“The doppelgänger represents the side of our nature which must be suppressed in a civilised ordering of society.When the straitlaced Presbyterian physician of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde drinks his potion, he releases the more feral and lustful part of himself. Critics have argued that Stevenson was talking about the effect of narcotics – alcohol and drugs – on the Scottish psyche. He may also have been thinking in terms of the creative impulse: all writers, after all, are divided selves, populated by multifarious characters and voices.

In Hogg’s scheme of things, however, it is one particular tenet of Christianity that seems at fault.Antinomianism, according to Chambers Dictionary, is the belief that ‘Christians are emancipated by the gospel from the obligation to keep the moral law, faith alone being necessary’. In other words, if you are one of the ‘chosen’, one of God’s elect, then by implication you can do no wrong. Whatever you do must be right and must be good.You are forever justified in your actions.”…

"...19th century artwork by J.M Wright from an 1842 edition of the Complete Burns (engraved by S. Smith), depicting the witches’ dance in one of Burns’ most famous works, Tam O’Shanter, a grand example of the book illustrator – and the engraver’s - art (image borrowed from the Sexy Witch blog)

In the late eighteenth century, a Scottish town without wealth or size or power became pre-eminent among the great cities of Europe. Who turned Edinburgh into the “Athens of the North” ?

In 1766 Edinburgh most emphatically did not look or feel or smell like a center of enlightened thought and classical ideals. Until only a few years before , it had seethed with dark royal conspiracies and fierce theological disputes, centuries apart in spirit from the European Age of Reason. Physically, it was peculiarly grim and gothic. The chief amusements were the city’s uncomfortable, dimly lit taverns, and when an Edinburgh man went to a tavern he expected to return home drunk. Edinburgh in the Age of Reason was a city of sots.

For all its Calvinist upbringing, the city was a remarkably raucous place. An Englishman named Edward Topham, visting there in 1774-75 , was amazed to discover that the “shrine of festivities” for the “First People of Edingurgh” was none other than the oysterhouse where men and women gathered round a vast table, stuffed themselves with oysters, drank potsful of porter, and then crowned the evening dancing hectic reels. The music would commence, observed Topham, and up the ladies would “start, animated with new life, and you would have imagine they had received an electrical shock, or been hit by a tarantula.” The people of Edinburgh, he noted, “are exceedingly fond of jovial company.” Since aristocrats, lawyers and tailors still lived together in the same apartment houses, the affluent taking the middle floors, they were none too fussy about the mingling of classes. One of Edinburgh’s innumerable lawyers, James Boswell, once warned Rousseau, of all people, about the “shocking familiarity” of Scotsmen- that is, their woeful disrespect for the distinctions of rank.

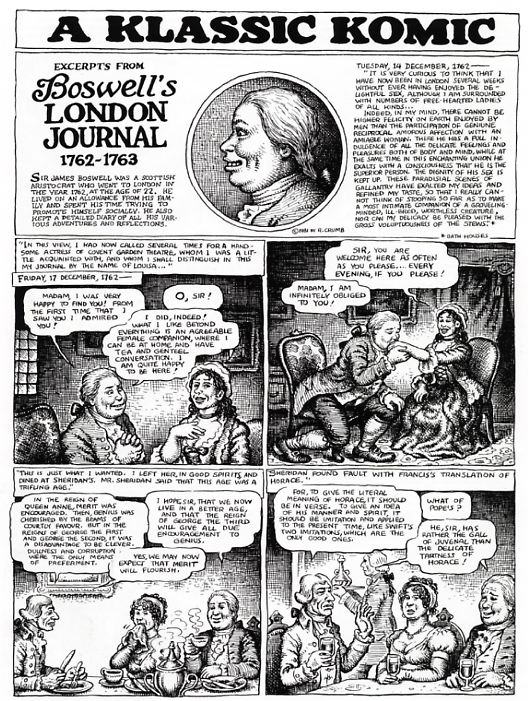

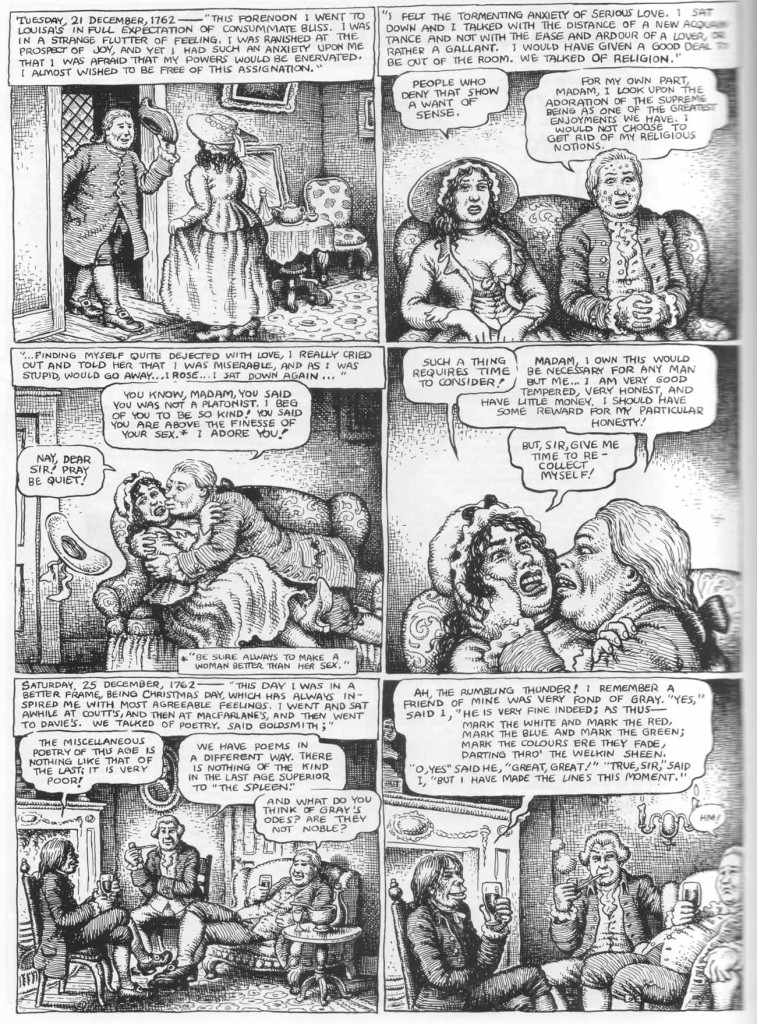

"Boswell's extensive and frank diaries were discovered in the '20s, and since the '50s have enjoyed slow publication through Yale University Press. Crumb's "Boswell" recreates 12 entries from James Boswell's licentious and literary diaries. The excerpts begin on Tuesday, December 14, 1762, and proceed through Thursday, July 28, 1763. In the first entry, Boswell laments that he has not partaken fully of London's sexual offerings. By the second excerpt, dated Friday, December 17, 1762, Boswell has attempted to seduce an actress whom he calls Louisa, after which he has dinner with a churlish Thomas Sheridan and his wife. On Tuesday, December 21, 1762, Boswell is found sitting next to Louisa on a couch, when he suddenly flings himself on her, only to be rebuffed. On Saturday, December 25, 1762, Boswell makes the rounds of various notables, including the actor and bookseller Thomas Davies and a simian-looking Oliver Goldsmith; Boswell beams as he listens to them debate the merits of the poet Thomas Gray. Finally, on Wednesday, January 12, 1763, Boswell conquers Louisa, having sex with her five times in one night, by his count (Boswell was 22 at the time). Skipping ahead, on Thursday, January 20, 1763, Boswell has a sleepless night, thanks to guilt feelings over Louisa and an eruption of gonorrhea. On Thursday, March 30, 1763, Boswell has sex with a whore in a park, and then on Tuesday, April 12, Boswell passes on a large-rumped whore who demands too much money. On Thursday, May 19, 1763, Boswell takes two whores to an inn, and then on Friday, May 20th, Boswell makes the rounds with some of his intellectual friends"...

Despite the general harshness in the mores and manners of the city, Edinburgh was already a major intellectual center when Topham was trying to convince his fellow Englishmen that the detested Scots were worth their “attention” . In the year of his visit, there sat at the pinnacle of Edinburgh society the most penetrating, the most celebrated, the most controverisal philosopher in Europe, none other than the great David Hume, who had returned from Paris to his native city in 1769 and found it so much to his liking he was resolved never to leave.

Soon to settle down in Edinburgh too, was Hume’s good friend Adam Smith, then completing “The Wealth of Nations” but already famous in Europe for demonstrating in his “Theory of Moral Sentiments” one of the fundamental tenets of Edinburgh thought, that men were born with an innate moral sense.

" Finally, on Thursday, July 28, Johnson and Boswell are shown walking down the street, when a hooker, whom the more puritanical Johnson shoos away, approaches them, after which Johnson philosophizes about her lot in life. In his text-heavy adaptation, Crumb easily contrasts the vast difference between Boswell's idealistic and even fanish adulation of various writing gods and the gross indecencies he pursued in private. One of Crumb's corollary tasks is to evoke 18th-century London and its various objects, such as canes, beer steins, pipes, draped beds, carriages, and cravats, as well as to render the likenesses of his subjects as accurately as possible while still having the Crumb "flavor." Yet it is also amusing to see how much this degraded and packed world resembles the modern one that Crumb usually draws. In the last panel, a broad-backed Johnson is helped down the narrow street on the arm of Boswell, the buildings crushing in on them as if in a badly drawn stage set. Crumb is in fact still in his element, pondering street life and the secret byways of lust. "There are a lot of things going on in Boswell's diaries but th

are a couple of contractions that I wanted to bring out," Crumb told Mercier. Despite its modesty and subservience to its subject matter, "Boswell" announces a major change in Crumb's work. It is also remarkably of a piece with Crumb's other work — showing a character in the throes alternately of self-doubt and lust. ".

It was a society that relished, to a remarkable degree, high-flown abstract discussions. As the Reverend Sydney Smith, a celebrated English wit, once said, he spent five years in Edinburgh “discussing metaphysics and medecine in that garret of the earth.” The people, he said, “are so imbued with metaphysics that they even make love metaphysically. I overhard a young lady of my acquaintance, at a dance in Edinburgh, exclaim, in a sudden pause of the music, ‘What you say, my Lord, is very true of love in the abstrait, but’ – here the fiddlers begin fiddling furiously, and the rest was lost.” Smith was not exaggerating. An amoruos Edinburgh lady once tried to ensnare Robert Burns by insisting that she and the young poet were kindred in their feelings, “tho’ the pen of Locke could not define them,” which is assuredly the metaphysics of temptation.

"This group portrait by Henry Singleton shows the author James Boswell with his wife and three of their children. Boswell is best known for his close friendship with Dr Samuel Johnson. His biography of the famous literary man, ‘Life of Johnson’, was published in 1791 and is widely regarded as one of the best biographies ever written. He also published a number of journals that document their travels together, including the celebrated tour to the Hebrides in 1773. Boswell’s personal diaries reveal another aspect of his character – that of an amorous adventurer. His wife, Margaret Montgomery, turned a blind eye to most of his drinking and womanising. "

“Every gentleman a drunkard and every drunkard a gentleman.” In eighteenth century Edinburgh, temperance was an unknown virtue. In such a community, where families shared cramped quarters and mutual stairways in poorly built tenements, the only refuge was the taverns for both business and pleasure. But “the transaction of business,” says henry Grey Graham, was more the excuse than the reason for attendance.” Memoirs of Edinburgh citizens abound with stories of riotous debauch and headachy remorse. Most notable in this respect, perhaps, is James Boswell, whose diaries record innumerable instances of “jovial roaring” and morning after “squeamishness,” often cured with “old hock, which just cooled my fever and really sobered me.”

Boswell frequently chastised himself for his “hobbing and nobbing” , repeatedly vowing to be temperate in the future. But his good intentions were rarely more than that, and he seems to have shared the general Edinburgh attitude that intemperance was, at most, a “venial blemish.”

The favored drink of the literati was claret, but whiskey was not to be scoffed at. It was even celebrated in song by such poets as Robert Burns, who once declared that “freedom and whiskey gang thegither.” Burns liked to frequent a narrow room, known as “the coffin” , in John Dowie,s tavern, drinking with clerks and advocates during the day and men of letters at night. On his deathbed, it is said, Burns exclaimed: “O these Edinburgh gentles ( gentlemen ) – if it hadna been for them I had a constitution would have stood onything!”

Burns constitution lasted thirty-seven years. Others were not so lucky. Robert Fergusson, a gifted vernacular poet who extolled the common life of “Auld Reekie,” succumbed early. In 1773 he wrote “A Drink Ecologue” , a dialogue between a landlady, braandy, and whiskey, in which brandy describes itself as a “sweetly gusted cordial dose”. A year later, at the age of twenty-four, he was dead.

…”I’m reminded of a number of Muriel Spark novels where the same thing occurs – The Driver’s Seat, The Public Image, The Ballad of Peckham Rye. This last seems to owe most to Hogg, featuring a young Scottish man in a London suburb. He sports bumps on his forehead which he says are where his horns were sawn off, and causes all manner of devilment. The reader is never entirely sure if he is merely mischievous or has the whiff of sulphur about him. The ‘hero’ of Spark’s novel is called Dougal Douglas, and during an early scene the reader is told that ‘he changed his shape and became a professor’. Shape-changers belong to the world of folktales and ballads, and Spark was a great lover of Scottish ballads – just as Hogg avidly collected them for his friend Sir Walter Scott. In Justified Sinner Hogg even includes a lengthy anecdote relating to the appearance of Satan in the Fife town of Auchtermuchty. Masquerading as a preacher, Auld Nick is unmasked when someone lifts his vestments to reveal cloven feet beneath. When the Devil appears to Man, it is usually in some beguiling disguise.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS