Peter Pumpkinhead came to town

Spreading wisdom and cash around

Fed the starving and housed the poor

Showed the vatican what gold’s for

But he made too many enemies

Of the people who would keep us on our knees

Hooray for Peter Pumpkin

Who’ll pray for Peter Pumpkinhead? … ( Ballad of Peter Pumpkinhead, Andy Partridge)

The contempt and rage, much supported by the general public against Sir Robert Walpole was based on the belief that the ideals of liberty were being quickly eroded by self-seeking and corrupt politicians interested only in the riches power could bring. Henry Fielding articulated the dissatisfaction with incendiary plays performed in London:

Jonathan Jones:A great example of the seriousness of British "comic" art is William Hogarth's A Rake's Progress, prints of which are exhibited in Rude Britannia. It tells in pictures the salutary tale of a man driven to madness by spendthrift folly. The final scene takes place in the lunatic asylum Bethlehem Hospital. Was the rake in Bedlam ever meant to be hilarious? Obviously not. It is a macabre vision, one that even influenced Goya.

“As in the case of Pasquin the form of the drama is that of a rehearsal, a form which affords excellent opportunities for such explanatory asides as that addressed to the critic who complains of the attempt to review a year’s events in a single play: ”Sir,” says the author, ”if I comprise the whole actions of a year in half an hour, will you blame me, or those who have done so little in that time?” The long years of Walpole’s power were admittedly ”years without parallel in our history, for political stagnation.”

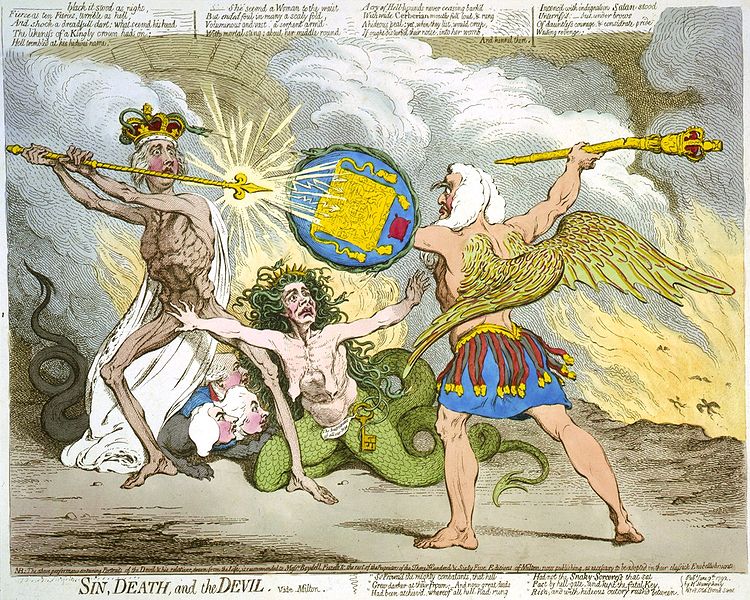

James Gillray. To Fielding’s enemies at the time, moreover, his new extremism had more to do with the profit motive than with political awakening, and as well as feeding the tastes of the season he may even have been courting hush money. Lockwood takes seriously Eliza Haywood’s suggestion that he wrote ‘in the hope of having some post given him by those whom he had abused, in order to silence his dramatic talent’, and suggests that after the passage of the Act ‘Fielding’s own wordless disappearance from the midst of the affair’ may reflect one among several other possible occasions on which he took money from Walpole to suppress existing writing or refrain from produ- cing more.30Whatever the case, Fielding’s career as a playwright was decisively halted, not so much by the requirement that new plays be submitted for censor- ship as by the stifling of competition entailed by the reinforcement of the old monopoly system."

Scene one discovers five ’blundering blockheads’ of politicians, in counsel with one silent ”little gentleman yonder in the chair;” who knows all and says nothing, and whose politics lie so deep that ”nothing but an inspir’d understanding can come at ’em.” The blockheads, however, have capacity enough to snatch hastily at the money lying on their council table. Walpole’s jealousy of power, it may be remembered, had driven almost every man of ability out of his ministry. Then comes a vivacious parody on the fashionable auctions of the day. Lots comprising ”a most curious remnant of Political Honesty,” a ”delicate piece of Patriotism,” and a ”very clear Conscience which has been worn by a judge and a bishop” and on which no dirt will stick, go for little or nothing, while Lot 8, ”a very considerable quantity of Interest at Court,” excites brisk bidding, and is finally knocked down for one thousand pounds. From the excellent fooling of the auction, the action suddenly changes to combined satire on the Ministry and on the two Cibbers, father and son. The Ministry are ingeniously implied to have been damn’d by the public; to give places with no attention to the capacity of the recipient; and to laugh at the dupes by whose money they live.

A like weakness for putting blockheads in office and for giving places to rogues, and a like contempt of the public, is allegorically conveyed in the third act, in which ’Apollo’ casts the parts for a performance among sundry unworthy actors, and declares that the people may grumble ’as much as they please, as long as we get their money.’ ”There sir,” cries the author to the critic of the rehearsal, ”is the sentiment of a great man.” The Great Man was a phrase, to use Pope’s words, ”by common use appropriated to the first minister”–that is, to Walpole…” ( Godden )

…Peter Pumpkinhead told the truth

But he made too many enemies…

Peter Pumpkinhead put to shame

Governments who would slur his name

Plots and sex scandals failed outright

Peter merely said

Any kind of love is alright

But he made too many enemies…

After Robert Walpole enacted an Act of Parliament in 1737 that effectively censored Henry Fielding’s satire off the stage, and his career into oblivion, the playwright turned away from literature and secured the professional qualifications needed to become a lawyer and hopefully support his wife and children. He touted the Western Circuit as a barrister, but briefs were few and meanly paid. He had no success. …

Godden:With leaders such as William Pitt and Lyttelton on the one hand, and the corrupt figure of Walpole on the other, there is no wonder that Fielding flung all his generous force into the effort to free England from so degrading a domination. Accordingly, in 1736, when the young Pitt’s impassioned eloquence was soon to alarm the Great Man –”we must muzzle that terrible Cornet of the Horse,” Sir Robert said–and when fierce and riotous hostility to the government had broken out in the country over an attempted Excise Bill, Fielding appears as a frankly political manager of the ”New Theatre” in the Haymarket.

His bitterness and resentment towards Walpole grew in intensity. He edited the major opposition newspaper, “The Champion” in order to eke out a threadbare existence, as well as an outlet to vent his rage. He was competent, but narrow political diatribe cramped the imagination. Walpole had succeeded in making Fielding a lost man, wandering in the fog. Fortunately, his fury at the lush sentimentality and hypocritical piety of Samuel Richardson’s “Pamela” became so intense that he had to express it in print. His ironic satire, “Shamela” , a book which he published under a pseudonym and never acknowledged, had great success. Almost immediately, he began a longer skit which grew into a full-sized book, and one that established Fielding as one of the founding fathers of the English novel.

…In the next scene the effrontery of the piece culminates in a ballet where the Prime Minister appears, leading a chorus of false patriots, who, to use Fielding’s own words, are set in the ’odious and contemptible light’ of a set of ”cunning self-interested fellows who for a little paltry bribe would give up the liberties and properties of their country.” These worthy patriots are of four types, the noisy, the cautious, the self-interested (he whose shop is his country) and the indolent (”who acts as I have seen a prudent man in company, fall asleep at the beginning of a fray and never wake ’till the end o’t”). To them enters Quidam, unblushingly announced in the play bill as ”Quidam, Anglice a Certain Person,” in other words Walpole himself. Quidam pours gold into the pockets of the four patriots, drinks with them, and then, when the ’bottle is out’ (a too frequent occurrence at Sir Robert’s table) takes up

his fiddle, strikes up a tune and dances off, the patriots dancing after him.

But even this is not all. ”Sir,” says the author, ”every one of these patriots have a hole in their pockets as Mr Quidam the fiddler there knows; so that he intends to make them dance ’till all the money is fall’n through, which he will pick up again and so not lose one halfpenny by his generosity….” We may suppose that the final scene lost nothing in breadth by the acting of Quidam; and it is not surprising that the immediate result was the subjugation not, alas! of the Ministry, but of the liberty of the stage. Walpole’s fall was delayed for three years; the destruction of the political stage was accomplished in three months.

Jonathan Jones:If Hogarth was a serious artist, so was James Gillray: his contortions of the human form (again, compare them with the grotesque images of his contemporary Goya) are unsettling, sick, twisted. British satirical art anticipated not so much modern comedy as modern art; it's one thing to set Gillray against Gerald Scarfe, but a really imaginative exhibition would show his distorted figures alongside Picasso's Three Dancers.

Joseph Andrews, a footman, was Pamela’s brother, and like Pamela his chastity, lovingly cherished, was endangered by his lascivious middle-aged employer, Lady Booby- a ludicrous situation that becomes serious and revealing through Fielding’s insight into the feelings of a rich, highly placed woman tormented by her lusts. Realizing his powers as he rapidly scribbled thousands of words, Fielding developed “Joseph Andrews” beyond satire into a comic epic, deliberately modeled on Cervante’s “Don Quixote”, and later enhanced and greatly refined by Jane Austen. His companion- the English Quixote- is Parson Adams, one of the great creations of English fiction, and one that other writers adopted as assiduously as other painters copied the pose of Titian’s “Venus of Urbino”.

Adams is the lovable, gullible, eccentric ass with a golden heart and unbreakable endurance. He is poor, bullied, set upon by Fate. Absent-minded, crazed with unrealizable hopes, and drugged with improbable ambitions, he is tossed from misfortune to misfortune, yet he is never soured, never rancorous, never evil-minded. He will fight but never bully; denounce but never rail; act but never deceive. The result is a character larger than life, yet as actual as a living man. Adams might easily have become incredible, but Fielding was careful to domesticate his epic by the use of realistic details. He drew on his carefully observed knowledge of the drifting riffraff of the eighteenth-century English highways to give verisimilitude to Adams’s adventures.

…Peter Pumpkinhead was too good

Had him nailed to a chunk of wood

He died grinning on live TV

Hanging there he looked a lot like you

And an awful lot like me!

But he made too many enemies…

Hooray for Peter Pumpkin

Who’ll pray for Peter Pumpkin

Hooray for Peter Pumpkinhead

Oh my oh my oh!

Doesn’t it make you want to cry oh? …

“the transplantation of Richardson’s character (‘with a lewd and ungenerous engraftment’, as Richardson complained in a letter to Lady Bradshaigh)into his own novel was a bold experiment for Fielding, in some ways bolder than the more purely parodic Shamela. Joseph Andrews tries something more difficult and complex: an overwriting, a kind of viral infection of the prior text which reads Pamela’s character in a more negative light but also tries to produce a valid fictional combination of new issues with classic form. Pamela’s opposite number is of course to begin with her supposed brother, Joseph, the chaste servant who emphatically does not seek cross-class marriage but pursues his original, given, pure affection for a dairymaid. Fanny, who turns out to be Pamela’s actual sibling, is also a carefully targeted example of real, unselfconscious, uncalculating female virtue.”

William Hogarth. Tate:The scene is set in Marylebone Old Church, north of Hyde Park, which was renowned for clandestine weddings. Having squandered his fortune, Tom attempts to appropriate another one, not through gainful employment, of course, but marriage. Having rejected marriage with the young, pretty and faithful Sarah, Tom’s bride is now an ageing, dumpy, one-eyed heiress. Sarah can be seen entering with Tom’s child in the background. Her attempt to interrupt this shameful ceremony is prevented by a brawl between her mother and an overzealous church attendant. Any hope of salvation for Tom now appears to have gone.

Bad barrister he may have been, but his imagination was alert. “Joseph Andrews” combined the realistic detail of a Defoe with some of the psychological subtlety of Richardson, and added a quality which neither possessed: a joy in human beings, and an irresistible sense of the delight of instinctive life; high spirits mixed with ironic compassion. The coldness of Defoe and the sensitive myopic probing of Richardson are replaced by an almost riotous appetite for life. Surprisingly, this boisterous book was written in a few weeks against a background of poverty and despair: Fielding’s daughter age six, was mortally ill, his wife on the verge of death , his pockets empty, his prospects miserable, and his own health insecure.

“Mrs Slipslop takes the role of Mrs Jewkes and turns it into a miniature comic epic of sexual and social frustration. Adams stands as a robust, if Quixotic, response to Richardson’s ineffectual Parson Williams, though the other clergy figures in the novel remind us of the range of theological positioning available. More or less every aspect of Richardson’s story finds some reversed mirror-image in Fielding’s. Richardson’s novel works by claustrophobic concentration on a single sexual-political encounter from which there is no escape: the problems caused by cross-class desire and ambition are resolved internally by internal reform, love, marriage, and consummation. Only at that point does the outside world return to deal with the now established couple/unit, who have to a large extent been sealed off.” ( Rawson )

Tate:Tom is now in The Fleet, the debtors’ prison. His previously plump wife, standing to his left, is now emaciated, indicating their desperate circumstances. In order to raise some cash, Tom has written a play, which lies rolled on the table next to him. Of course, this is as madcap a scheme as the alchemist seated at the back, attempting to make base metal into gold. This latest failure has infuriated his wife, who scolds him. Meanwhile, the jailer points at a ledger awaiting payment. With no course of action left to him, Tom has gone into a paralytic stupor.

London received his book with acclaim. A few critics , the poets Thomas Gray and William Shenstone were a little cool, but the public snapped up the first edition. Fielding next set upon his old rival, Sir Robert Walpole, who had toppled from power the same month that Fielding achieved his remarkable success as a novelist- February, 1742- a nice irony that was not lost on Fielding. He took a real character, Jonathan Wild, the notorious fence who had been exposed and hanged before one of London’s largest crowds in 1725, and he used Wild’s life as an allegory of Sir Robert Walpole’s ministry. The setting is Hogarthian in its realistic horror.

Fielding knew London’s debased inhabitants as well as the painter, whose close friend and admirer he was. The pimps, bawds, thieves, blackmailers, corrupt justices, and professional witnesses of London’s underworld are presented in “Jonathan Wild” with the savage realism of Defoe. And although Wild gets his desserts, this book’s most haunting quality is thesense of man’s brutality to man, the lurking disaster that awaits all good men: that no life,not even a life as virtuous as Heartfree’s- the foil to Wild- can escape pain, misery, degradation. However, even in circumstances as revolting as the tribulations of Heartfree, Fielding maintains that some men can remain good.

"When Wild was taken to the gallows at Tyburn on 24 May 1725, Daniel Defoe said that the crowd was far larger than any they had seen before and that, instead of any celebration or commiseration with the condemned, Wild's hanging was a great event, and tickets were sold in advance for the best vantage points (see the reproduction of the gallows ticket). Even in a year with a great many macabre spectacles, Wild drew an especially large and boisterous crowd. Eighteen-year-old Henry Fielding was in attendance. Wild was accompanied by William Sperry and the two Roberts Sanford and Harpham, three of the four prisoners who had been condemned to die with Wild a few days before. Because he was heavily drugged, he was the last to die after the three of them, without any difficulty that had happened at Sheppard's execution."

ADDENDUM:

“To some readers,Pamela’s fascination with sexual chastity has always seemed covertly pornographic, and in Joseph Andrews we have a much more open and straightforward eroticism, where eroticism has a purposeful place: Fanny is described lusciously for the reader early on and once again later, slightly undressed, for Joseph’s more particular benefit , so that there is no possible ambiguity about her sexual status. Moreover, we have a much broader dynamic of interaction and interference: Joseph is also depicted in sexually alluring terms by way of explanation for his perennial subjection to female desire, the great motor of the plot . Joseph is pursued sexually not only by Lady Booby, but also by Mrs Slipslop, whose sense of status and sexual lack renders her relationship with her mistress very unstable; and by casual Pamela-level women like Betty, the amiable servant who tends Joseph’s wounds.

Fanny herself is throughout the book the subject of repeated sexual harassment and predation, a fact which places her squarely under the correct protection of her male keepers, Adams and Joseph, since – in a violent world where men hold all the real power, physical and legal – Pamela-like reliance on virtue and chastity, however covertly effective for that heroine, is not likely to help much. The novel construes Fanny’s desire for Joseph as healthy and legitimate in comparison with Pamela’s autoerotic sham-modesty. After a series of increasingly warm physical encounters, Joseph and Fanny retire to enjoy a sexual union which is quite explicitly superior to considerations of rank: their ‘Rewards’ are ‘so great and sweet, that I apprehendJoseph neither envied the noblest Duke, nor Fanny the finest Duchess that night. (Rawson )

Tate:Tom is seen losing another fortune in a dingy gaming den. A number of fortunes are changing hands, underlined by the reactions of the men around the card-table in the centre. Meanwhile a nightwatchman on the right sounds the alarm as smoke pours through the ceiling. Tom kneels on the floor, distraught. Like the majority of the people in the room, he is too obsessed with gambling to notice or care that the building is on fire. He looks angrily towards heaven with his arms extended and his fists clenched, railing against God or fate.

Jonathan Wild: The public’s mood had shifted; they supported the average man and resented authority figures. Wild’s trial occurred at the same time as that of the Lord Chancellor, Lord Thomas Parker, 1st Earl of Macclesfield, for taking £100,000 in bribes. With the changing tide, it appeared at last to Wild’s gang that their leader would not escape, and they began to come forward. Slowly, gang members began to turn evidence on him, until all of his activities, including his grand scheme of running and then hanging thieves, became known. Additionally, evidence was offered as to Wild’s frequent bribery of public officers.

Wild’s final trial occurred at the Old Bailey on 15 May. He was tried on two indictments of privately stealing of lace from Catherine Statham (a lace-seller who had visited him in prison on 10 March) at Holborn on 22 January. He was acquitted of the first charge, but with Statham’s evidence presented against him on the second charge, he was convicted and sentenced to death. Terrified, Wild asked for a reprieve but was refused. He could not eat or go to church, and suffered from insanity and gout. On the morning of his execution, in fear of death, he attempted suicide by drinking a large dose of laudanum, but because he was weakened by fasting, he vomited violently and sank into a coma that he would not awaken from. …

COMMENTS

COMMENTS