The most important effect of his great work was its direct contradiction to the dogma of the Catholic church to that time. He was condemned by the church and his books burned. After all, he had come out and said that the earth was much older than the church’s 2,000 year-old claim that it had been created circa 4,000 BC. The basis for this, of course, was purely scientific. Buffon’s most controversial claim, and his most accurate one, was that the similarities between apes and humans were so great as to rule out mere coincidence, and he went so far as to predict that they shared a common ancestor. …Buffon was absolutely brilliant with words, earning him the nickname, “the great phrasemonger.”…Speaking of his many detractors, he said, “I shall keep absolute silence . . . and let their attacks fall upon themselves.”

---The Embarkation for Cythera 1717; Oil on canvas, 129 x 194 cm; Musée du Louvre, Paris Genre painting came back into favour when the Academy admitted Watteau to its ranks in 1717 on the presentation of this work, the subject of which was so novel that the term "fête galante" was coined to describe it. Drawing its inspiration from the theatre, the picture shows lovers in party dress--some wearing the pilgrim's hooded cape--coming to seek love on the island of Cythera, under the statue of its goddess, Venus. In an iridescent landscape which owes much to Venetian painting, allegory is caught up in the swirl of couples in a reverie; a new and less didactic interpretation of Titian's elegiac mode. ---

In 1753, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, was elected a member of the French Academy and on the day of his official appointment he had to deliver his inaugural address. Towards the end of his speech to the noble assembly occurs the dictum that has become the most often quoted epigram on the subject of style:”Le style est l’homme meme”; style is the man himself.

Of the two terms in Buffon’s equation, we are inclined to understand “style” to be the independent variable, bexause we presuppose “man” can only be the independent one. It is man, we think, who has to play the sovereign role in the relationship of style and man. Style is, then, nothing but a form which is adopted by man in order to express himself. Style, we think, is the way in which a man speaks or paints, the way in which he moves, dresses or makes love, the way in which he treats other people and behaves in society. Style-as is understood- is, thus, a genuine manifestation of man, and, compared to Buffon, a substantial difference concerning the relationship of style to man.

John Werestka:Confusion about the ‘subject’ of Watteau’s paintings continues today and, standing in front of them, it is easy to understand why.9 Showing ‘the meeting of men and women, clothed in choice fabrics, and who hold court in a landscape or architectural setting of glorious unreality, dancing with each other, making music or chatting’, these pictures do not seem to be ‘about’ anything. 10 Critical reception of Watteau’s work has therefore been torn between a condemnation of it as sublime vacuity, recording the polite but ultimately empty banter of a class doomed to fall to the scythe of the Revolution, or as a sometimes misanthropic critique of love and (un)faithfulness, courting and barely concealed eroticism in the dying glow of the grand siècle. ...

In the 18th century, however, it was exactly the other way round. The dependent variable was not style, but man, Man did not yet manifest himself in style. Instead, man himself was nothing but a manifestation of style. Style was not created by man; man was created by style. Thus when Buffon pronounced his famous dictum, he employed a conception of style that was very unlike the one we have.

In Buffon’s usage, “man” is a much more restrictive term than its meaning today. Rather than a simple human being in a pure sense, it rather meant something like “gentleman”. Being acknowledged as “un homme” was an achievement and one had to take pains to earn that title. Among other things, one had to conform to a set of rules that determined the way of presenting oneself; in social life just as well as in art and literature. It is clear then that style, in this understanding, indeed does not emerge from man. Its exactly the other way round: man emerges from style. A man qualifies as such only if he is obedient to the imperatives of style. In the 18th century it is a set of abstract rules that constitutes style- and, in turn, man.

Leigh Foster:The masked face stared back at the audience, rebuffing spectators' search for familiar forms, transforming the known into the exotic. The absence of such highly specific information as the face would convey imparted a greater articulateness to the gestures of the limbs, the swaying of the torso, and the tiniest inclinations of the head. While the body's movement acquired greater expressivity through the neutrality of the face, the exact nature of the characters' thoughts or feelings remained ambiguous. As a result the character, like Watteau's figures, became a wistful apparition signaling poignantly toward the expressivity of feeling as well as toward feeling itself....

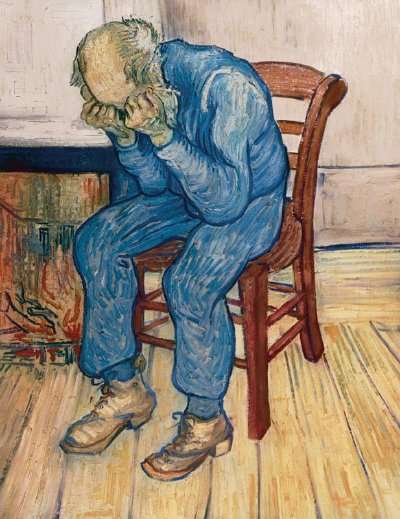

In order to illustrate this pre-modern constellation in which man has to play the role of a subordinate variable in relation to style it is advisable to take a short look at the work of Buffon’s near contemporary Antoine Watteau. During his lifetime Watteau earned his repute mostly for his elaboration of a genre called the “fete galante”. The gazes and gestures of the melancholic noblemen that he depicted always reflect and reveal the rhetorical requirements of their highly styled social interaction. Concerning the way in which Watteau painted his pictures, Watteau also reflects the rhetorical requirements of his genre.

When we look at the figures in one of Watteau’s typical paintings, we will feel that their gazes, their postures, their whole repertoire of social interaction appears to be extremely ornamental and artificial; a number of highly stereotypical gestures of seduction and affectation as we can see them in lots of other paintings as well. But this, of course, has indeed been the grammar of behavior in the times of Watteau. People performed an endless sequence of prefigured and repetitive ceremonious activities. Their day consisted of “periodical sighing and kneeling down”.

content/uploads/2010/11/watteau6.jpg" alt="" width="500" height="386" />

"... the artist who Bryson is talking about that is Jean-Antoine Watteau an eighteenth century French artist Bryson says in Watteau a whole narrative structure insists on meaning but at the same time withholds or avoids meaning..."

COMMENTS

COMMENTS