“Adah Menken was the most remarkable mingling of angel and devil that ever wore petticoats.”

She invented the modern cult of female celebrity. Her goal, originally, was to be famous based on talent. To be recognized as the outstanding actress in Shakespearean roles in America, somewhat modeled on the role of Sarah Siddons or Edmund Kean in England, who had also risen from relative obscurity. But Menken’s encounters with the bard were disastrous: in a performance in Nashville she had been hooted from the boards, and one critic described her acting as “dumb stricken” . At the time, James E. Murdoch, a veteran Shakespearan actor who had played the Thane to her Lady Macbeth, gave her a piece of advice that she had not adopted, but had not forgotten. Speaking guardedly, for Menken was notorious for her explosive temper, Murdoch advised her to leave Shakespeare alone.

"I have long been a student of sculpture," Menken replied, "and my attitudes, selected from the works of Canova, present a classicality which has invariably been recognized by the foremost of American critics."

“Because you are more suited to sensational spectacle… There your fine figure and pretty face will show to the same advantage as the proseprous curves of Madame Celeste.” Madame Celeste was a French entertainer whose fame rested on dressing in tights and performing gymnastics, and so Menken had flown into rage at the idea. For someone who aspired to wear the crown of Rachel, it was unthinkable to wear the tights of Madame Celeste. However, she had remembered Murdoch’s advice and now agreed to act in Mazeppa. The horse fell during the rehearsal, and Menken injured her shoulder. She staggered dramatically to her feet and intoned: “I will not show the white feather!”

Once again Menken was lashed onto the horse’s back . Upon cue the mare proceeded up the runway, and Adah Isaacs Menken was carried to fame. It was the first of a thousand and more perilous trips she would make up similar inclines. She had never seen Mazeppa produced, nor had she read the script, but that did not matter too much. Conquering the horse, not the lines was the biggest obstacle. Wearing flesh colored tights and a bit of drapery, she was indeed strapped to the horse to the amazement of all. Indeed, it was the origin of the sobriquet “The Naked Lady” , which was attached to Menken as long as she lived. The crowd went wild. A New York newspaper was to put it more subtly: “The Menken is without a rival in her special line, but it is not a clothes-line.”

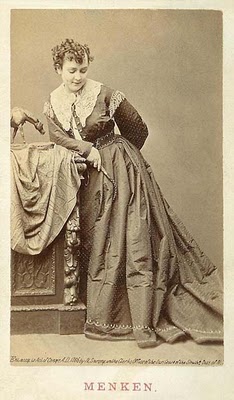

Napoleon Sarony photograph. According to Dante Gabriel Rosetti, someone wagered Menken one hundred pounds that she could not seduce Swinburne; and Menken, failing for once, lost the bet. After working tirelessly on the project for six months, she said morosely,"I can't make Algeron understand that biting's no use."-Marberry

Journalists followed James and a liveried servant into Menken’s suite, the most expensive in Albany. Not one scribbler regretted the tedious trip after Menken, reclining on a tiger skin, showed her much vaunted muscular legs. She sipped champagne in between feeding bon bons to a French poodle. The petit bombshell, fancied herself the successor to Lola Montez whom she surpassed in popularity. In homage to Lola, Menken choreographed a “spider dance” based on the scandalous shimmy her mentor brought down the house with. Spiritually speaking, she asserted she was the spiritual descendent of Goethe.

--- If provoked, she fired rockets like, “Good women are rarely clever and clever women are rarely good.”---

Adah Isaacs Menken (183?-1868) was an author and an actress whose constructions of identity result in a figure who has been customarily explained as both a transgressive force in a domestic economy, as well as a deviant sexual aberration . Her elusively gendered public presence and performances confounded the critical descriptions of her contemporaries and have proven a difficult subject ….(Barca) Her ambiguous and mysterious origins add to the suggestion of a labyrinth of paradoxes that seem unique to American culture. As Melville said in “The Confidence Man” , “Life is a picnic en costume; one must take part, assume a character, stand ready in a sensible way to play the fool.” A masked nobody can be anybody.

Menken was a controversial American actress and poet who was a brilliant self-publicist being one of the first to see the promotional potential of photographs in her campaign to make herself famous. She was particularly keen to be photographed with famous literary figures of the day and in risqué attire. The public was shocked in the 1860s with Menken’s short hair and even shorter skirts, and she once gave a press conference lying on a tiger skin, sipping champagne, and smoking a cigarette. Defying conventional values with shocking behavior was her key to fame and fortune rather than acting ability. Her most famous stage role was that of Mazeppa in which she was strapped to a horse in flesh-colored tights seemingly nude. In fact, removing her cloak in one role she has been said to have performed the first public striptease act ever witnessed in a theater. She may also have been the first woman in American theater to bare her legs.

1863. Foste

oadway began in Albany, New York inJune 1861. Opening night the audience at the Green Street theater gasped as Adah Isaacs Menken catapulted to the theatrical heavens on the back of a wild steed. Mazeppa, a popular equestrian drama based on Lord Bryon’s epic poem, brought her instant stardom On this opening night, John Smith, a theatrical impresario, placed his bet on the violet-eyed beauty whose scandalous personal life kept the Victorian tabloids in copy.

So goodbye yellow brick road

Where the dogs of society howl

You can’t plant me in your penthouse

I’m going back to my plough

Back to the howling old owl in the woods

Hunting the horny back toad

Oh I’ve finally decided my future lies

Beyond the yellow brick road …

Each Menken persona succeeded in obliterating the next. For a time she lived as a romantic poet, a female Byron. Briefly, she made a good Jewish wife in the midwest, before becoming the consort of an Irish boxing champion among the gangs of New York. Down and out, she presently became the rage of San Francisco, throwing over he wimpy fourth husband for a Rhett Butler style gambler who may have been a confederate agent. In the capitals of Europe Adah achieved spectacular success and was both worshipped and vilified; the public needs a goddess if only to sacrifice. The transition from one of Adah’s selves to the next could be violent; but no one living, including Adah’s closest confidant, could have answered the question: Who was she?

Horace Vernet 1827. "Mazeppa was based on a play by Lord Byron, and tells the saga of a Ukranian man who falls in love with a married countess. Upon discovery of the illicit affair, the Ukranian man is punished for his adultery by being strapped naked to the back of a galloping horse. This poem was a popular stage production, but but when it came to the climactic riding scene, the standard of the day was to attach a fabric mannequin to a live horse, so as to not offend the genteel theater viewing public. Menken would perform the role of Mazeppa – a role originally written for a man. This was not unusual for the actress – she performed many cross-gender roles on stage, to the delight of her many fans. But for Mazeppa, things would be different. During rehearsals for Mazeppa, Menken wanted to take her role as far as she could. Not satisfied with having a naked dummy representing her on the back of a wild horse, Menken wanted to be strapped to the horse – wearing nothing but flesh-colored tights and leggings, to give the appearance of nakedness."

She deliberately fashioned herself into a Jewish female poet and prophet, a sexually powerful woman, a powerless female victim, a sexually ambiguous cross-dresser, a bohemian outcast, an androgynous tragic hero, an international star, and a fallen star. Although these public masks make it difficult to find the “real” Menken, Sentilles’s study of these various personae reveals a great deal about the culture, about the preconceptions, obsessions, and changes in Civil-War-era audiences. In short, “Menken was the performance,” and Menken the performance turns out to be “far more historically illuminating” than Menken the person. She was a cultural outsider on a quest for what America meant to her and was at the crossroad of what constitutes amusement and what constitutes art and in so doing touches something deeply resonating in American culture; Menken’s life proved to be a nuanced assessment of a country whose virtues and conflicts seemed to commingle magically. She was like a riverboat gambler, a loner who wisely concealed her hand , lending an aura of ambiguity and doubt: She wore a mask and had an ambiguous role in American culture.

History is a social science that demands evidence for its claims, but what happens when the evidence itself is unstable, unreliable and untrustworthy. All the tracks have vanished, and like much of American myth, there is ambiguity and doubt. Adah Isaacs Menken was a Civil War era celebrity who relied on rumor and hearsay to keep her popularity alive. Indeed, one can say that hearsay from the nineteenth-century has led to a resurgence of interest in her in the twenty-first. ….If one looks Adah Isaacs Menken up on the Internet, she will appear as an African-American poet, a Jewish poet, a lesbian cross-dresser, and a salacious nineteenth- century sex symbol, but only one of those images was familiar to Menken’s own public. Can rumor be historicized? Does examining hearsay undermine what history purports to do, or does it allow us to address topics otherwise left in the margins? This program will address these questions while examining the life of one of the most fascinating people in American history. ( Renee Sentilles )

Foster: ( Edwin) James, the archetypal press agent, knew how to play on the panting journalists’ erotic fantasies; for starters, he provided free drinks all around. James knew that a star, like other saleable commodities benefited from hype—not that the ambitious Menken needed help to generate her own publicity. She bobbed her hair, smoked cigars, and wore pants in public and published risqué poetry rife with clues to her lurid love life.

What do you think you’ll do then

I bet that’ll shoot down your plane

It’ll take you a couple of vodka and tonics

To set you on your feet again

Maybe you’ll get a replacement

There’s plenty like me to be found

Mongrels who ain’t got a penny

Sniffing for tidbits like you on the ground

Foster:Menken’s theatrical innovations, too, are still with us. However, she did not originate the “girlie show”. Menken’s act was solo and dangerous. Nudity in Mazeppa ends after the first act. The Menken persona was sexually ambiguous, much like Marlene Dietrich: one moment the epitome of sexuality in a low cut gown, the next dressed in a tuxedo smoking a cigar. This sort of allure transcends gender or nationality.

ADDENDUM:

Foster:

Adah retreated to Jersey City where she attempted suicide. An unknown friend, possibly Walt Whitman, found her in time and saved her. In 1860, Adah assuaged her heartache by writing her most gut wrenching poetry. Erica Jong, in a review she wrote of Sylvia Plath’s Correspondence in November 1975, pointed out that “Sylvia Plath’s poetry was the first poetry by a woman to fully express the female rage.” Interestingly, Menken raged more than a century before Plath. Moods of despair alternated with defiant ones. In Judith, published in September 1860 in the Sunday Mercury, Menken blasted Heenan in a Biblical context.

Foster:Arthur Conan Doyle’s gripping Scandal in Bohemia features a lead character, Irene Adler, based on Menken. Scandal in Bohemiawas the first Conan Doyle story to gain popularity, a prelude to his classic Sherlock Holmes mystery stories. In Scandal in Bohemia, Watson reveals: “To Sherlock Holmes she (Menken-Irene Adler) is always the woman. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex.”

Menken assumed the role of a vengeful Judith lusting for the head of Holofernes. She imagined Heenan’s “long black hair clinging to the glazed eyes . . . The strong throat all hot and reeking with blood.” The same year the Mercury also published Menken’s bold essay in defense of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Menken lashed out at detractors who condemned Whitman’s “barbaric yawp.” In her Swimming Against the Current, she trumpeted the poet “centuries ahead of his contemporaries” . . . who “wields his pen, exerts his energies for the cause of liberty and humanity.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS