“… There was a kind of cold-hearted selfishness on both sides, which mutually attracted them… they were neither of them quite enough in love to think that three hundred and fifty pounds a year would supply them with the comforts of life.” ( from Sense and Sensibility )

Jane Austen employs a very psychological approach, though whether this explains her enduring popularity in its entirety, can be substantiated and plausibly considered the subtext that elevates and distinguishes her work. She seems to be one of those who transmuted her suffering into art. A case for this was made in 1940 by D.W. Harding in F.R. Leavis’s literary magazine, Scrutiny. His essay was entitled: “Regulated hatred: An aspect of the work of Jane Austen.” Harding argued that far from being a calmly reassuring writer, Austen offers uncomfortable insights into society, and that her novels enabled her to attain “some mode of existence for her critical attitudes.”…

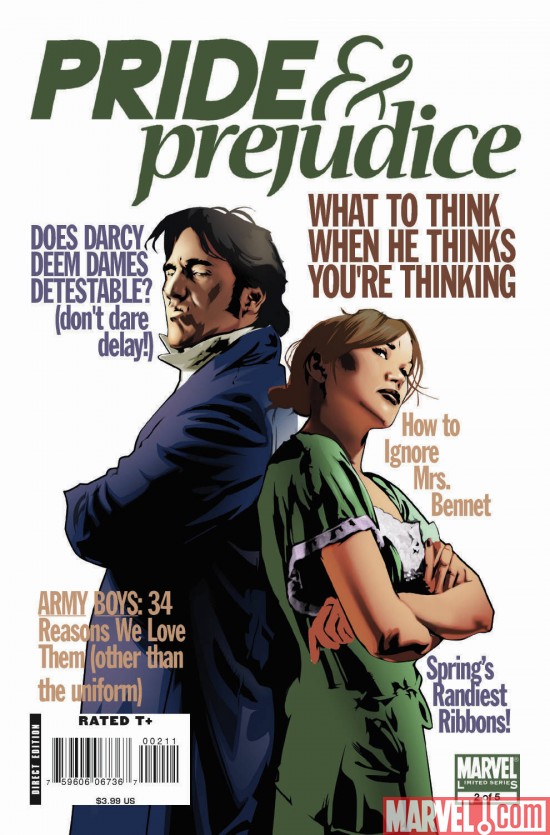

"...Austen's plot-engine in Pride and prejudice starts up with the question: "How can the eminently eligible Darcy have behaved so badly?" The elegance of the investigatory device is made psychologically profound, I think, by the tracing of how coming to love someone has little to do with the glance of a stranger across a room, but is itself a kind of investigation and explanation, a gradual coming to know the person."

Although the mating of couples in lawful wedlock is the stuff of which all Jane Austen’s novels feed, it is only in her last book,”Persuasion”, when her life’s strength was ebbing away and she was dying of cancer, that she allowed herself to release poetic lyricism. In her earlier books the reader is somehow miraculously made aware that the heroine is in love by innumerable indirect and minute hints whose significance grows on him almost as gradually as on the heroine herself. It may be objected that love between the sexes is not the only form of love; that there are other forms with which Jane Austen must have been more familiar.

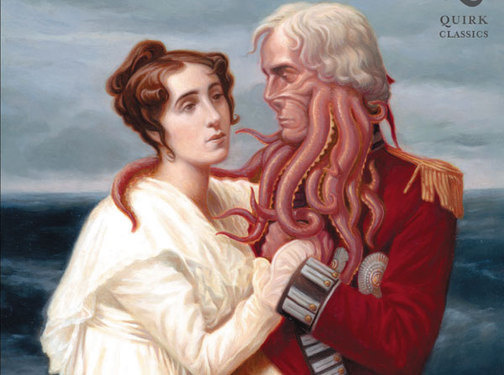

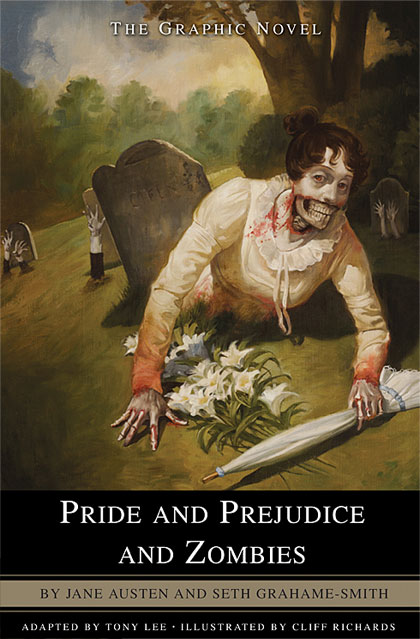

"It is a truth universally acknowledged that a Jane Austen novel in possession of added gore will be a surefire best-seller. That's the conclusion reached by publishers since the success of "Pride and Prejudice and Zombies," an unlikely literary sensation created by adding dollops of "ultraviolent zombie mayhem" to Austen's classic love story. "Zombies" – billed as 85 percent Austen's original text and 15 percent brand-new blood and guts – has become a best-seller since it was published earlier this year, with 750,000 copies in print. There's a movie in the works. And it has spawned a monster – or, more accurately, a slew of literary monster mash-ups."

Her entire life was spent with what seems to have been an exceptionally lovable and affectionate family. It is surprising , then, that in her novels pictures of family happiness are far rarer than the opposite: her characters’ affections for their relatives are highly selective. The friendship between Jane and Elizabeth Bennet in “Pride and Prejudice” is as perfect as that between Jane Austen and her sister Cassandra, but in the novel the two friends feel far from tender toward their younger sisters; Fanny Price, in “Mansfield Park”, is devoted to her dashing sailing brother William but regards her mother as a slattern and is ashamed of her father. As for Jane Austen’s attitude toward children, it has often been said that she disliked them. This accusation, based on a few quotations out of context, is extremely unfair, even though it is hardly a crime to dislike children. What Jane makes amply clear is that she dislike some children and all doting parents. But perhaps even more relevant to her psychology is her aversion to what she called “mothering”- that is, childbearing.

All Austen’s novels involve theory of mind. Readers need to attune to what characters may be feeling and thinking, even when clues are sparse. More especially, it seems to me that one of Austen’s pieces of deep originality was her invention of the novel of social explanation. It is generally acknowledged that the detective story entered literature with Edgar Allan Poe’s short-story “The murders in the rue Morgue” (1841) : A work based on the urge to discover and on explanation; and of course stories of this kind have remained immensely popular. But Austen was ahead of Poe with a story of gradual discovery and explanation: Pride and Prejudice (1813). Austen’s novel is a story not of forensic but of social explanation: why was the very eligble Mr Darcy rude to Elizabeth Bennet at a ball? There are, of course, innumerable puzzles in literature, for instance the question of how Oedipus could know who his mother was, or indeed how Tom Jones could know who his mother was. But these puzzles are different, and that it was Austen who conceived the novel based on social explanation.

Oatley:At an Edinburgh Festival, some years ago, I heard P.D. James talk about why the detective story holds such appeal. She said that the appeal is based on a wound having been inflicted on the body of society. By sheer cerebration, the detective works out not just who caused the wound, but what kind of person this was. With the conclusion of the investigation—in the fantasy, as it were, of the detective story—the wound is healed and life can continue. Austen, it seems to me, had a comparable insight. In Pride and prejudice she asks: "What kind of person, seemingly the very acme of gentlemanliness and eligibility, can have caused a social wound?" The wound is healed by investigation, explanation, and acknowledgement.

aThere can be no question that even though Jane Austen regarded married love as the greatest bliss on earth, she was aware that the price to be paid for it often exceeded the bliss itself. Families were large in those days, especially the families of clergymen- being poor she could hardly expect to marry anyone but a cleryman- and deaths from childbirth were common. To judge the effects of excessive “mothering” , she had but to observe her nearest acquaintances, her sisters-in-law, her nieces. To her niece Fanny Knight she wrote: “Do not be in a hurry ( to marry ) … by not beginning the business of Mothering quite so early in life, you will be young in Constitution, spirits, figure and countenance…”

Oatley:But, more helpfully than many other counter-arguers and precursor-offerers, you take the hypothesis forward. Perhaps, as you propose, Austen offers a more personally involving investigation than in Romeo and Juliet, in which, as you put it, we witness the characters rather than empathetically inhabiting their psychological states. And I agree, also, that in this Austen can be thought of as different from the writers of forensic stories of investigation, discovery, and explanation, such as Wilkie Collins, who came after her.

Even without mothering, Jane, who as a young woman was able to dance twenty dances at one ball without fatigue and still wish for more, was physically exhausted after twenty years of trying to take care of nieces and nephews while composing her books. Perhaps the burden of virginity seemed light to her compared to those of motherhood and conjugal duties. She was a tall, handsome girl, high spirited, and altogether desirable as a wife. And the fact that she was poor, or that one of her suitors died, cannot account quite satisfactorily for her never marrying, especiall

nce the horrors of the life of a penniless spinster were constantly present in her mind.

"...it seems that the theory of mind you mention might be a signal difference between Romeo & Juliet and Pride & Prejudice. We are not exactly asked to inhabit or infer the psychological states of Shakespeare's characters so much as to witness them (although this may well be a difference of medium). Perhaps Collins provides a useful case for this line of thought. Could you say that the reader is more of an external spectator to the investigation, discovery, and explanation for him, and more of an *embedded* spectator for Austen?"

No doubt if a man she could have loved truly and deeply had asked her to marry, she might have assumed the risks of mothering; but, without that, the advantages of being single and free at least to write books rather than cater to an indifferent husband and raise a brood of noisy children, outweighed any others.

it is a fallacy to believe that the mere accumulation of experience necessarily contributes to the development of a creative imagination. What matters is not how much experience a novelist has, but what they make of it. The question is asked: What is meant by an uneventful life? To those who have eyes and wit and understanding, the most trivial happenings can be events, while it is possible for others to spend their lives in the turmoil of great passions and high adventure without ever being aware if anything in the world save themselves.

"In life and print, therefore, we find mating behavior best explained by the genetically influenced method of mate selection that humans adopted in the Pleistocene era, the subject of evolutionary psychology. The rise of the novel, then, represents an expression not only of new ideologies of gender and marriage but also of universal desire explained by evolutionary psychology; nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in the most canonical of domestic novels, Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice."

Jane Austen, who was gifted with uncommonly observant eyes as well as enviable provisions of wit and understanding, never wrote a line about herself. None of her characters, be they principals or secondary figures, can be identified with any actual person. The elements of resemblance between her fictional characters and the real ones she knew, including herself, are sometimes striking to be sure, but they are mere elements, and the characters are genuine creations with lives of their own.

To achieve this transmutation of the drab raw material that everyday life offered to her into the sparkling human comedy that is the essence of her work requires more than wit or genius: it demands a peculiar blending of humility and ruthlessness. The humility is that needed to observe the unlimited variety of signs and symptoms by which even a minute and, to most observers, uninteresting sampling of humanity reveals the secret workings of mind and heart; the ruthlessness is that needed to rescue understanding from the pitfalls of maudlin sympathy.

(Richard W. Noland)..."attempts to respond to the clues that suggest why Emma avoids marriage throughout most of the novel. Her contention is that the novel is the story of Emma's discovery that she has a heart—a euphemism for sexual needs. She proceeds, with the help of psychoanalytic theory, to examine the way in which Emma's infantile narcissism and her sexual fear are gradually dispelled under the impact of reality, the stimulus of Emma's own honesty and self-awareness, and the abreactive effect of her effort to act out her fantasies. In Emma's case, the fantasy is essentially that she can control the world by planning other people's lives, especially their marriages. The essential movement of the novel, then, is from infantile narcissism and a posture of omnipotence, denial of instinctual needs, and adolescence to an emotional and psychological maturity as Emma discovers and acts on her love for Mr. Knightley—an act in accord with both psychic and external reality"

Jane Austen is as severe to her heroes as she is just to her unsympathetic characters. Mr. Bennet, one of the most lovable creations in all fiction, is nonetheless shown up in “Pride and Prejudice” as the irresponsible egoist that he is; and Mrs. Norris, the most detestable person in all of Jane Austen’s cast of characters, almost moves the reader to sympathy in the last pages of “Mansfield Park” , for her infuriating conduct is shown to be motivated by a pathetic yearning to be needed.

Jane Austen’s passion was for truth, and truth to her was comedy. This, of course, is a serious limitation: truth is not always amusing. Yet her few attempts to deal with more somber themes- Lady Susan and the unfinished novel, The Watsons- prove the wisdom of her self-imposed limitation. What she may be criticized for is not so much her decision to stick to comedy as her resolute determination to misunderstand the nature of tragedy, which she viewed either as a pose, comical in itself, or as the just reward for having strayed from the proper paths prescribed by “religious principles” and social decorum.

"Passive-aggression is an insidious form of tyranny that uses hypochondria and other tactics to manipulate. Presumably with her mother in mind, Jane Austen frequently portrays the passive-aggressive character and ridicules hypochondria, as in the satirical Sanditon. Mr. Woodhouse and Mrs. Churchill are life-denying parental figures in Emma, who use illness and hypochondria to manipulate their children, much like Mansfield Park's Lady Bertram, who uses hypochondria and social withdrawal to control her family. In Persuasion Mary Musgrove, a young copy of Lady Bertram, uses hypochondria and hysteria to manipulate, and Mrs. Clay passively ingratiates herself with the Elliot family in an attempt to become the next Lady Elliot. Through her novels Jane Austen shows the effects of this damaging, despotic behavior."

No one would have agreed more heartily than Jane Austen herself to the proposition that her novels are in some respects much thinner and more brittle fare than many a less perfect and more pretentious work of fiction.

ADDENDUM:

As Jane Austen says: “A family of ten children will always be called a fine family, were there are head and arms and legs enough for the number.” We must remember that reproduction is too often a vain repetition. Why repeat, until we find something worth while? Indeed, I would almost say that a woman had no business to be a mother until she can demonstrate her ability to be something else. ( Kate Gordon )

FROM EMMA:

While he spoke, Emma’s mind was most busy, and, with all the wonderful velocity of thought, had been able–and yet without losing a word– to catch and comprehend the exact truth of the whole; to see that Harriet’s hopes had been entirely groundless, a mistake, a delusion, as complete a delusion as any of her own–that Harriet was nothing; that she was every thing herself; that what she had been saying relative to Harriet had been all taken as the language of her own feelings; and that her agitation, her doubts, her reluctance, her discouragement, had been all received as discouragement from herself.–And not only was there time for these convictions, with all their glow of attendant happiness; there was time also to rejoice that Harriet’s secret had not escaped her, and to resolve that it need not, and should not.–It was all the service she could now render her poor friend; for as to any of that heroism of sentiment which might have prompted her to entreat him to transfer his affection from herself to Harriet, as infinitely the most worthy of the two– or even the more simple sublimity of resolving to refuse him at once and for ever, without vouchsafing any motive, because he could not marry them both, Emma had it not.

She felt for Harriet, with pain and with contrition; but no flight of generosity run mad, opposing all that could be probable or reasonable, entered her brain. She had led her friend astray, and it would be a reproach to her for ever; but her judgment was as strong as her feelings, and as strong as it had ever been before, in reprobating any such alliance for him, as most unequal and degrading. Her way was clear, though not quite smooth.–She spoke then, on being so entreated.– What did she say?–Just what she ought, of course. A lady always does.– She said enough to shew there need not be despair–and to invite him to say more himself.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS