Yet who reads to bring about an end however desirable? Are there not some pursuits that we practice because they are good in themselves, and some pleasures that are final? And is not this among them? I have sometimes dreamt, at least, that when the Day of Judgment dawns and the great conquerors and lawyers and statesmen come to receive their rewards–their crowns, their laurels, their names carved indelibly upon imperishable marble–the Almighty will turn to Peter and will say, not without a certain envy when He sees us coming with our books under our arms, “Look, these need no reward. We have nothing to give them here. They have loved reading.”

– Virginia Woolf, from The Second Common Reader (quoted by Bloom in The Western Canon)

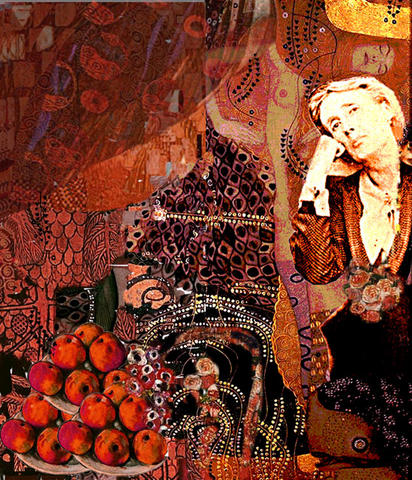

In the early years of the twentieth century Bloomsbury was bright promise and gaiety and wit. But all the while its most celebrated novelist was battling private demons that would one day overwhelm her….

Virginia Woolf’s genius was shaped by the special qualities of her parents: her mother’s delicate sensitivity and taste, her father’s intellectual power and neurotic inconsistencies. But her affections lay on the maternal side. As a militant feminist she came to disapprove of the patriarchal society in which she had been brought up , where women were worshipped as ministering angels and treated as household servants. Although her father, Sir Leslie Stephen, believed in the worth of human relationships, he insisted upon a suffocating ceremony that prevented his children from getting to know him.

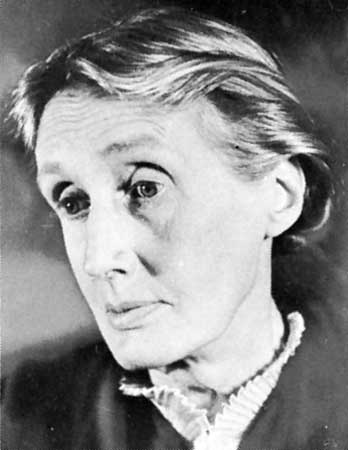

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) was a novelist, essayist, and short-story writer. Her modernist novels include Mrs. Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927), Orlando (1928), and The Waves (1931), and her nonfiction includes the feminist essayistic book A Room of One's Own (1929). She was a member of the London literary society, the Bloomsbury Group.

In her obituary notice for her father in “The Times” Virginia paid tribute to his vigor of mind, his honesty, and his endearing peculiarities, but as Mr. Ramsay in her novel “To the Lighthouse” , he is unimaginative, joyless, and tyrannical. He seemed full of contradictions; lovable to his friends, ruthless to his family; rich yet perpetually fearful of bankruptcy; intellectually enlightened but sexually repressed. A believer in freedom, he allowed his sons to go to Cambridge and choose their own careers; Vanessa was allowed to paint, Virginia to write. Yet he inflicted upon them all, and most especially his daughters, what Quentin Bell has called a “savage, self-pitying emotional blackmail.”

By the age of sixteen Vanessa had taken over the running of the house, with the help of Virginia, who was some three years younger. The atmosphere during the nine years between their mother’s death and their father’s was petrified with boredom and horror. In his last two years, Leslie Stephen suffered grievously from the cancer that was eventually to kill him, but even in this terrible illness his presence was suffocating.

"Why? The way you can look at a writer’s writing under the microscope. The rich comparative analysis it offers. The tiny pieces that are there for you to sift through – to linger on some pieces, to move more quickly through others. To get a quick character sketch, decide you like the way she pours her tea with her hand hovering over the other’s cup so as not to splash the other’s napkin, or how you don’t like the way he called his wife “Lapinova” – a rabbit is, after all, a hare, for Pete’s sake. What did The Complete Shorter Fiction of Virginia Woolf teach me about her writing? That to Ms. Woolf, the first line is essential. “People should not leave looking-glasses hanging in their rooms any more than they should leave open cheque books or letters confessing some hideous crime.” (You can only imagine what comes next.) “Since it had grown hot and crowded indoors, since there could be no danger on a night like this of damp… Mr. Bertram Pritchard led Mrs. Latham into the garden.” (Cha-ching! Makin’ the move.)"

While Leslie Stephen lay dying three or four floors below, Virginia’s half brother George Duckworth would fling himself upon her bed, kissing and embracing her in order, so he later explained to her doctor, to administer comfort. The result, Quentin Bell has written, was that “in sexual matters

e was from this time terrified back into a posture of frozen and sensitive panic.”As she helped to nurse her father, she must already have known that her release lay in her father’s death. Any consciousness of this would have filled her with guilt, and in fact, in 1904, a few months after her father’s death, she suffered another mental breakdown. She recovered, but her continuing obsession with death suggests an awareness that a part of her father lived on in her.

At the turn of the century Virginia’s elder brother Thoby, entered Trinity College, Cambridge. A handsome, charming young man, equally popular with artists and intellectuals, Thoby made friends who were to form the nucleus of the Bloomsbury group. When he introduced his university friends to his sisters, dressed in their long white Victorian dresses with lace collars and cuffs, shyly balancing parasols and looking as if they had stepped out of a romantic painting by Watts or Burne-Jones- the double apparition was breathtaking.

Leonard Woolf recalled that “it was almost impossible for a man not to fall in love with them, and I think that I did at once. It must, however, be admitted that at that time they seemed to be so formidably aloof and reserved that it was rather like falling in love with Rembrandt’s picture of his wife, Velasquez’ picture of an Infanta, or the lovely temple of Segesta.”

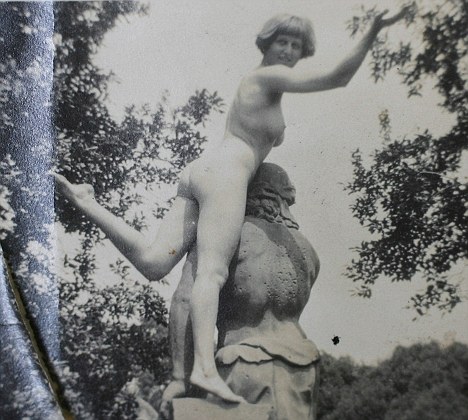

"Their vie bohème, as it so often is, was made possibly by the financial independence of the people fortunate enough to live it. You can see what a privileged life they really lived in these letters and pictures. Nannies and country homes are involved. Also nudity. Dora Carrington posed nekkid like a statue, and Frances Partridge is topless kind of a lot, actually. Only Virginia made a point of staying clothed in pictures."

Most people found Vanessa the more beautiful of the two. He figure was tall and imposing, her face perfectly oval with gray-blue eyes, hooded lids, and a full, sensitive mouth. She radiated a sense of mature physical splendor and moved with an undulating walk that earned for her the nickname ” Dolphin”. There was something magisterial about her presence that befitted a child of Leslie Stephenson. Yet part of this remote quality came from extreme vagueness. Her dreamy attitudes and wild inconsequences charmed some and exasperated others.

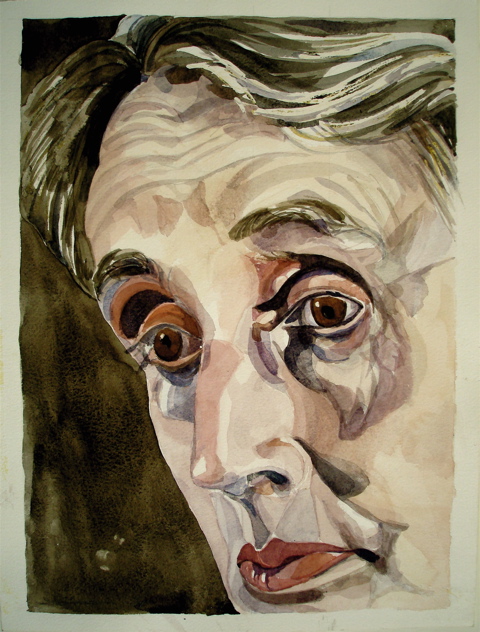

Virginia was a less comely figure. From out of an anxious , ethereal face her enormous green eyes gazed fearfully at the cold slow terrors of the world. She appeared to glide through life as through a dream that might suddenly turn, without warning, into a nightmare. Tall and slender, with a noble forehead and narrow, aquiline features, she had an ascetic, sexless charm that contrasted strangely with her vivid, cerebral enthusiasms. Leaning forward in her chair , a cigarette held limply in her long fingers, her head cocked to one side, she would talk in a throaty voice with a keen sensibility, wit, and an inquiring passion that was altogether different from Vanessa’s judicial tone. Her mental animation mounted rapidly as she spoke, and if someone stupidly dared to interrupt her in full flight, she would grow fierce, fling back some scathing remark, and revert to sullen, unapproachable aloofness.

"Standing on top of a statue with an arm and a leg held aloft a naked young woman strikes a pose. The rather provocative young woman in question is artist Dora Carrington, who in the early part of the 20th century was linked with the Bloomsbury Group. Such was their impact on history that one small corner of central London - Bloomsbury - is now indelibly linked with the Bohemian circle of friends, which included Virginia Woolf, EM Forster and critic Lytton Strachey. Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/

Their father’s death had given his children freedom. They moved from their depressing Victorian home to 46 Gordon Square in Bloomsbury. It was not then a fashionable area, and the move was considered by some to be deeply eccentric. It was here that Thoby began to invite his Cambridge friends, most of whom had by now left the university; and it was here that, as an alternative to Victorianism, the Bloomsbury group first came into existence.

They discussed questions of every sort, social, moral and aesthetic; and they spoke with a freedom that was highly unusual, employing four letter words in mixed company when the subject seemed to require them. The deed was very much the word. “Talking, talking, talking,” sighed Virginia in recollection of those days, “as if everything could be talked- the soul itself slipped through the lips in thin silver discs which dissolve in young men’s minds like silver, like moonlight.”

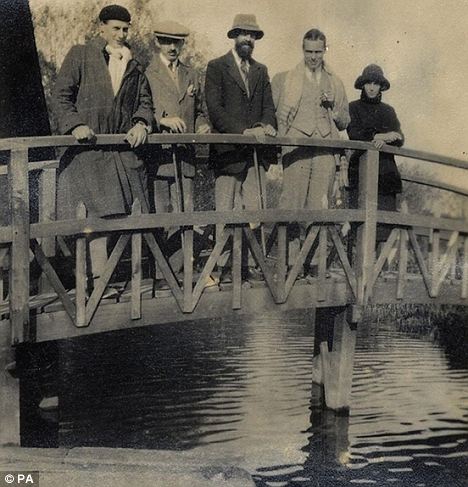

Bloomsbury set members Ralph Partridge, Noel Carrington, Catherine Carrington and Frances Partridge. Enlarge Frances Partridge, in a picture from the rare archive Today the Bohemian group of writers, artists and intellectuals are remembered as much for the complicated romantic entanglements that led to them being described as 'artistic lions' who 'lived in squares and loved in triangles' Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

The Bloomsbury Group was London’s little pocket of Bohemia; A high society group of artists, writers and intellectuals, who were as notorious for their liberal attitudes and tangled love lives as they were for their work. They founded an aesthetic which will forever be synonymous with eccentric British style. Most of this influence can be traced back to Walter Pater. The influence of Pater’s aesthetic on modernism has been substantial with particular regards to his conception of the novel as a work of art. Virginia Woolf, who was taught Classics by Pater’s sister Clara, provides the most pertinent examples of Pater’s work on aesthetics that was concerned with defining the dynamic between art and its subject.

Pater”s interest in classical mythology was transformed into literary applications that he made of myth in order to highlight Victorian social anxieties: In this context, particularly his treatment of the Dionysian-Apollonian antithesis. Pater had a genuine capacity for creating myths which reflect the consciousness of his own time.Although literary art never fulfilled Pater’s vision of it, he occupied a key and vital role in its evolution into modernism. A libertine, and homosexual, he had enormous influence on Arthur Symons and Oscar Wilde in particular:

"Mona Lisa was not well known until the mid-19th century when artists of the emerging Symbolist movement began to appreciate it, and associated it with their ideas about feminine mystique. Critic Walter Pater, in his 1867 essay on Leonardo, expressed this view by describing the figure in the painting as a kind of mythic embodiment of eternal femininity, who is “older than the rocks among which she sits” and who “has been dead many times and learned the secrets of the grave.”

“Regardless, there is no denying the influence that Pater had on Wilde’s aesthetics: it is palpable on every page Wilde wrote. In Wilde’s hands, Pater’s meditations on aesthetics are transposed into witticisms and aphorisms: “It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.” Wilde’s typically blasé attitude to imitation is illustrated spectacularly here in this aphorism that encapsulates Pater’s view on the relationship between art and its subject. His gift for communication and his wit meant that he was able to express Pater’s dense prose into a more palatable idiom. At the same time, as Wilde recognizes, the essential difference between them is that Pater was simply too “frightened “of asserting his views on art. In contrast, he revelled in the media circus of his own creation; he became the parody of the media’s parody of Walter Pater.As Wilde plundered Pater’s aesthetic in his own work in the late-1880s the dynamic of their relationship began to change… There is another facet, I believe, that being that Pater disliked how Symons and Wilde were reflecting on his aesthetic. Their outlandish exaltations of style as the supreme value reinforced the media criticisms of Pater’s Renaissance even though Wilde revises this idea in Intentions (1891).”

All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music. — Walter Pater In 1863 Édouard Manet scandalized the art world by painting a picture of a picnic.

Virginia Woolf on Walter Pater: There is no room for the impurities of literature in an essay. Somehow or other, by dint of labour or bounty of nature, or both combined, the essay must be pure — pure like water or pure like wine, but pure from dullness, deadness, and deposits of extraneous matter. Of all writers in the first volume, Walter Pater best achieves this arduous task, because before setting out to write his essay (“Notes on Leonardo da Vinci”) he has somehow contrived to get his material fused. He is a learned man, but it is not knowledge of Leonardo that remains with us, but a vision, such as we get in a good novel where everything contributes to bring the writer’s conception as a whole before us. Only here, in the essay, where the bounds are so strict and facts have to be used in their nakedness, the true writer like Walter Pater makes these limitations yield their own quality. Truth will give it authority; from its narrow limits he will get shape and intensity; and then there is no more fitting place for some of those ornaments which the old writers loved and we, by calling them ornaments, presumably despise. Nowadays nobody would have the courage to embark on the once famous description of Leonardo’s lady who has learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants; and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy, and, as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary . . .

Miriam Roth "In his conclusion to The Renaissance, nineteenth-century critic Walter Pater presents two ways to interpret art and, more broadly, sensory experience. First, Pater offers an objective lens: a kind of suspension of the self that awakens the viewer to the immediate, natural world and its intricate patterns. Beginning from “without” takes us outside “those thick walls of personality” that can blur perception, enabling us to map a “clear, perpetual outline of reality.” Pater then introduces an exciting but problematic second option: to “begin with the inward world of thought and feeling.” In succumbing to the free-flowing moods and associations of the individual psyche, Pater warns, the interpreter risks isolation, confusion and outright error. This “whirpool” of a landscape leaves the voyager no footing but the “tremulous wisp” of his own shifting impressions. Neither of Pater’s poles, of course, can sustain permanent life. By necessity, we hop between these territories on a daily basis. We identify spaces for scientific observation and those for open-ended musing, adjusting our responses accordingly. But Pater encourages us to aim for a balance between fact and feeling."

One of the most beautifully-written books in the English language, The Renaissance has an undeserved reputation for purple prose and an all-too-deserved one as the holy book of decadent aestheticism. “I wish they would not call me a hedonist,” Pater once complained, “it gives such a wrong impression to those who do not know Greek.” As we all know, however, the real reason we are discomforted by any description of ourselves is the possibility that it might give people the right idea. Pater was an aesthete, and his book is the first and best English-language manifesto of aesthetic life. Here’s a taste (and just a taste) of what Pater is capable of:

On Pico Della Mirandola: “And yet to read a page of one of Pico’s forgotten books is like a glance into one of those ancient sepulchres, upon which the wanderer in classical lands has sometimes stumbled, with the old disused ornaments and furniture of a world wholly unlike ours still fresh in them.”

On Michelangelo: “A certain strangeness, something of the blossoming of the aloe, is indeed an element in all true works of art: that they shall excite or surprise us is indispensable. But that they shall give pleasure and exert a charm over us is indispensable too; and this strangeness must be sweet also–a lovely strangeness.”

On Michelangelo’s pietas: “He has left it in many forms, sketches, half-finished designs, finished and unfinished groups of sculpture; but always as a hopeless, rayless, almost heathen sorrow–no divine sorrow, but mere pity and awe at the stiff limbs and colourless lips.”

On the Uffizi Medusa (also the subject of a poem by Shelley): “What may be called the fascination of corruption penetrates in every touch its exquisitely finished beauty.”

On the proper use of philosophy: “Philosophy serves culture, not by the fancied gift of absolute or transcendental knowledge, but by suggesting questions which help one to detect the passion, and strangeness, and dramatic contrasts of life.”

On aesthetic experience: “Not to discriminate every moment some passionate attitude in those about us, and in the very brilliancy of their gifts some tragic dividing of forces on their ways, is, on this short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening. With this sense of the splendour of our experience and of its awful brevity, gathering all we are into one desperate effort to see and touch, we shall hardly have time to make theories about the things we see and touch.” ( Brian A. Oard )

COMMENTS

COMMENTS