“A carved altar is displayed for its acrobat iconography; omitted is recognition of its function as a slaying stone. On altars like this, a sacrificial victim was laid on his back, arms and legs held down, while an executioner knifed out the living heart, Aztec style. The corpse was rolled down the temple steps and flayed, its bloody skin worn in dance by a priest. …Maya connoisseurship extended to the arts of immolation and — what to call it? — the etiquette of a naked lunch. The qualities of a good king consisted not in character but in the ability to manipulate the supernatural world through ritual activity: voluntary bloodletting through the tongue, ears and penis or liturgic slaughter of victims requisitioned from among slaves and peasants. …” ( Mullarkey )

---Eric S. Thompson, the distinguished Mayaist, wrote: “Maya prayer is directed to material ends. I cannot imagine a Maya praying for ability to resist temptation, to love his neighbors better.… There is no concept of goodness in his religion, which demanded a bloody, not a contrite, heart.”---

The most perplexing problem concerning the Maya is how to explain the sudden breakdown of their society and the subsequent gradual abandonment of the whole lowland area with its hundreds of important sites, at the base of the Yucatan peninsula. In about 900 A.D. the elaborate Maya calendar ceases. There are no large building projects after that date. The illiterate populace was evidently without the leadership of their priests, for they set up pieces of broken monuments with carved inscriptions in meaningless ways.

”It is well known that ancient Mayan culture was uncompromisingly brutal. The Maya were subject to a mythology that strong-armed human will to the dictates of an unforgiving array of supernatural forces. The gods offered not redemption, but retribution for failing to meet their demands. The Mayan people, particularly those who had no claim to political or religious power, knew well enough not to mess with the order of things. Even then there were no guarantees.

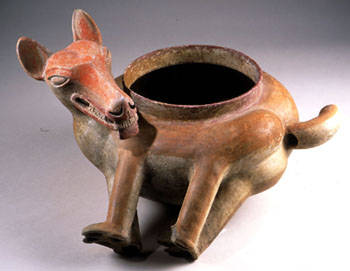

The ancient Maya created a sophisticated society predicated upon slavery, mutilation, human sacrifice and probably cannibalism. Without these daily terrors—or, as the Met diplomatically puts it, “ritual performances”—the arrival of a new morn was in doubt. An incalculable loss of human life led to impressive achievements in art, architecture, mathematics and urban planning. Should our knowledge of a culture’s practices color- or diminish—an appreciation for its art?” ( Mario Naves )

Many explanations have been advanced, but the most likely one may be that the people revolted and overthrew their priesthood. During the late Classic years the tempo of building and of erecting Stelae was greatly accelerated. These projects, with all their attendant artistic embellishment, may be evidence of pressure on the people and on the priests. Once involved on a course of worship and propitiation involving great monuments and the work of numerous craftsmen and artists, no leader could afford to relax. Furthermore, the priesthood could not afford mistakes. They were bound to have explanations and excuses ready in case their predictions, based on their almanacs, proved false. They could either blames the Gods, themselves or the people, and it is not likely that the latter were often spared.

”The Maya are not alone among peoples who ruled with a blatant disregard for human life. No culture is blameless when it comes to acts of atrocity. The 20th century witnessed barbarity on an unprecedented scale perpetrated by cultures of no mean accomplishment. But would the Met or any of our other great institutions dare to mount an exhibition titled Treasures of the Third Reich? … Yet the question remains: By aestheticizing what is essentially religious propaganda intended to foster a culture of fear, do we encourage ethical ambivalence?”

Stan Parchin:Aside from the statue's curled mustache, this Maya masterpiece is also unusual in terms of its prayerful pose and intense gaze. Its stance suggests a state of trance attained by an ajaw or a diviner. It has also been conjectured that the figure once held a square mirror. The Maya believed that mirrors were tools of divination that created portals to the otherworld. If indeed this sculpture supported one, such a conclusion would lend credence to the statue's interpretation as a representation of a Maya with special religious knowledge or supernatural abilities.

It is not difficult to imagine that in a situation of this kind enough mistakes could lead a people under tension to revolt. Most archeologists now believe that the final collapse of the most highly organized and artistically and intellectually developed stage of Maya civilization was brought about by such a revolt against their leaders. Other explanations have been suggested chiefly having to do with the difficulties of a large population practicing agriculture in the tropical forest.

The two explanations may well be connected, for if a cycle of drought, upsetting the delicate balance of success and failure of the crops, had coincided with priestly predictions of good times and continued demand for labor, the people might have overcome their awe and destroyed the hierarchy in a day. No matter how one may regard these attempts at explanation, the fact remains that Maya civilization collapsed at just the point when tension may be inferred to have been at a high level. With the loss of control by the priestly class, the great ceremonial centers fell into disrepair, art was no longer created, and the population both dispersed and decreased. The Classic period was at an end.

Tikal is just one of among manyMayan ruins to have been excavated. Others include the walled city of Mayapan, one of the warring cities of the post classic period, Dzibilchaltun, an enormous site in the Yucatan. Another is Tiahuanaco in highland Bolivia; an important center long before the Incas came, and its artistic influence is evident throughout the Central Andes. The most important developments in South America have been in Ecuador, due in part to the early contact between Ecuador and Japan and a later visit from Asia about 200 B.C. Models of houses with saddle roofs and columns were completely unknown in the New World at that time, and ther

little doubt that the arrival of a vessel from Asia is responsible for their existence.Less than seventy-five years ago the earliest known cultures of Peru were the Classic ones, and the Formative period of Mexico was thought to date back only to about 300 A.D. Now the history of humanity in this hemisphere has become much clearer, but many chapters remain a blank. Even the well known periods are not complete.

”However distant, foreign or severe Mayan art may be to contemporary eyes, its aesthetic dimension can’t be discounted. The order, meticulousness and all-consuming intensity of each of the myriad objects displayed in “Treasures of Sacred Maya Kings” is indisputable—whether it be a plate, a piece of jewelry, a stele or the lid of a pot featuring the God Itzamna perched on the back of a peccary….The astonishing beauty created by the Maya is inseparable from the cruelty espoused by their culture. If we reject the art on moral grounds, we doubt its ability to transcend the constraints of time and circumstance. If we accept it without philosophical qualm, we risk ignoring our common humanity.

…The Met’s presentation makes a polite hash of history for purposes that are grounded less in art than in political expediency. The contemporary mindset can’t admit that, ultimately, aesthetics aren’t a source for moral values. Squeezing art into a conceptualist straitjacket is a denial of its inherent complexity. Banishing Mayan art to its “culture and time” is a cheat: It robs us of the full aesthetic experience, however disquieting it may be. Art provides many things; easy answers aren’t among them.” ( Naves )

"Royal Maya tombs were “lavishly furnished with grave goods,” we learn. No one mentions that those goods included the kings’s slaves, killed for the occasion. Chat labels identify the rain gods by their symbolic insignia but not by their demand for oblations. Since rain gods were fond of small things, these were frequently children, hurled into deep wells still living or with their hearts torn out. (Children, prized for their virginity, gratified other Maya gods as well.)"

ADDENDUM:

Maureen Mullarkey: They were also prisoners of their own mythology. Among the Maya, every fault lay in the stars. All genius ministered to the star-bending, god-cajoling powers of divinely ordained elites. Knowledge for its own sake was unthinkable, absent from tribal psychology. The Maya created fine roads but had no wheeled vehicles, no dray animals, no plow. Prosperity was sustained by peonage and slave labor. Everything — from limestone blocks to timbers and produce — was carried on human backs. Warfare supplied captives for the indigenous slave trade.

Jonathan Jones:Critics of Mel Gibson's film Apocalypto affect to be shocked by images of decapitation, throat-cutting and still-beating hearts ripped from sacrificial victims. They should take a glance at the art of the Maya. In the Mexico gallery in London's British Museum are reliefs carved by Maya artists in the eighth century AD, whose revelation of a culture drenched in blood will make your eyes pop out. The reliefs portray Lord Bird Jaguar and his wife the Lady B'alam Mut, performing a bloodletting ritual on themselves. She passes a rope studded with thorns through her tongue; he uses a stingray's stinger to draw blood from his penis. If this is what powerful Maya did to their own bodies to celebrate the birth of an heir, imagine what happened to prisoners.

Divinities were numerous and hungry for human sacrifice. Propitiating a galaxy of gods was the job of an extensive priestly caste, a dynastic aristocracy and its reinforcing bureaucracy. Literacy, a symbol of sacred knowledge and divine sanction, was jealously guarded. Land belonged to the gods; only priests and princes could access the secrets of distribution, among other matters of ancestral wisdom.

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS