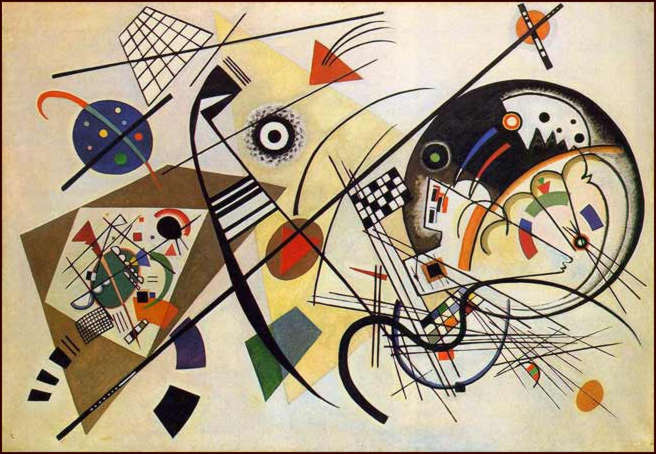

“A member asked what was the ethos of German Expressionism, suggesting it was ‘cultural despair’. The speaker reiterated his title phrase: ‘an explosive cocktail of cultural despair and political instability’, adding that the German character seemed almost morbid in its realistic attitude to the tragedy and horrors of war, in deep contrast to the romantic evasive approach of some of the English WWI artists… Quoting from Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art, ‘When Religion, Science and Morality are shaken,by the mighty hand of Nietzsche, When the external support threatens to collapse then mans gaze turns away from the external towards himself.’

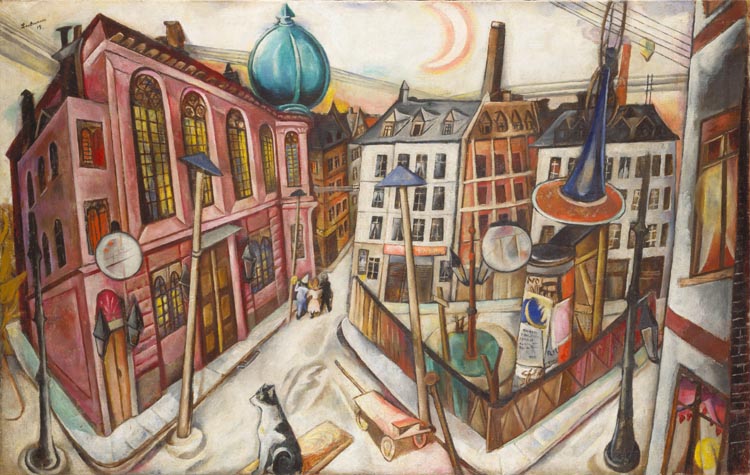

Expressionist art offers examples of the uncanny "second sight": Beckmann pictures the Frankfurt synagogue in 1919 with its wall slanting as if they might topple at any moment.

The nervous, alienated and often brilliant culture of the Weimar republic can appear uncomfortably like America’s own. But is the sickness that killed the German Republic the same sickness that afflicts America now?

Although many express an admiration for Noam Chomsky that is unbounded, as well as his interlocutor Chris Hedges, the interview Hedges conducted with Chomsky on Truthdig making parallels between contemporary America and Weimar Germany was perceived by many as nonsensical. Here are the most relevant paragraphs:

“It is very similar to late Weimar Germany,” Chomsky told me when I called him at his office in Cambridge, Mass. “The parallels are striking. There was also tremendous disillusionment with the parliamentary system. The most striking fact about Weimar was not that the Nazis managed to destroy the Social Democrats and the Communists but that the traditional parties, the Conservative and Liberal parties, were hated and disappeared. It left a vacuum which the Nazis very cleverly and intelligently managed to take over.”…

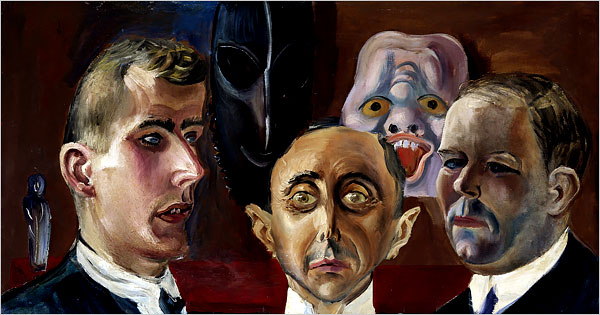

Otto Dix.---A brief article from the June 19, 1932 New York Times should give you a feel for the desperate situation in Germany: In the Bischofshem forest hikers found the corpses of a family of five—father, mother, and three children from 3 to 7—a brief note in the man’s pocket stating that economic misery had determined him and his wife to commit suicide, and take their children with them. “The courageous don’t grow old,” the note concluded. Its writer was 35 years old, a World War veteran, out of work, trying to eke out a living selling newspapers. He had shot his wife and children, and then himself. Eighteen thousand people killed themselves in Germany last year, according to the provisional figures. Berlin alone had nearly seven hundred suicides the first four months of this year. The suicide curve seems to be rising steeply, and common sense interprets this as the reflection of constantly increasing economic pressure.---

The art that had been dominant changed with and through the times. By late 1923 the inflationary period, with its fantastic peaks and ruinous effects, was at an end. Political unrest let up for a time. True, one Adolf Hitler tried an unsuccessful “putsch” in Munisch in November, only to be arrested and imprisoned. But assassination, that favorite form of political expressionism, appeared to be on the wane. Between 1924 and 1929 the republic seemed to be on safer ground. Even political isolation receded before the conciliatory foreign policy of Gustav Stresemann, and in 1926 Germany was at last permitted to join the League of Nations. The enemies of the republic were relatively quiescent, its friends more optimistic.

They had reason to be; these were the brief years when Germany basked in the comfortable legend of the “Golden Twenties”, while the forces of destruction- the Dr. Caligari’s- were as busy as before, though less noisy. Hitler was soon out of jail, and his party was active again. Yet there was a good deal of evidence to which a professional optimist might appeal.

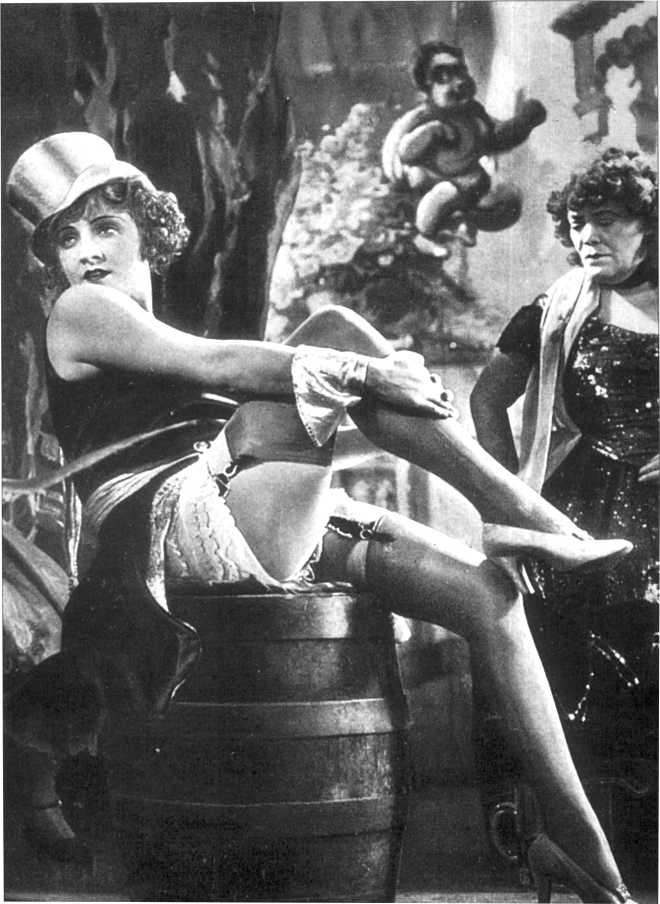

As the decadent, compulsive temptress Lola in the 1930 film "The Blue Angel", Marlene Dietrich symbolized rightist elements in Weimar Germany.

…“The United States is extremely lucky that no honest, charismatic figure has arisen,” Chomsky went on. “Every charismatic figure is such an obvious crook that he destroys himself, like McCarthy or Nixon or the evangelist preachers. If somebody comes along who is charismatic and honest this country is in real trouble because of the frustration, disillusionment, the justified anger and the absence of any coherent response. What are people supposed to think if someone says ‘I have got an answer, we have an enemy’? There it was the Jews. Here it will be the illegal immigrants and the blacks. We will be told that white males are a persecuted minority. We will be told we have to defend ourselves and the honor of the nation. Military force will be exalted. People will be beaten up. This could become an overwhelming force. And if it happens it will be more dangerous than Germany. The United States is the world power. Germany was powerful but had more powerful antagonists. I don’t think all this is very far away. If the polls are accurate it is not the Republicans but the right-wing Republicans, the crazed Republicans, who will sweep the next election.”

Otto Dix. Sunday Stroll. "The other thing missing entirely from Chomsky’s assessment is the differences between the German working class in the Weimar Republic and our own situation. To put it bluntly, there is no fascist threat in the U.S. today because there is no Communist threat. The two movements are dialectically related. Despite all the hysteria about “socialism” on Fox News and at Tea Party rallies, there is not the slightest sign that American workers are thinking in class terms, let alone radicalizing. In fact the overall response of workers to economic crisis now is pretty much the same as it h

een since every downturn since the early 1970s, namely to seek personal solutions."The most impressive piece of evidence, certainly the most visible, was that enormously influential school of design, the Bauhaus. Founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus had an early, struggling existence, defining its program and defying its detractors,in Weimar. Then in 1925 right-wing politicians, aided by reactionary architects- men who proved by their very actions that the gold of the Golden twenties was tarnished- drove the bauhaus out of the city for which the republic was named. It moved to Dessau,and there it flowered for a few precarious years. Its philosophy, articulated by Gropius and his associates in broadsides, pamphlets, and exhibitions, was the merging of aesthetics and craftsmanship in the service of “total architecture.”

The famous school buildings in Dessau, which brilliantly exemplified this philosophy, were designed by Gropius himself. And he was seconded by a staff as brilliant as he was: Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Josef Albers, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy.

Louisproyect.wordpress.com:I am afraid that Noam Chomsky and Chris Hedges are succumbing to the kind of fascists under the bed hysteria that I have seen on the left going back to the Nixon administration, a politician widely accused at the time of being a new Adolph Hitler. One can only wish that the current occupant of the White House was only half as progressive as Nixon whose Keynesian economics and pro-environment policies put Obama to shame. Perhaps the only analogy with the Weimar Republic that makes sense is the “lesser evil” politics that sections of the left promoted then and now. The Socialist Party in Germany kept backing bourgeois politicians as an alternative to Hitler, even as their anti-working class policies were creating the resentment among backward layers that helped feed the Nazi movement.

This group, dedicated teachers and all,ventured into the farthest reaches of abstract art and practical design. They designed chairs and lamps and rugs that remain striking today, with their handsome simplicity, their freedom from cliches, and their sheer utility. The bauhaus, which included some of the most memorable artists of the twentieth century, tried to marry function and beauty, ideology and practicality, the machine and freedom. This last- the marriage between machine and freedom- was perhaps the most daring and important of all.

Gropius and his associates accepted modernity; they wanted to master the industrial age, not to flee it. As long as the Golden twenties were, or seemed, golden, the Bauhaus succeeded; when depression and the rise of right-wing extremism threatened the fragile republic, the Bauhaus faded. In 1932 it left its buildings in Dessau and moved to Berlin, where it vegetated for a final year or so in shabby quarters.

The history of the Bauhaus- its stormy beginnings, splendid but short maturity, and pathetic and forlorn end- mirrors the course of Weimar culture as a whole. And there were other, subtler bits of testimony from the arts that all was not well. In 1930, the year that later historians were inclined to think of as the last year of truly republican existence, the playwright Carl Zuckermayer adapted for the movies a widely read novel by Heinrich Mann, first published in 1904. The film, “The Blue Angel” , would make Marlene Dietrich, her voice, and her legs, world famous.

James Turk:The Federal Reserve is following the footsteps of the central bank in Weimar Germany. It is the same path taken by many central banks that have issued countless fiat currencies based on nothing but government promises. It is the path to the fiat currency graveyard, and the once almighty US dollar - which long ago used to be "as good as gold", just like the Reichsmark once held that same exalted title - is knocking at the graveyard's gate. This insight about the importance of gold and shortcomings of fiat currency is not suprising, nor is it new. Here is what Rep. Howard Buffett, father of Wall Street legend Warren Buffett, had to say on May 4, 1948. "Our finances will never be brought into order until Congress is compelled to do so. Making our money redeemable in gold will create this compulsion."

It was the story of a straight-laced high school teacher, filled with resentful rage against his jaunty, often well-to-do students, who takes up with a cabaret entertainer. In the novel, mordant and hilarious, the improbable pair drives many respectable townspeople to ruin by running a gambling hall; the two are arrested in the end, but even in the police van they seem to have triumphed over bourgeois respectability. But the film de-emphasized satire and instead became lachrymose; in a new ending the high school teacher, acted to the hilt by Emil Jannings, goes mad with jealousy, lumbers back to the classroom- scene of his most humiliating defeats- puts his head on the desk, and dies.

Heinrich Mann was a highly political writer whom some radical journalists considered a good prospect for the presidency of the republic. Strangely enough, he made no objection to Zuckermayer’s changes in his satirical creation. Yet, however blandly Mann accepted these changes, the shift from satire to pathos was significant, and in its own way, ominous.

Wassily Kandinsky. Traverse Line 1923.Kandinsky's abstractions brought to painting the severe, geometric functionalism of Bauhaus design.

ADDENDUM:

…”By comparison, Germany had been the scene of massive and organized resistance ever since the end of WWI. Massive Socialist and Communist Parties were involved in one revolutionary struggle after another starting with Rosa Luxemburg’s ill-fated Spartacist uprising. In 1921 and 1923, there were Communist-led insurrectionary struggles that were doomed to fail because of ultraleft sectarian mistakes largely inspired by Bela Kun, the Comintern emissary to Germany. For example, in Saxony coal miners often used dynamite against the army and cops just as Bolivian tin miners did in their revolution in 1952. By comparison, the Massey Energy company has the blood of 29 dead miners on its hands and the trade unions in West Virginia do nothing but issue press releases. This is not to speak of the utter lack of a radical movement embedded within the coal mines. If anything the radical movement had more of a presence in the 1970s but as is the case across the board it declined into nothingness. If fascism is meant to stave off working class revolution, then it would serve no purpose at all in the U.S. today.

Blackburn: Valentine now emphasised that one of the ways of making sense of the numerous painters an different styles of the so-called German Expressionism was to see the post-war art as ‘The New Objectivity’ or ‘Der Neue Sachlichkieit ‘, when the reality and horrors of war force the object back onto the consciousness of the artist. As the three examples of this he took, Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Kathe Kollwitz (for social commentary), showing the appalling state of Germany after the war and the German Communist Revolution of Jan 1919. These included Grosz’s ‘Metropolis’ Dix’s war etchings and maimed veterans, and Kathe Kollwitz Memorial woodcut to the murdered Karl Liebknecht ‘ The Living to the Dead’.

Since Chomsky’s parameters include Blacks and “illegal immigrants” (his words, unfortunately—nobody is illegal) rather than workers, it is worth taking a look at how much of a threat they pose to the existing system as well. To start with, the sad truth is that the Black community has not been mobilized for nearly a quarter-century and if anything is even more demobilized today under Obama. Illusions in a “Black president” have been widespread on the left except among the vanguard like Glen Ford’s Black Agenda website. 25 years ago there were still stirrings of Black Power that occasionally led to conferences for a Black political party, demands for reparation, as well as other signs that the sixties were still alive. Today there is virtually nothing like this going on.

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS