This is the era of the Napoleonic Wars, of the Battle of Waterloo and the Battle of Trafalgar, and the Duke of Wellington and Admiral Nelson. The waltz was a scandalous new dance craze, and stylish women cropped their hair and wore clinging gowns with daring cleavage. Men gambled incessantly, winning and losing vast fortunes and family estates on a single hand of cards. Dueling, though outlawed, was still practiced. Beethoven was writing his symphonies, Byron was a celebrated poet, and dandies such as Beau Brummell dictated fashion….

---It was an age of contrasts, and of political and economic turmoil. England was at war with France during most of this period. "Society" consisted of a few thousand privileged people, the upper classes and the nobility, also referred as the ton or the beau monde. While these wealthy few hunted on their estates and danced at glittering balls and routs, the rest of England was in the grip of change brought about by the industrial revolution. Desperate working class "Luddites" rioted and smashed the machines that threatened their jobs.---

What is sure is that, in 1788, right at the time when the administration seemed to be stabler, with William Pitt the Younger as Prime Minister and the increased popularity of the king among his subjects, George III began to suffer from a mental illness that made him, for example, speak for hours with no interruption. Several doctors, including Francis Willis, tried to find a treatment, while rumours about the king’s derangement spread. Consequently, the Parliament began to debate provisions for regency. Even though the sovereign recovered, his disease reappeared soon afterwards, until, in 1811, he became so dangerously ill that he had to accept the Regency Act, with which full powers were given to his son, the Prince of Wales, despite his hatred towards him. But before that Prince George, was burning holes in his pocket with whatever cash and credit he could lay his hands on….

It was a lesson in basic monetary and fiscal policy.Quantitative easing at the micro level. The solution to the financial difficulties of Prince George was to marry a German princess, breed an heir, and allow a grateful country to discharge his debts and increase his income. The alternative was a personal crisis of monumental proportions which would almost certainly entail a sharp contraction in his style of living. He was far too middle-aged to face that. So he married.

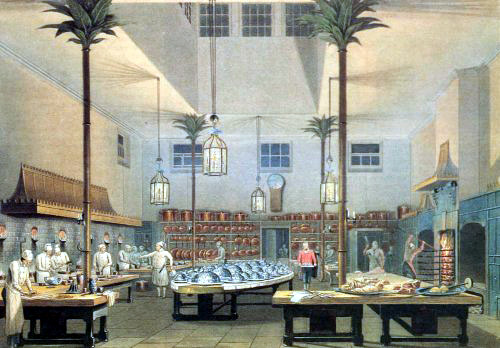

---The Brighton Pavillion is his masterpiece. It showed his genius and his ability to marry more than one school of architecture. Dorothea de Lieven described the Pavilion succintly in a letter to her lover Prince Metternich: "How can one describe such a piece of architecture (as) the King's palace here? The style is a mixture of Moorish, Tartar, Gothic and Chinese, and all in stone and iron. It is a whim which has already cost 700,000 pounds; and it is still not fit to live in."---

He loathed his strange bride and got through the marriage ceremony only by fortifying himself with brandy. His wife was dotty: a hoyendish, blowsy, free-speaking German wench who dressed in outrageous taste, swore like a hostler, and smelt like a farmyard. Or so the Prince and his friends said- at least it gave an excuse for the vile way he treated her. He manged, however, to get his Princess pregnant, and duty done and the daughter born, he turned the Princess out of his house but not out of his life. She careened around Europe in vulgar ostentation, as much to embarrass the Prince as to enjoy herself. Certainly the Prince’s legal marriage was the most disastrous act of his life.

Once he had extricated himself from this horror, he naturally wished to re-create the years with Mrs. Fitzherbert, which now glowed in his imagination. Her pride bruised, she showed her former indifference, which once again fanned the Prince’s ardor to fever heat. There was nothing like denial to raise the Prince’s passion. After a becoming interval, Mrs. Fitzherbert sent a priest off to Rome for advice. It was apt: return to your husband. She did, and both returned to Brighton.

King George III. Ruler of the British Empire from 1760 to 1820, he presided over a considerable time span marked by great

achievements and questionable decisions alike. Britain’s navy had proven itself as the undisputed world leader, defeating Napoleonic

France and strengthening King George’s influence across the world. On the other hand, mismanagement of the American colonies led to the Boston Tea Party, and ultimately, the Declaration of Independence. The establishment of Australia as a penal colony, also controversial, was also conducted during his reign. These events left somewhat of a shadow over the legacy of King George III, “The King Who Lost America”. Subtle and not-so-subtle indications of Parliament’s hesitancy with King George’s rule stemmed from his periodic bouts of madness – bouts that while well documented would not receive a diagnosis for nearly 200 years. In the meantime Price George played house on a grand scale….

Not only did Mrs. Fitzherbert make the Prince supremely happy- the next eight years, she was to say, were the happiest in his life- she also made him creative. Again he began to play about with the Pavilion. In 1802, the gift of some Chinese wallpaper, received no doubt because he had created a Chinese room at Carlton House in 1801, gave him the idea of making not only a Chinese gallery at the Pavilion but a room with walls of painted glass which gave one the impression of being inside a Chinese lantern.

For the next few years, shortage of money and the need to complete the stables- no horses, nor grooms for that matter, had ever been more splendidly housed- limited the Prince’s ambitions, but the Pavilion was enlarged a little and the interior decoration made more and more what the English thought to be Chinese. But the Prince was not satisfied, and he decided to reconstruct the Pavilion, to turn it from a princely cottage into a miniature palace, small in size, yet rich, fabulous, Oriental in decoration.

le="brighton19" src="/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/brighton19.jpg" alt="" width="300" height="229" />

"The Prince Regent was known for his excesses and expensive tastes, and his architect John Nash succeeded in fulfilling the Prince’s most outrageous wishes. The Gothic Revival was in full swing during the Regency Era, including the love for all things mid-Eastern, Chinoise, and Arabian. "

Not a Chinese pagoda: the Prince was moving away from Chinese towards what he conceived to be an Indian style. Already at Sezincote in Gloucestrshire, a nabob, returned with a huge fortune from India, had built himself an Oriental palace; fortunately for him, his brother, S.P. Cockerell-was an excellent architect who took his task very seriously and carefully used water-color drawings of actual Indian buildings. Te result was strange, but pleasing. William Porden, who built the stables at Brighton, had worked with Cockerell, and he used the exceptionally original style of decoration at Brighton.

This entranced the Prince; in 1805, he commissioned Humphrey Repton to plan an Aladdin-like transformation of his classical marine villa into an Indian palace. The Prince praised the drawings but did not build. Once more he was broke. And possibly he had doubts about Repton’s scheme, which conformed very strictly to Indian models. Highly disciplined and rather dry in tone, it lacked, perhaps, the personal accent for which the Prince’s imagination was searching.

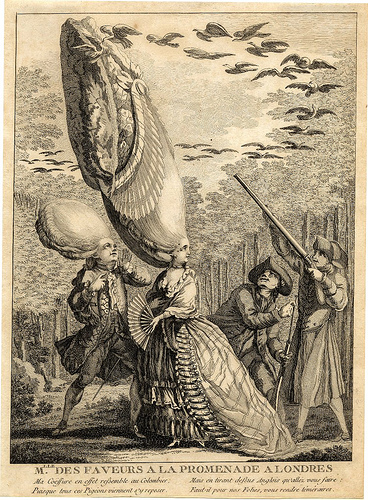

"Beau Brummel may have set the standard for elegance and style but not every man aspiring to Brummel's flair succeeded. The style soon went over the top. What flowed naturally and unselfconsciously from Beau Brummel all too often became affectation and pretension in others and it was this class of dandies that became the subject of caricature and ridicule. "

He hesitated for another six years until indeed, the final madness of his father made him King in all but name. The he got hold of a regal income and began to build as no English king had ever built before. The encouragement he gave to John Nash, the Surveyor-General whom he personally appointed in 1815, made the Regent as responsible as anyone for the most beautiful domestic architecture London possesses- the great terraces of Regent’s Park. Nash’s pavilion at Brighton however, owed as much to the effects of time and experience on the Prince’s character as to Nash’s architectural genius. It was the final expression of his life. Every detail in decoration, furnishing and color was personally supervised by the Regent and, if need be, changed time and time again until he judged it to be right. To understand the strange fantasy that came to life by Brighton’s seashore , it is necessary to understand how time had changed the Prince….

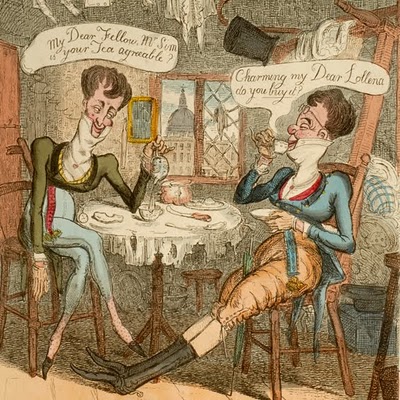

"This was the first of Gillray’s many references to the supposed miserliness and avarice of King George III and Queen Charlotte, and the profligacy of the Prince of Wales. While Gillray’s ambitions to become a “serious” artist were never realized, his parodies of the language of “fine art” and the dramatic formulae of history painters, as in this “mock-heroic” print, gave his satire bite. In a setting that evokes Renaissance grandeur (with quotes from Raphael), Gillray’s King and Queen pocket, with nary a glance, sacks of money proffered by the Prime Minister, William Pitt (who keeps some coins for himself). The Prince (in the right background), his clothes in tatters (the King declined to pay his son’s debts), reluctantly accepts a note for £200,000 from the Duc d’Orléans. In the foreground, a destitute, crippled sailor begs in vain for succor. By dedicating this print to Jacques Necker, Louis XVI’s finance minister, Gillray contrasted France’s fiscal policies with those of England, which was faced with increasing national debt."

By 1815, his youth had passed; Mrs. Fitzherbert had been rejected a second time, indded another reason for his delay in reconstructing the Pavilion was the change in direction of his amorous life, which kept him away from Brighton for a year or two. Gross in body, somewhat wandering in mind, prone to invalidism, the Prince was driven farther into his private dream world by the antics of his wife and the hatred of his subjects. ….

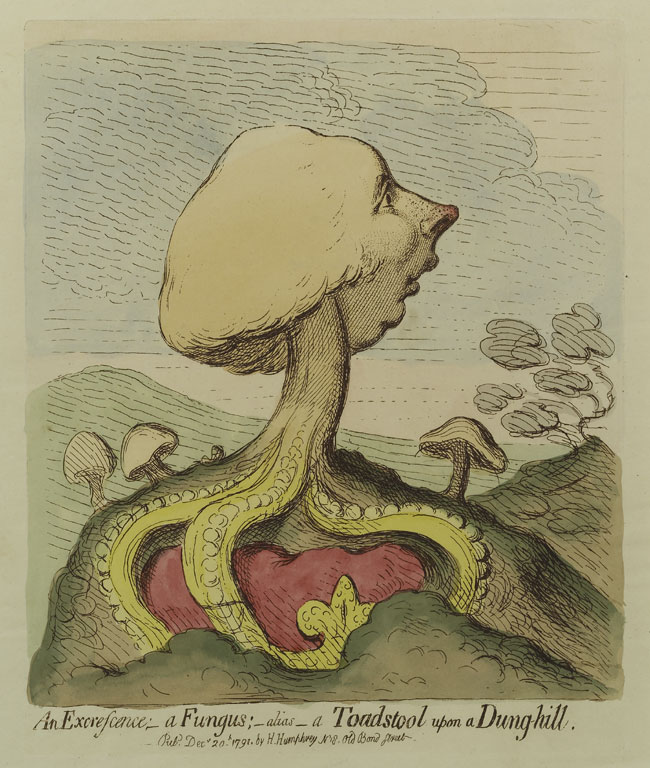

"In this scurrilous and extraordinarily imaginative caricature, Gillray transforms the head of William Pitt into a mushroom, whose saprophytic roots take the shape of the royal crown. Pitt was First Lord of the Treasury and Prime Minister at the age of 24. In this satire, Gillray suggests that the ambitious young Pitt was dependent upon royal favor, while he increasingly arrogated the King’s power for himself, particularly during the Regency crisis, when George III was first afflicted with mental illness (November 1788–May 1789). Gillray injected another wry note when he equated the source of Pitt’s power, the King, with a dunghill. Pitt’s nose is colored a delicate pink, alluding to his fondness for claret and port."

ADDENDUM:

Prince George had been 21 when, in 1783, he had made his first visit to Brighton, which, although still a village (“Brighthelmstone”), had delighted him with assemblies, balls, gambling, and promenading by the sands of the English Channel. Here was the ideal place to escape the stodgy royal father who so disliked him, and to be with people of wit, beauty, and style. After this marriage, in 1786 he leased “the superior farmhouse” in the valley of the Steine River which he commissioned architect Henry Holland to refurbish as a neoclassical mansion, but which he was subsequently to transform into a Coleridgian Xanadu with exotic Chinese interiors and Moghul exteriors. Since he was underage and since the Catholic ceremony was not recognized under English law, Prinny was free to marry again — to Princess Caroline of Brunswick in 1795. He agreed to marry the hideously heavy German princess on condition that Parliament pay his debts of £650,000. Mind you, now 33, George was no midget at 17 stone (238 lbs.) He sought divorce from her, but the scandal that notion engendered ended with her death in 1821. When George IV visited Scotland in 1822, Sir Walter Scott orchestrated a magnificent reception for him, despite his Hanoverian lineage andÊlingering Jacobite memories of his uncle, Butcher Cumberland, and the ignominious defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie in Culloden in 1745.

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS