This may be significant because suicide bombing only occurred or occurs in the anarchist and the most recent waves of terrorism. Probably the first suicide bombing of the modern era was carried out in March of 1881 by a Russian nihilist (although the nihilists were not anarchists) when he consciously gave up his life in order to ensure that his bomb got close enough to assassinate the Russian Tsar. The assassin stood one meter from his target and the ensuing explosion killed both assassin and victim. Emile Florion, the first French propagandist by the deed, tried to commit suicide after he had fired at a random bourgeoisie (but perhaps Florion is not such a good example since he was mentally unstable). Alexander Berkman, a Russian-Jewish immigrant to America, was planning to die by his own hand after he killed the ruthless, strike-breaking manager of the Carnegie steel works.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS