Banning the corset and into the harem. Read my Body. “From the idea that the self is not given to us, I think that there is only practical consequence, we have to create ourselves as a work of art.” ( Michel Foucault ) A decree from fashion’s dictator Paul Poiret delivered women from one snare, but he would set new ones: the hobble skirt and the calorie count. It was the war of petticoat junction. Willy nilly chilling on the frillie….

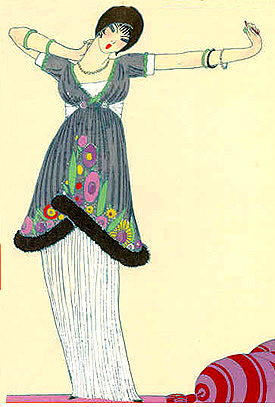

"With spendid eyes... and a cruel mouth like a carp's," this "glittering, slouching" young thing epitomizes the new ideal created and vigorously marketed by Paul Poiret. Her high waisted dress, a 1912 sensation, includes a Poiret trademark: the lampshade tunic. Drawn by Georges Lappe.

“In the annals of fashion history, Paul Poiret (1879–1944), who called himself the “King of Fashion,” is best remembered for freeing women from corsets and further liberating them through pantaloons. However, it was Poiret’s remarkable innovations in the cut and construction of clothing, made all the more remarkable by the fact that he could not sew, that secured his legacy. Working the fabric directly onto the body, Poiret helped to pioneer a radical approach to dressmaking that relied more on the skills of drapery than on those of tailoring.”

Surely as much as any man does, Paul Poiret, couturier, merits a niche in the women’s liberation hall of fame. For he was the fashion revolutionary who, at the beginning of this century, freed women from the corset. “I declared war on the corset,” Poiret said, “Like all great revolutions, mine was carried out in the name of Liberty, to give free play to the stomach, which could dilate without restriction.”

Others had been trying to achieve this since the 1850’s, but with little success.There had been, for instance, the dress-reform ladies, with Amelia Jenks Bloomer in the forefront, and the British Aesthetes, with their anti-whalebone doctrine and unfettered Grecian draperies. But Poiret had an advantage over his predecessors. In addition to the usual attributes of the dedicated revolutionary; a sense of mission and a full measure of ego; he possessed a remarkable aptitude for drawing attention to himself.

"Paul Poiret's 1909 collection introduced his "Hellenic" gowns, that draped the body like tunics. The following year, he offered his own take on the Directory look with high waists and straight skirts, though in a bow to early 20th century modernism, he incorporated veiled bodices, with heavier transparent materials. The Bourgeoisie were at this point, unstoppable as a moralizing force, and the Victorian ethics prevented the Bacchanalia/nudity aspect of the original clothing. Quelle Domage."

This instinct for showmanship carried him to power in 1907, to reign as king of fashion for nearly a quarter of a century. During this time he left his imprint on dress, art and decoration. Traces of his influence linger with relaxed , unconstructed clothing that reveals the figure, and in the enduring revival of the Art-Deco style that he to a large extent created.

“Imperious and Venetian” in his own eyes, and looking to Jean Cocteau like “some sort of huge chestnut,” Poiret presented an impressive appearance. Once he took over the world of fashion, he had no trouble in exerting a one-man rule, with a range of activities that extended from the designing of theatre costumes to the breaking down of social barriers. He expanded haute couture by branching out into related fields such as fabric design and interior decoration, and into the production of perfume and accessories, thus paving the way for wide-ranging enterprises of the mode like those of Dior, Cardin and Chanel.

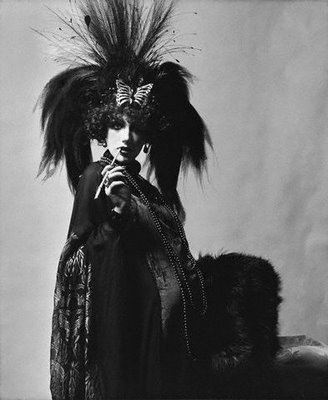

Poiret launched “the age of gold lamé. ” In his heyday, on the eve of World War I, he put women, uncorseted women, into pearl chin-straps and sent them off to the races wearing satin turbans spiked with tufts of aigrette feathers, trouser-skirts, and gold gold-embroidered Chinese cloaks. It was all part of a thrilling new vogue for Neo_Orientalism, a movement sparked by Poiret and Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe, a vogue that made the generous Edwardian S-shaped figur

ith its layers of lacy, complicated underclothes, seem hopelessly “demodé”.

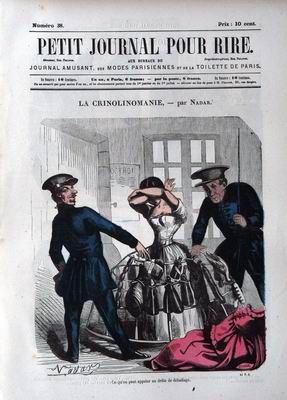

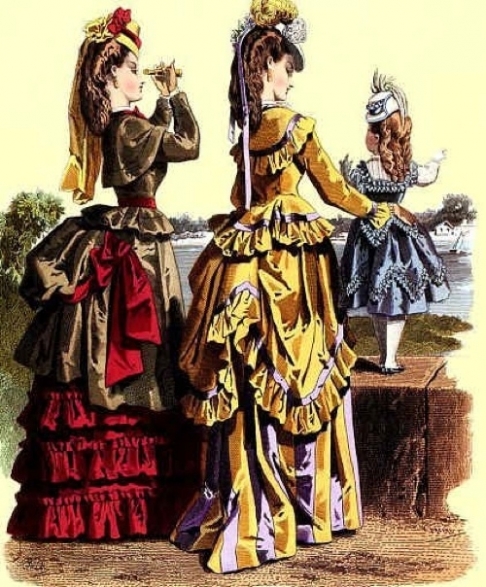

"Unlike Renaissance women, Victorian women were very body conscious. Sexy meant having the smallest waistline humanly possible-- in order to achieve this look, women wore corsets. Some corsets were wound so tight that women could hardly breathe, to the point where sitting down was completely out of the question. Many women would even break ribs trying to get their waistlines down to an inconceivable 12 inches. Layered petticoats, hoops, and bustles became very popular, all of which magnified the largest parts of the body-- can you say, “Baby got back?”

“Yes,” wrote Poiret, “I advocated the fall of the corset. I liberated the bust. When I declared war on the corset, women’s bodies were divided into two distinct masses and the upper lobe appeared to be pulling the whole derriere section behind it, like a trailer.”

The elegant corset, of heavy colored silk or satin trimmed with real lace and ribbon bows , consisted of ten to fifteen curved pieces, not counting the gussets, and was traversed from end to end by dozens of whalebones and steel stays. Under it, a lady wore a garment called a chemise, which looked like a long nightshirt; over it, she-more likely her maid-hoisted voluminous linen pantaloons. On top of all this went a corset cover, a decorous bodice that concealed her stays. Finally, before being button-hooked into her dress, she got into one, two, or even three elaborate petticoats coyly known as “frillies” . The deployment of frillies was a tactic every flirt had to master. “As I knew my frillies were all right,” said Elinor Glyn’s Elizabeth in “The Visits of Elizabeth”,” I hammocked- and it was lovely”.

The height of the corset and frillies era was “la belle époque”, when “Frou-Frou” was having her moment at Maxim’s and when the real standard bearers of the mode were the flamboyant demimondaines. These imposing creatures held up their vast and snowy bosoms with stiff, boardlike constructions that ironed out their plump stomachs and pinched their waists in sharply at the back.

The overnight they disappeared. The images of their “grandes toilettes” and jewelled dog-collars vanished from the gilded frames of the theatre loges in what Cocteau had described as a sort of lap-dissolve: the hard lines of the great cocottes gave way to the flid ones of the new ideal- the glittering, slouching Poiret girl in her flowing, high-waisted dress, with splendid eyes, a headache band, curly hair dressed like a poodle’s, and a cruel mouth likea carp. Girl’s became conscious of their bodies and of calorie counting. Extra fat could be covered up by petticoats and leg-of-mutton sleeves, but not by the slinky Poiret line.

"The painting above depicts La Pâtisserie Gloppe on the Champs Élysées in 1889. Béraud evokes the magical use of mirrors in the shop's interior, the behavior of its patrons, the bourgeois ordinariness of the scene. It is rooted in the here and now, which has become the there and then, and so oddly poignant, in a way the Impressionists rarely are. Béraud recedes into his work, creating a space for us to enter this bygone moment of a bygone age. The image has something of the authority of a photograph and something of the intense subjectivity of the artist's desire to record just what he saw, just what he thought we might have seen if we had been with him that day in the shop, and no more. He has created a profoundly democratic work of art, radically out of step with the neo-Romantic egocentricity of the 20th-Century modernist."

Years ahead of Rudi Gernreich’s topless clothes and Saint Laurent’s see-throughs. Poiret shocked he conventionally-minded by recommending that his customers wear nothing at all under the transparent tops of his dresses, advice that was eagerly taken by a fearless but nt always shapely vanguard. The bra, as we know it, had yet to be invented. Breasts a la Poiret were breasts as nature made them, without benefit of modern sports and exercises,lifted only by grosgrain cummerbunds he sewed inside the rib cages of his Empire style dresses.

Pre-Poiret, overendowed ladies had worn “correctors” or “flatteners,” while the underendowed had filled themselves out with the contemporary version of falsies- flounced linen “amplifiers” . Such rectifiers were regarded as an improvement over both the cotton wadding that was stuffed into the tops of nineteenth-century corsets and then padded “bust-improvers” introduced in th 1880’s by Charles Frederick Worth, who foght a long, lonely battle against the cumbersome crinoline.

Maison Worth 2011."O legado da casa Worth, fundada por Charles Frederick Worth em 1858 começou a ser revivido nesta temporada outono/inverno de alta-costura. A pegada foi semelhante à de Givenchy no quesito exclusividade intimista, já que não rolou desfile, superprodução nem nada, mas a apresentação foi ovacionada no mundo da moda. Fato. E foi babado a complexidade da coleção assinada pelo designer Giovanni Bedin. "

At that time, a handful of Paris designers led by Worth , dictated the styles which were then worn by a few choice ladies. Sooner or later, the rest of the world soon followed their example. Their clients included almost every royal family in Europe. While Worth dressed the aristocracy, the rival house of Doucet produced flashier clothes for the noted actresses and demimondaines for notables such as rajane and Sarah Bernhardt. Poiret was hired as a sort of “pomme-frites” specialist but was appalled by the style ethic of the house. Charles Frederick”s tastes had run to dresses festooned with telegraph wires on which flocks of swallows perched , or to embroideries of large snails. Jean Gaston for his part, was upset by Poiret’s novel and liberal interpretations of elegance. “Yo call that a dress?” he would ask, looking at one of Poiret’s tailored models. “I call it a piece of trash.”

"The persistence of the haute couture is as roundly questioned and doubted and debated as the survival of painting or the supposed death of Broadway. Some may have doubted that the couture would survive its founder, the entrepreneurial Charles Frederick Worth. In the early years of the twentieth century, Paul Poiret took couture into an admittedly dangerous path of change, responding to Orientalist and social sirens, but even more to the beckoning of commerce and the use of the couture as a generating engine for fashion and fragrance broadly disseminated. "

On Charles Frederick Worth: “I always thought it was odd that an English man founded to what seems to be such a prestigious FRENCH instution. Although he is credited with founding Haute Couture I have reason to believe the system has it’s roots going all the way back to Louis XIV. As explained by my European history professor, it was then that many crafts held in esteem by the noble and wealthy were instituionalized as part of a sort of reclaiming of lucury objects by the nobility. While Worth may have been the one to create the modern system as we know it now, the roots of Haute Couture go back way before him.”

Poiret then started his own house, and began putting on his fashion “defilés” , the first shows of their kind. A talented young photographer named Edward Steichen took soft-focus pictures of them. Their stance developed into the round-shouldered, hipbones forward gait that lasted through the twenties and that Cocteau called ” the praying mantis walk”.

In addition, Poiret set the establishment back on their heels with his startling use of color: morbid mauves, neurasthenic pastels and wahat he called “rough wolves” that made his neutral colors “sing”. He chucked the corset, but he set a new snare. “I shackled the legs… women complained they could not walk anymore, they could not get into a carriage. And yet everyone wore the narrow skirt”. With the hobble skirt came other Poiret trademarks: the soft clinging bodice, the loose harem pants, Grecian draperiesand he lampshade tunic.

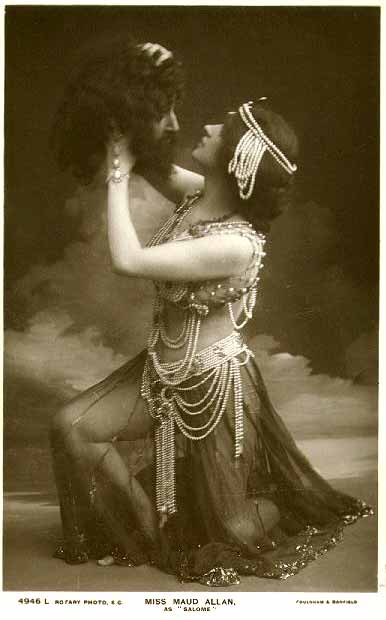

The draperies suited his friend Isadora Duncan, whom he introduced to paris at one of his lavish parties, and were also appropriated by England’s answer to Isadora, Maude Allen, who popularized he early see-through style sometimes referred to as “Le Nude”. The mysterious East had become all the rage; and Poiret who had near been anywhere near Asia was largely responsible for this uncertain mélange of Oriental motifs that characterized the fashions of the day. He shifted his inspirational sights from classical Greece to Persia to ancient Egypt to China and back again before the public could catch up with him. Poiret was clearly the vanguard of the bourgeoisie as a moralizing force behind the new values and the explosive potential of mass produced fashions that would work its way down the food chain and into derivative and complementary products.

"Fabulously influential designer Paul Poiret (1879 – 1944) discarded corsets and successfully disseminated an exotic Middle Eastern look including Turkish harem pants (that again, resembled the Bloomer costume silhouette) in 1911. This was purely an aesthetic choice and not a political statement on his part (he was also the inventor of the distinctly impractical hobble skirt), but it was threatening to social and religious conservatives nonetheless and that same year the Vatican campaigned against the “harem trousers” as morally objectionable, even while women’s legs were still completely obscured. While popular in wealthy fashionable society, Poiret’s exotic styles were not worn by lower or middle class women or dress reformers — but I believe the Parisian interpretation of oriental styles hastened the ultimate acceptance of trousers for women, since it removed the politically radical (and implied lesbian) stigma."

ADDENDUM. The Docile Versus the Active Self: ( Liz Eckermann )

“Foucault’s early works on the production of docile subjects and his later writing on the active self, as elaborated in volumes two and three of the History of Sexuality (The Use of Pleasure and The Care of the Self), prove singularly fertile in providing conceptual tools for understanding the body from a sociological perspective and specifically for gaining insights into the historical forces behind the modern ‘epidemic’ of self-starvation. His ideas have also formed the focus of new therapeutic techniques for dealing with such ‘disorders’, and these techniques specifically apply Foucault’s ‘general spectrum of power’ .

White and Epston note the use of analyses of power in therapy literature as traditionally representing power ‘in individual terms such as a biological phenomenon that affects the individual psyche’ or as ‘individual pathology that is the inevitable outcome of early traumatic experience’ (White and Epston 1989: 25). They identify attempts to apply Marxist class analysis in terms of power in the relations of production and ‘a number of feminist analyses of the operation of power.. . as a gender-specific repressive phenomenon’ which they see as having ‘sensitized many therapists to the gender-related experience of abuse, exploitation and oppression’. However they argue that ‘it is important to consider the more general spectrum of power as well, not just its repressive aspects, but also its constitutive aspects’; thus the work of Michel Foucault is important .

Foucault’s work on the disciplined society provides an analysis of the connectedness of the body, self and society, thus combining the macro and micro traditions of sociological analysis . Although his earlier work minimises the role of agency and the ‘self’, he refers to the politico-anatomy of the body and the bio-politics of the society as being inseparable parts of the general exercise of power. One of Turner’s unique contributions to a sociology of the body in extending Foucault’s analysis is to draw parallels between regimes of given societies and the regimes people apply to their own bodies. An administered society develops in response to the fact that all societies are confronted by four tasks, namely: the reproduction of population in time, the regulation of bodies in space, restraint of the interior body through disciplines and representation of the exterior body in social space (Turner 1984: 91). Self-starvation, and the ascetic practices that accompany it, reflect the overlap between these levels of administration. Self-starvation may represent a personal solution to a broader social problem of lack of order and control. This process is also normalised in the self-starvation that accompanies World Vision’s 40-Hour Famine, whereby ascetic practices of starvation at an individual level are used to appease social guilt about structural inequality globally.

…Foucault’s analysis of the extent to which bodies are ‘inscribed in discursive practice’ provides a framework to understand how the dogma of weight-reducing discourse (which is legitimated in public health campaigns) problematises the body, especially the female body, which is seen as in need of alteration both by the ‘owner’ of the body and by medical and public health institutions through the medical gaze. Spitzack’s analysis suggests that the use of Foucault’s framework of discursive power can turn a self-induced ‘disease’ category into a political issue. ‘Surveillance of the self plays a central role in domination strategies’ which constitute weight-reducing discourse. The individual views her body as ‘ultimately untrustworthy’ and its desires as ‘capable of taking her over’. As Foucault explains, the separation of mind and body:

permit[s] individuals to effect, by their own means, a certain number of operations on their bodies, their own souls, their own thoughts, their own conduct, and this in a manner so as to transform themselves, modify themselves, and to attain a certain state of perfection, happiness, purity, supernatural power. (1981: 367)

COMMENTS

COMMENTS