The search for myth, for universal patterns is necessarily a search for the meaning of modern life. Or, it can be viewed as an attempt to escape from it. At this point Harlan Ellison’s quest becomes perilous and paradoxical in that one mode of truth can be traded for another. This form of romanticism takes the form of a uniquely modern search for myth and original archetype as a vital reaction to a world in which objects have become increasingly opaque; unresponsive to man’s need to interact on deeper levels with his surroundings. Ellison’s mythical imagination is impelled and compelled by the same wants…

It got up that afternoon–walked to the door with its paw on the south wall to

steady its trembling body

Let out a soul-rending creak from the bottomless roof of his mouth

thundering from my floor to heaven heavier than a volcano at night in

Mexico

Pushed the door open and said in a gravelly voice “Not this time Baby–

but I will be back again.”

Lion that eats my mind now for a decade knowing only your hunger

Not the bliss of your satisfaction O roar of the universe how am I chosen

In this life I have heard your promise I am ready to die I have served

Your starved and ancient Presence O Lord I wait in my room at your

Mercy. ( Allen Ginsberg, The Lion for Real )

“When I’m gone, that’s it,” he said. “What’s down on the paper, it says ‘The End,’ that’s it. ‘Cause right now I’m busy writing the end of the longest story I’ve ever written, which is me.”

…In his writing, style and opinions are both personal and highly emotional. The voice speaking to us seems almost intent on physical contact, on abolishing the indifference of the printed page that normally separates reader from writer. the flourishes of what appears to be unbridled egomania struggling to break free of convention is fascinating as well. But even more interesting, and central to the author’s intentions is Harlan Ellison’s use of this commenting voice as a literary device. The person who speaks to us with increasing insistence from the prefaces and margins of the work is not the real “Ellison” but a persona, an actor himself in the drama of literary creation…

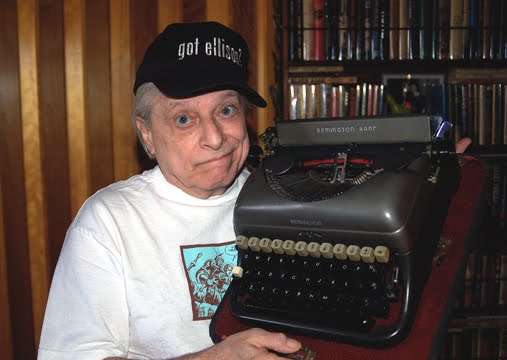

There is a plausible argument that it is some of the best American writing to be put on paper; and he would prefer you didn’t call it science fiction. Is is writing a matter of conscience? As M.L. King said, ” Our life begins to end on the day we become silent on the things that matter”. He is a 76-year-old literary lion, with an undisclosed illness, shrunken weight, but still capable of a mighty roar. Quiet he is not. In fact, he’s the opposite: A loud and highly opinionated guy with a history of pulling stunts and creating a stink . Above all, he’s a writer devoted to his craft.

"However, the film doesn't touch on many of the controversies surrounding him, barely mentioning two of his many lawsuits, the fact that he was fired from Disney on his first day on the job, or the controversial boob-grabbing during the World Science Fiction Convention two years ago. In fact, the hardest line of questioning comes from Robin Williams at the beginning of the film, who runs through a laundry list asking Harlan if some of the things he is credited with doing are true or not."

…Harlan Ellison is never studied seriously because fantasy as a literary genre, is more or less marginalized and ignored. It is low brow and in the ghetto of mainstream tastes; the opposite of what Dickens referred to as “the purity of the middle class”. But, this non-mainstream kind of tale spinning that Ellison writes was done not only by Poe, but by Hawthorne, Melville, and Mark Twain as well; mythical allegories which explore the mind and soul of a nation without a long cultural tradition or firm landmarks. Ellison belongs in this genuine mainstream…

“Ellison, an energetic and controversial writer who penned hundreds of short stories and novels, as well as the unforgettable Star Trek episode “The City on the Edge of Forever,” also told the publication that he’s finished his last book — and issued orders for his wife to burn any unfinished manuscripts the instant he dies. “When I’m gone, that’s it,” he said. “What’s down on the paper, it says ‘The End,’ that’s it. ‘Cause right now I’m busy writing the end of the longest story I’ve ever written, which is me.” ( Lewis Wallace )

…At the center of each of Ellison’s tales is the same elemental confrontation between man and the forces that animate his universe. It is however, of a unique and violent sort filled with lots of Biblical style blood, gore, shock and awe, though the aggression is rarely gratuitous, as if following a chaotic yet coherent pattern. It is all part and package of the human condition as Ellison sees it, as if god decided to trash the joint instead of resting on the seventh day. At times, his vision of man’s fate seems darkly pessimistic: a bleak appraisal like Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. Ellison does fall into the pattern of a survival of the fittest, a hunkering down in a universe both violent and cruelly indifferent….

Its called speculative fiction, or fantastic fiction. The output is simply staggering. His two anthologies Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions–a projected third has never appeared–were crucial to the American New Wave by providing a market in which it was possible to say things about sex and politics, and in ways that varied from stylised fabulism to the radically deranged, that could not be said in the SF magazines of the 1960s. His own idiosyncratic short stories are true to the same aesthetic values as his editing–absolute emotional honesty conveyed by any means neccessary. Some of them deal with stock sf themes like the mad computer that tortures throughout eternity the last survivors of humanity–‘I have no mouth and I must scream’–or dystopia–‘Repent, Harlequin, said the Ticktock Man'; other dramatize philosophical themes like the Death of God–‘Deathbird'; while others engage semi-confessionally with the

emmas of the contemporary male writer–‘All the Lies that are My Life.’

Lauren Davis:In 1994, Ellison, inspired by Yerka’s work collaborated with the painter on Mind Fields. Yerka created 34 paintings for the book, and Ellison wrote a short piece of fiction for each painting, latching onto images or themes he saw in them. The piece above, entitled “Fever,” inspired a story which begins: Icarus did not die in the fall. What his father, Daedalus, never saw was this: Icarus fell toward the Aegean Sea; fell through clouds; through billos and canopies and flotillas of clouds; and was lost to the sight of his father. The wings melted and fell away. They were carried on the stratospheric currents, miles away from the drop point at which Icarus had vanished through the cloud foam....

… But Ellison manages to sidestep some of the standard reductionism of post-Darwinian determinism by elevating the rhetoric to a sort of pseudo-quasi-spiritual level: Battles in Ellison are fought on a strangely intimate and personal level as if he is constantly auditioning for the role of prophet. There is in fact, something very much akin to the Old Testament view of the relationship of man to a harsh god or deities in the plural. The horrible, nearly sadistic torments copiously heaped onto these protagonists are of the Abraham and Isaac variety, Joseph, and the Exodus rolled into a common refrain of what could they have possibly done to warrant their fate. Yet, these victims can and do, from the depths of their fear and trembling, draw the strength to rebel….

Harlan was born in 1934. His first real typewriter was a Remington noiseless portable, circa 1936-1940. In 1949, Harlan’s father died, and Harlan and his mother moved from Painesville to Cleveland, Ohio. Harlan’s mother worked at the B’nai B’rith second-hand resale thrift shop, and Harlan had three jobs, because they were broke. This is not a sob story; it is no different than the stories each of you can tell. It is merely background history. Harlan’s Mother, Serita Ellison, encouraged her son’s writing enthusiasm, and his love of science fiction, and sometime between 1949 and 1951, she bought for an unknown sum, the Remington portable noted above. At the thrift shop. And she brought it home to Harlan. You know what happened from then until now. The books, the stories, the tv shows, the movies, the spoken word albums, the adventures…the misadventures.

…Like the heroes of the Old Testament, they are “the chosen people” singled out of the mass of man by some fiery and erratic finger, pressed and harmed, until in spite of their flaws, rise in anger and challenge their tormentor. The Hebrews demanded a personal relationship with their maker; whether ‘chutzpah” delusional ego, or valid claim, they pay dearly for their perceived right. To Ellison, the worst gods of all are the system builders- the descendants of Blake’s Urizon. Ellison’s heroes fight their oppressors; drawing on heretofore unrecognized reserves of strength, they can even overcome, making themselves into gods in turn, and oppressing others in kind. …

Harlan Ellison is most often associated with science fiction. That’s understandable, of course. He is the author of some of the greatest science fiction stories ever written, like “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman” (1965) and “A Boy and His Dog” (the 1969 short story made into a film in 1974). He also wrote legendary screenplays like the “Demon with a Glass Hand” episode of Outer Limits (1964) and the revered “The City on the Edge of Forever” episode for Star Trek (1967). In addition, Harlan Ellison has edited some of the world’s most famous anthologies of science fiction short stories, like the game-changing collection Dangerous Visions (1967).

…But to conquer one god is to enter the service of another. A kind of celestial pact with an anti-devil that is prone to memory cramps; and Ellison’s universe unfolds, or unravels, like an endless chain of violence and suffering. it is however, man’s “raison détre” to fight: anger being the more human reaction to injustice and acceptance the less. On the one hand there is a pre-Christian view of man, an angry Biblical “humanism” which sanctions and condones individual violence in a violent universe. On the other, there are strong traces of the transcendentalist heritage. These invoke and guide man’s need at all moments and in all places to fuse with the universal essence…..

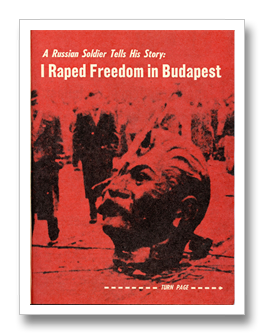

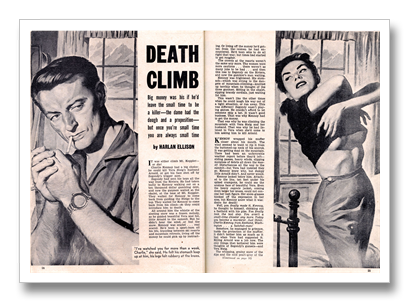

“But during his long career as a professional writer, which began in earnest in the mid-1950s, Harlan has actually written many different types of fiction and non-fiction. In the ‘50s and ‘60s, he wrote dozens of short stories for popular mystery, crime and detective magazines, such as The Saint and Crime and Justice Detective Story Magazine. He wrote even more fiction and non-fiction stories and articles for men’s bachelor magazines, like Playboy and Rogue. (He was also an Associate Editor of Rogue in the early 1960s.) Along the way, Harlan also had a few stories published in men’s adventure magazines. However, those have not been reprinted and were essentially “lost” — until recently. …Last last year, on this blog, I mentioned two Harlan Ellison stories I was surprised to find in men’s adventure magazines: “I Raped Freedom in Budapest,” a faux, as-told-to “true story” published in the August 1957 issue of Battle Cry and “Death Climb,” a noir thriller first published in the February 1957 issue True Men Stories.

…These would seem strange bedfellows, and the hero born of this mating is confronted with contradictory and often dark impulses: to oddly sort out the emotions of resisting the gods, yet seeking them everywhere. But no less a writer than Melville mined this perplexity in fashioning his mythic art out of such disparate elements. In a sense Ellison’s best work are the curious offspring of literature like Moby Dick; with the ambiguous and mysteriousness of Hawthorne in his last novel, “The Marble Faun” where a “hero” like Miriam is ambivalent about a destiny like the biblical Judith, one the one hand yearning for the white picket fence life while equally drawn to acts of savagery and murder.

ADDENDUM:

But for Harlan, paying the writer is a matter of longstanding principle. Actually, let me correct that by quoting what Harlan said in a press release when he sued Paramount in 2009 for continuing to make tons of money from the original Star Trek episodes without paying any additional fees to him and other writers who provided scripts for the series:

“F- – – -in’-A damn skippy! I’m no hypocrite. It ain’t about the ‘principle,’ friend, its about the MONEY!…Pay me and pay off all the other writers from whom you’ve made hundreds of thousands of millions of dollars…from OUR labors…just so you can float your fat asses in warm Bahamian waters. The Trek fans who know my City screenplay understand just exactly why I’m bare-fangs-of-Adamantium about this.”

Josh Wimmer interview:"I'm not afraid of death, and there is not one iota of suicide in me. All I want to make sure is that when the paper comes out, it says, 'Harlan Ellison died in his sleep.' You're talking to, essentially, a pretty happy guy. No, not 'pretty' happy -- that's television talk. I am inordinately happy. I am wonderfully happy. I am Icarus-flying-to-the-sun happy. I have led a magical life. I have led exactly the life I would wish to lead. I have led the life I guess that everybody in their heart of hearts wants to lead."

Josh Wimmer interview: Unlike many another writer who was educated and had college, I was on the road at age 13. Not because of anything bad with my family — it was just, I had a wanderlust. I was like the great writer Jim Tully or Jack London. I stood there at age 10 in Paynesville, Ohio, and I said, ‘This is all mine! All I gotta do is go and get it.’ And so I started running away. After a while, my mother said, ‘I’ll pack you sandwiches. Would you like peanut butter-and-jelly?’ Sometimes I’d get as far away as Kansas City and wind up working as carny and then wind up in jail, and get sent home. And I’d go back to school and I’d do very well, and then I’d run away again, and I’d run away to way up into Canada and work in a logging camp.”

——————————————————–

“When I was a little kid, and I was going to East High in Cleveland — my dad had died in ’49, and my mom and I were living there — I cut school one morning and I went to, I think it was Halle Brothers, down in the public terminal, the Cleveland Terminal Tower. And John Steinbeck was on tour, and he was speaking. And I was this little bitty kid clutching my schoolbooks, and I couldn’t get through the crowd — it was deep. John Steinbeck was standing on a little riser, and I crawled through people’s feet, and I got to, literally, the feet of John Steinbeck.

“And I listened to him, and then I turned and looked at the faces, and I said, ‘Oh. Boy. Now I know what famous is. Now I know what it is to be a mensch.’ Because there stood John Steinbeck, who was an ex-prizefighter — I mean, he looked like a fire plug! He was a tough guy. He worked like I had worked! I had ridden on boxcars, worked on demolition teams, and driving truck, and crops, and all that shit. But I was a little skinny squirt of a thing.

“And it was an epiphany. If I had stood under the Sistine Chapel ceiling, if I had finally reached Petra, a crimson city half as old as time, as they said of it, I would not have been more impressed. And that set the first part of my destiny. I was on the road, and I was doing my job, and my job was to tell stories.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS