Like Dickens and Balzac, he wrote because he could not help writing, but he did not think that the chief business of life was to be put into literature; and much as he appreciated his contemporary fame, he does not appear to have cared a fig for immortality.

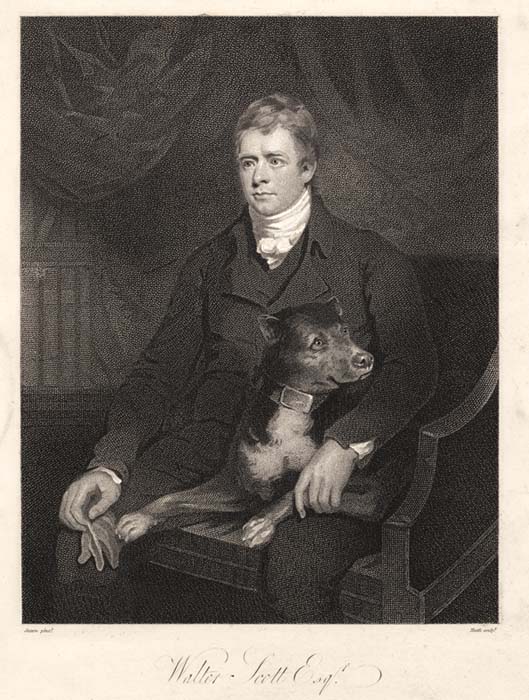

In 1970, Edgar Johnson published a two volume life of Sir Walter Scott, “The Great Unknown”, 1279 pages of text that traced his extraordinary career from day to day, without omitting a dinner party, which served to remind us of his once enormous popularity with readers all over the world. Though some of his best known works, “Ivanhoe” and “The Talisman” seem more like advanced children’s books, Scott also wrote homelier novels, realistic in their psychology, about the manners of his countrymen, and most of these Scottish books, have retained an appeal to more sophisticated readers.

Hazlitt: His is a mind brooding over antiquity -- scorning 'the present ignorant time.' He is laudator temporis acti "prophesier of things past." The old world is to him a crowded map; the new one a dull, hateful blank. He dotes on all well-authenticated superstitions; he shudders at the shadow of innovation. His retentiveness of memory, his accumulated weight of interested prejudice or romantic association have overlaid his other faculties. The cells of his memory are vast, various, full even to bursting with life and motion; his speculative understanding is empty, flaccid, poor, and dead.

Balzac: Scott’s chief and splendid claim to originality is that he was the first novelist to relate man to the circumstances and traditions, political, social, religious and natural of the society in which he lives….

One of his more interesting novels, the one with the most dramatic story and the fewest trappings of romance, is “The Heart of Midlothian”.The novel is based loosely on the heroic walk to London by Helen Walker of Irongray in Dumfriesshire, who, in attempting to enlist the support of the Duke of Argyle in obtaining a pardon for her sister on the charge of child-murder, served as the basis for Jeanie Deans. She is, unlike so many heroines of novels of the period, severe, active, and dominating. The climax, winning her sister’s life from Queen Caroline, is a vindication of her four-square, practical philosophy and personal determination.

Hazlitt:The Author of Waverley wears the palm of legendary lore alone. Sir Walter may, indeed, surfeit us: his imitators make us sick! It may be asked, it has been asked, 'Have we no materials for romance in England? Must we look to Scotland for a supply of whatever is original and striking in this kind?' And we answer 'Yes!' Every foot of soil is with us worked up: nearly every movement of the social machine is calculable. We have no room left for violent catastrophes, for grotesque quaintnesses, for wizard spells. The last skirts of ignorance and,barbarism are seen hovering (in Sir Walter's pages) over the Border. We have, it is true, gipsies in this country as well as at the Cairn of Derncleugh: but they live under clipped hedges and repose in camp-beds, and do not perch on crags, like eagles, or take shelter, like sea-mews, in basaltic subterranean caverns. We have heaths with rude heaps of stones upon them: but no existing superstition converts them into the Geese of Micklestane-Moor, or sees a Black Dwarf groping among them.

It starts in the year 1736. A mob has set fire to the solid oak door of the Edinburgh prison, or tolbooth, known as the very heart of the shire of Midlothian. Inside the prison is Jock Porteous, once captain of the city guard, then condemned to death for having ordered his guardsmen to fire on a not very menacing crowd of burghers. He has been reprieved by Queen Caroline, but now the mob is about to seize and lynch him.

Another prisoner is young Effie Deans, the wayward daughter of a dairyman, or “cow feeder” who is soon to be tried for her life under a stern Scottish law. Since Effie has borne a child in secret and the child has disappeared, she is presumed guilty of murder. “Flee, Effie, flee!” says Geordie Robertson, the leader of the mob, who is Effie’s outlawed lover. She refuses to stir from the strong room of the prison. “Better lose life,” she murmurs, “since lost is god fame.” Geordie is called away to lead Porteous to the gallows. Then the mob disperses quietly, after leaving behind a guinea to pay for the rope that hanged him.

At Effie’s trial a few weeks later, the decisive question is whether she concealed her pregnancy. If she confessed it to anyone- even to her older sister, Jeanie, the heroine of the novel- she will not be executed. The truth is that she had confessed it to no one, but Jeanie can save her by telling a white lie. Jeanie bears no resemblance to Scott’s other more romantic heroines. ” She was short,” he says of her, “and rather too stoutly made for her size, had grey eyes, light-colored hair, a round good-humored face much tanned with the sun, and her only peculiar charm was an air of inexpressive serenity.” owed to a good conscience.

"There has been a strong tendency among novelists of the present century who have written since Scott, to devote themselves more to the common characters and incidents of every-day life; to describe the world as it appears to the ordinary observer, who rarely associates with either heroes or villains, and has little experience of either the sublime or the marvellous."

In the trial scene that is the climax of the novel, Jeanie refuses to perjure herself. Nevertheless, she is determined to save her sister, and after Effie has been sentenced to death, Jeanie sets out to London to plead for a pardo

he walks barefoot until she crosses the English border; then she puts on shoes and stockings for the honor of Scotland. In the course of an adventurous journey she is befriended by innkeepers, abducted by highwaymen, and released by a crazy woman. Jeanie also learns that Geordie Robertson, the outlaw, is really George Staunton, the heir of an English baronet.

When she reaches London, the great Duke of Argyle receives her as a compatriot and btains for her a private audience with Queen Caroline. It soon transpires that the queen was outraged by the hanging of Captain Porteous after she had given him a reprieve, but Jennie goes on with her plea for mercy. …

“Arrived in London, she appeals with simple forthrightness to the Duke and the Queen Caroline. Through the Duke’s benevolence, Jeanie is able to marry her fiancé, the Presbyterian minister Reuben Butler; her father is retired to a farm on the Duke’s estate; and Effie marries her lover, Staunton. The infant she was accused of murdering is, in fact, still alive, sold by Meg Murdockson to a vagrant woman in revenge for Staunton’s having seduced her insane daughter, Madge Wildfire. Ironically, at the close of the novel, like Laius in Greek myth Staunton is slain by his own son on the highway.”

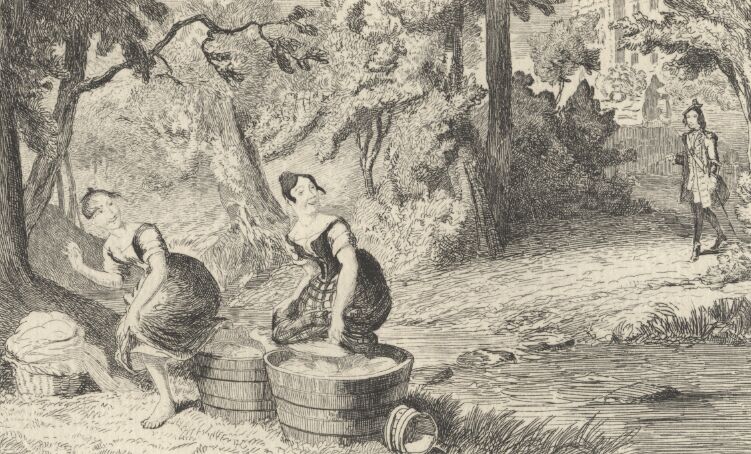

Waverly Illustration. George Cruickshank. "Previous to the publication of "Waverley," Scotland was a comparatively unknown land. Even Englishmen had little knowledge of its national habits, of its traditions, or its scenery. To Scotchmen, the history of their country was little more than a skeleton, till the magic wand of Scott it filled it with flesh and blood, and gave it new life and animation."

… In the fourth and final volume of the novel, Jeanie goes back to Scotland in the Duke of Argyle’s calash. She has a happy reunion with her suitor, the penniless clergyman, whom the duke is about to install in a comfortable parish. Her years will now be spent as a happy housewife and mother. Effie, after learning fashionable manners in a French convent, appears in London society as the great Lady Staunton, She is, however, childless and disconsolate and still hopes to find the son who was spirited away from her a few hours after his birth. He is rumored to be hiding near Reuben Butler’s parish, where Sir George goes to look for him. But the lost son has become an outlaw, as Geordie Robertson had been, and during a robbery attempt, he kills his father. Lady Staunton retires to a convent.

“READER-” Scott says with what must have been a sense of dogged achievement,

“This tale shall not be told in vain, if it shall be found to illustrate the great truth that guilt, though it may attain temporal splendour, can never confer real happiness; that the evil consequences of our crimes long survive their commission, and, like the ghosts of the murdered, for ever haunt the steps of the malefactor; and the paths of virtue, though seldom those of worldly greatness, are always those of pleasantness and peace.”

"Delacroix’s The Abduction of Rebecca (above, from 1846), which shows a scene from Sir Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe falls right into Delacroix’s sweet spot. Scott has two Saracen slaves of the Christian knight who has lusted for Rebecca carry the beauty off on horseback. "Delacroix was passionately in love with passion,” Charles Baudelaire once wrote, “but coldly determined to express passion as clearly as possible." Despite the amazing contrasts of light and dark, motionlessness and action, color and colorlessness in this painting, Delacroix keeps it all together in a neat package full of meaning without overflowing into chaos."

Those final lines, like a preacher’s benediction, went off to the printer at the beginning of July, 1818. After calculating that “Midlothian” would pay off his debts, Scott had borrowed money to buy another broad tract of land near Abbotsford- “which makes me a great laird,” he said. He admitted grandly that he wrote for money. He wanted to live like a great nobleman, without counting the shillings, and the emolument he won by his unremitting toil was always spent before he even earned it. For each of his novels he demanded a very large payment in advance, usually more than the publisher had cash to offer. He was therefore given promissory notes for six, twelve and eighteen months, which he promptly had discounted at an Edinburgh bank. That involved a risk; if the publisher failed to meet payment on the notes, Scott himself would have to make them good: …

By the beginning of 1826, in spite of his unprecedented success, Scott’s investments in Ballantynes, an Edinburgh publishing and printing firm, had caused him deep financial embarrassment. The firm collapsed with debts of 130,000. By this time Scott was the only partner with a financial interest, and was forced to enter a composition with his creditors which allowed him to continue to occupy his country seat, Abbotsford, the intention being that he should repay his debts through his writing, which he was determined to do as a matter of honor. The effort worsened his already failing health, but the debts were paid off not long after his death in 1832 [Anderson, 1971].

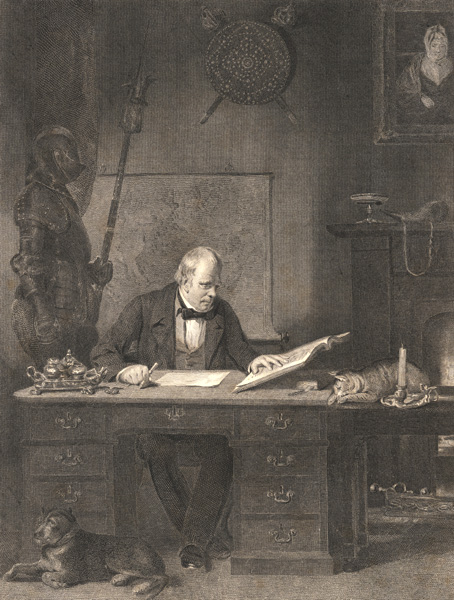

Artwork David Wilkie. "Scott, Dickens, almost all the great English novelists described heroes and heroines. They made their chief character an embodiment of virtue or strength, and strove to win for him the admiration of the reader. Even Tom Jones was a hero to Fielding, and Roderick Random to Smollett. But Thackeray said to himself as he looked out on the world, that humanity was not made up of heroes and villains. He had never met with the truly heroic, nor with the utterly depraved. It seemed to him that human nature lay between the two extremes."

… Offers came pouring in, but Scott refused them all, just as he had already refused to evade his creditors by going into bankruptcy. He was determined to repay the enormous debt by his own writing. “Unless i die,” he wrote Lockhart, ” I will beat up against this foul weather- a penny I will not borrow.” During the half dozen years that remained to him, Scott published an amazing number of books, besides a quantity of miscellaneous journalism that would have kept an ordinary writer busy; this last was written in what might have been his idle moments. Scott was writing himself to death.

His right hand failed him in the winter of 1830, when he suffered a paralytic stroke, the first of a series, and his last books had to be dictated to secretaries. Plainly inferior as they were to his earlier work, the public continued to read them. Before he died, in September 1832, Scott had earned vastly more than any other author before him, in any nation, and had paid most of his debt. The rest of it was paid in full, twenty years later, by the sale of copyrights to his new publisher, Robert Cadell, who became a very rich man as a result of the transaction.

Today, Scott has probably fewer admirers than other nineteenth-century giants; his work is less discussed than that of Jane Austen, Dickens, the Bronte sisters, George Eliot, or Henry James. Beyond his feudal tales of chivalry and knights in armor, he was however, a man of the new age: a reckless enterpriser allied with the middle-classes and, on a deeper level, with the Scottish peasantry.It is this democratic and more realistic side of his work that can be relished today, and this is best shown in “The Heart of Midlothian”.

Not only is the heroine a cow feeder’s daughter, but most of the persons she meets are innkeepers, lawyers, highwaymen, small lairds, all portrayed with affection and with Scott’s keen eye for the grotesque in everyday life. The reader thinks of Dickens, and it is true that Scott has the same gift for vilifying any character from low life that he touches even briefly. He is not as good as Dickens at his best, but he is better at characters from high life, such as Queen Caroline and the Duke of Argyle, and better too, at telling a headlong story.

ADDENDUM:

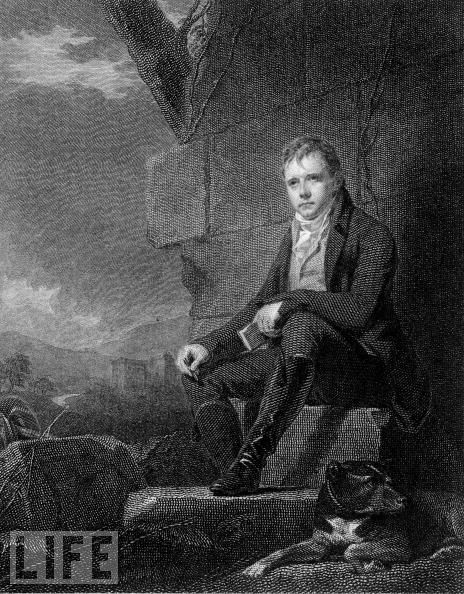

Robert Speaight: Scott’s poetry is not to be despised; for T. S. Eliot it supplied a yardstick by which to measure the more considerable achievement of Byron. In On Poetry and Poets Eliot discerned in busts of the two poets a certain resemblance in the shape of the head : The comparison does honour to Byron, and when you examine the two faces there is no further resemblance. Were one a person who liked to have busts about, a bust of Scott would be something one could live with. There is an air of nobility about that head, an air of magnanimity, and of that inner and perhaps unconscious serenity that belongs to great writers who are also great men. But Byron — that pudgy face suggesting a tendency to corpulence, that weakly sensual mouth;that restless triviality of expression; and worst of all that blind look of the self-conscious beauty ; the bust of Byron is that of a man who was every inch the touring tragedian.

We might have expected Eliot to recognize greatness in the character of Scott — more important things apart, both men were Tories in a sense that the average Tory of today would hardly understand i f you explained it to him. But it is gratifying that he also recognized greatness in Scott as a writer, and one wishes that he had devoted an essay to him. He might not, however, have agreed with Lockhart and Southey and Byron and many of Scott’s contemporaries in saluting him as a great poet. Scott was a skilful, inventive and tireless versifier, but he held his own poetry of small account. ‘Byron,’ he admitted, ‘hits the mark where I don’t even pretend to fledge my arrow’; and with Childe Harold he had ‘bet him out of the field’ — a field to which he only occasionally returned.

…( James Fenimore )Coopers assimilation of Scott is however, most clear in his descriptions of nature and his dramatization of the westward movement against the American frontier and the harm that civilization brings with it in the wake of progress. Both authors promote the idea of stadialism. Stadialist theory postulates that historical movement of civilization progresses through a series of stages from savage, barbarian, pastoral and ultimately to civilized. The changes in these stages are marked by the technique of subsistence used by a culture such as hunting, herding, farming, commerce and industry.

We see stadialism used by Scott as he moves his characters north and south. The civilized south comes into conflict with the more rugged and pastoral highlands of northern Scotland. We see the characters of the highlanders portrayed in similar fashion to the Native Americans of Coopers novels. Scott sets the Scottish Highlands as completely removed from the readers more urban environment and portrays the northern clans as if they are noble barbarians, who live with the land but are consequently in conflict with the encroachment of urban and more civilized settlements from the southern regions of Britain. Scott uses this cultural conflict to dramatize the political dissent of his time as the “savage” northern invaders tread upon the soil of the “civilized” south, and to polarize the contrast between the two regions and its inhabitants.

In Scott’s work, progress and romance can only be achieved by the steady movement north. The civilized characters travel through a historical and geographical change that can only be experienced by someone from a more urban setting transported out of their natural environment.

Cooper seems at first to follow the same theme, replacing Scott’s north south conflict with the steady western movement of civilization from the eastern seaboard of the United States. We are witness to the same noble efforts of the wild inhabitants to deal with the encroachment of civilization. Cooper is clearly fond of the wilderness of America and goes into great detail about the landscape and the nature of the men that choose it above the growing urbanization of the cities.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS