Accusations of elitism, populous slanders of the word as pejorative have been unleashed as aprt of the American cultural landscape in this season of discontent. Can we take lessons form the Weimar Republic? The right wing tone of academia in Weimar Germany was a case study in a fiercely self-conscious elite. In their university fraternities, many of them notorious dueling brotherhoods, they developed or kept alive , a corporate sense of their own superiority over mere outsiders, over Jews, over miserable merchants, who had never fought a duel.

… Both Walter Benjamin and Georges Bataille were hostile to the general Hegelian logic of sublimation and sublation that sought to transfigure horror into something culturally elevating. Both were suspicious of calls for a return to a lost Gemeinschaft through symbolic restoration in architectural terms. It was a rejection of what could be termed “digestive” remembering; something that can only be premised on a certain forgetting, the forgetting of everything that resists incorporation into its system, such as the suicides of Benjamin’s anti-war protestor friends, which are then abjected as so much unnecessary waste.

To bear a dueling scar on one’s face was a mark of honor, a badge of bravery, an opening to future preferment. There were exceptions to be sure, but were not frequent enough, or powerful enough, to moderate the right wing tone of students everywhere in Germany. These young brutes were rebels only in the sense that they were ready to rebel , and then only against the republic. They were not very rebellious in other respects. In their right wing extremism, they were obedient followers of their professors.

Oskar Kokoschka, Die Windsbraut (The Bride of the Wind), 1914. This painting shows Kokoschka and Alma Mahler as a shipwrecked pair in stormy seas. "He satisfied my life and he destroyed it", she said.

…”Language,” Benjamin wrote, “shows clearly that memory is not the instrument of exploring the past but its theater. It is the medium of past experience, as the ground is the medium in which dead cities lie interred. He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging. This confers the tone and bearing of genuine reminiscences. He must not be afraid to return again and again to the same matter; to scatter it as one scatters earth, to turn it over as one turns over soil.”

It was a warning against the premature, affirmatively cultural smoothing over of real contradictions. Unlike the commemorative lyrics filled with the traditional healing rhetoric that has allowed a Jay Winter to claim that “a complex process of re-sacralization marks the poetry of the war,” Benjamin’s sonnets to his war dead–or rather anti-war dead–enacted a ritual of unreconciled duality. Here eternal salvation and no less eternal sorrow remained in uneasy juxtaposition, as antinomies that resist dialectical sublation. As Bernhild Boie has noted, whereas the nationalist mobilization of religious rhetoric, in the work of, say, Friedrich Gundolf, sacrificed individual souls for the collective good, Benjamin’s poems refused to do so: “Because Gundolf pompously sacralized the profane horror of the hour, he robbed conscience of its responsibility. Benjamin had conceptualized his sonnet cycle as the radical antithesis of such violence.” ( Jay Martin )…

The German professoriate had developed into a closed, highly conservative , extraordinarily patriotic caste during Bismark’s days and retained its convictions- a mixture of unpolitical servility and reactionary chauvinism- through the end of the empire and the Weimar Republic; It was a kantian idealism, derived from that philosophy the categorical imperative of a German victory, a German monarchy and a return to the familiar. The lack of opportunities to democrats, socialists and Jews remained a priority as a badge of reactionary honor, similar to the proud wearing of a dueling scar. In Weimar, as before, professors and students supported, inflamed and richly deserved one another.

…Only by a ritualized repetition–the value of ritual, according to Adorno, having been taught Benjamin by the poetry of Stefan George–could the violence of amnesia be forestalled. Only by refusing false symbolic closure in the present might there still be a chance in the future for the true paradise sought by the idealist self-destroyers buried in their separate and separated graves; the trope of troubled burial. It has long been recognized that the war had a decisive effect on all of Benjamin’s later work. As one commentator typically put it, “it is the first world war which provides the traumatic background to Benjamin’s culture theory,fascism its ultimate context.” In particular, it has been acknowledged as a powerful stimulus to his remarkable thoughts on the themes of experience and remembrance, which were to be so crucial a part of his idiosyncratic legacy….

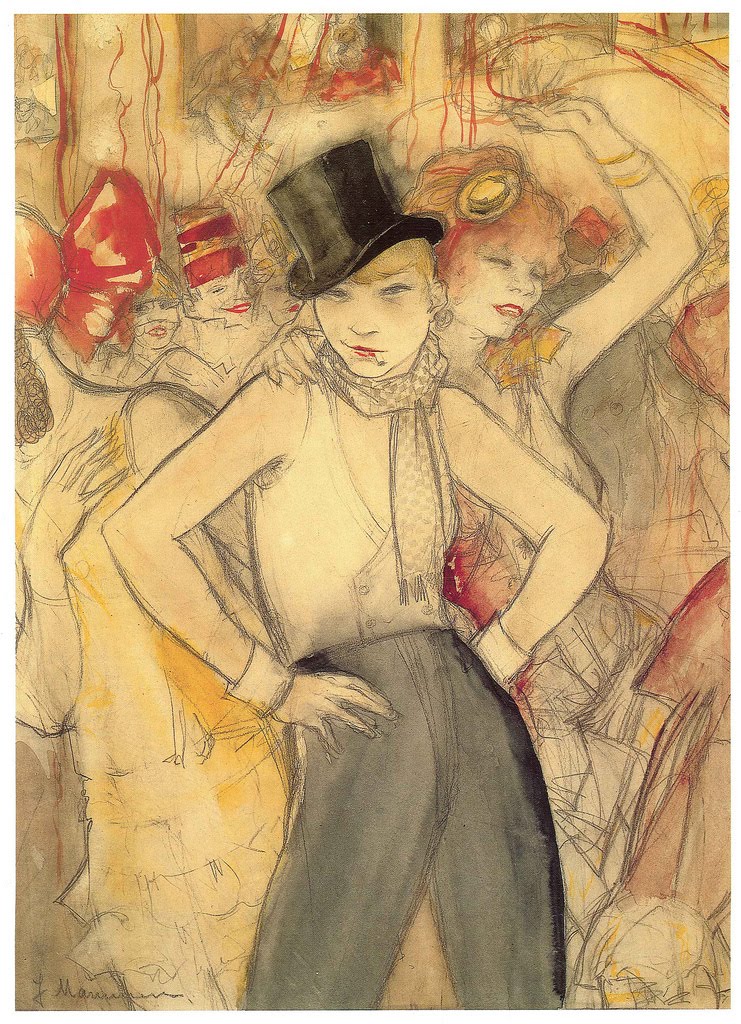

Student extremism took many forms. Most students agreed only on what they detested, and they swallowed the novels of Ernst Junger who celebrated war as a glorious experience, or the plays of those among the expressionists who preached violence , any kind of violence as an essential explosion of ones feelings. These feelings were rarely ones of rage against militarism or exploitation and rarely direct bids fro power. They were masks for social and economic conservatism or pathetic anti-intellectualism – a wooly mindedness fed on intoxicating poetry , the aristocratic te

ngs of a half comprehended Nietzsche, and an ineradicable sense of Germanic superiority.…One of the most frequently cited passages in Benjamin’s work, from his 1936 essay “The Storyteller,” is often cited to show its relevance. It reads: With the First World War a process began to become apparent which has not halted since then. Was it not noticeable at the end of the war that men returned from the battlefield grown silent–not richer, but poorer in communicable experience? What ten years later was poured out in the flood of war books was anything but experience that goes from mouth to mouth. And there was nothing remarkable about that. For never has experience been contradicted more thoroughly than strategic experience by tactical warfare, economic experience by inflation, bodily experience by mechanical warfare, moral experience by those in power. A generation that had gone to school on a horse-drawn streetcar now stood under the open sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath those clouds, in a field of force of destructive torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body.” …

Hence the riots against jewish professors, the cheering of Nazi doctrinaires- of racists, preaching the biological supremacy of the blond Aryan, who came to infest the universities in increasing numbers after 1930. In the long run, and in view of their fate, these youths arouse pity: they went to their deaths with incomprehensible verses or swinish slogans on their lips, corrupted by those who should have enlightened them.

…In August, 1914, Walter Benjamin, along with many other twenty-two year olds was drafted, but refused because of badly swollen hands, after which he faked palsy and was able to postpone induction until another order arrived to report in January,191. Again he was able to avoid conscription by trickery, undergoing hypnosis to simulate the symptoms of sciatica. Shortly thereafter, Benjamin left Germany for Bern, Switzerland with the hypnotist, who was also his new wife, Dora Kellner. This was Benjamin’s first

emigration from his native country in a period of crisis, but not his last. After the armistice, the Benjamins returned to Berlin in

March, 1919, where he spent the turbulent years of the Weimar Republic until forced to flee to Paris in 1933….

The hypnosis is interesting, because in Germany, it was the Dr. Caligari’s and Thomas Mann’s Cipolla’s who held judgeships and university chairs. These were the hypnotists who painted glorious portraits of past greatness and drew caricatures of domestic “traitors” -Jews and Communists- who had lost the war behind the back of the brave German army; who told seductive tales of magnificent comradeship in war, when men were men and killing was exhilarating.

Walter Benjamin was thus spared the glory and misery of the Fronterlebnis, the community of the trenches that so powerfully marked his generation for the rest of their lives, if they were lucky enough, that is, to survive it. But he did not,in fact, escape the violence caused by the war. Indeed, it might be said to have sought him out immediately after the hostilities were declared. On August 8, l914, two of his friends, the nineteen-year-old poet Friedrich (Fritz) Heinle, to whom he was passionately devoted, and Heinle’s lover, Frederika (Rika) Seligson, the sister of one of Benjamin’s closest comrades in the Youth Movement, Carla Seligson,

committed suicide together in Berlin. Their act, carried out by turning on the gas, was designed as a dramatic protest against the war, a war in which lethal gas was, as we know, to take many more victims….

In the midst of these visions that these German hypnotists conjured up for their fascinated and willing audiences, the real sources of misery were neglected and deliberately obscured: the war had been prolonged and then lost by bemedaled butchers whom the public was now invited to worship and obey. The public was discredited by the respectable bankers and judges who talked of honor and objectivity when they meant partiality and treason.

…Benjamin learned of the news when he was awakened by an express letter from Heinle with the grim message “You will find us lying in the Meeting House.” The place of their deaths was not chosen accidentally; “the Meeting House” (Sprechsaal) was the apartment Benjamin had rented as a “debating chamber” for his faction of the Movement According to Pierre Missac, who cameto know Benjamin in l1937, he was able to overcome his shame at surviving only by “mythologizing the lost friendship.” Heinle, he implied in a 1917 essay on Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, was like Prince Myshkin, who had lived “an immortal life…that without monument, without memory, perhaps without witness, must remain unforgettable.” In the quarter century that followed the initial trauma, ended only by his own suicide in 1940, Benjamin composed seventy-three unpublished sonnets, discovered in the Bibliothèque nationale in 1981. Some fifty-two of these he arranged in a cycle dedicated to Heinle.

Although several commentators have shown that Benjamin’s disillusionment with the Youth Movement began well before the war, the suicides intensified and brought to a climax his disgust for the devil’s pact he saw between the Movement’s alleged idealism, its celebration of pure Geist, and its patriotic defense of the state. With the death of the adolescent Heinle came the end of Benjamin’s faith in the redemptive mission of youth itself, although he remained stubbornly wedded to its ideals. During the rest of the war, Benjamin distanced himself from others who defended it, such as Martin Buber, and brutally dropped old friends from the Youth Movement, such as Herbert Belmore.Instead, he gravitated towards like-minded critics of the conflict, although never himself actively engaging in anti-war agitation, and wrote increasingly apocalyptic treatises on the crisis of Western culture.

A duel scarred rightist student. ---Korps student from Nuremberg, Cologne, 1928 Copyright August Sander Archive---

His estrangement from the German university community, which reached its climax with the now notorious rejection of his Habilitationsschrift at the University of Frankfurt in 1925, began with his disgust at the spectacle of so many distinguished professors enthusiastically supporting the so-called “ideas of 1914.” The empty bombast of their chauvinist rhetoric hastened his abandonment of traditional notions of linguistic communication, as well as whatever faith he may have had left in the German Jewish fetish of Kultur and Bildung.

Despite the efforts by celebrants of the Fronterlebnis such as Ernst Jünger to recapture its alleged communal solidarity, Benjamin knew that the technologically manufactured slaughter of the Western front was anything but an “inner experience” worth reenacting in peacetime. In his trenchant l930 review of the collection edited by Jünger entitled War and Warrior, he ferociously denounced the aestheticization of violence and glorification of the “fascist class warrior” he saw lurking behind this new cult of “eternal” war. There could be nothing “beautiful” about such carnage.

Steadfastly anti-Hegelian, he protested against a notion of memory as a “re-membering” of what had been dismembered, as an anamnestic totalization of the detotalized. Scornfully rejecting the ways in which culture–at least in its “affirmative” mode–can function to cushion the blows of trauma, he wanted to compel his readers to face squarely what had happened and confront its

deepest sources rather than let the wounds scar over. Rather than rebuilding the psychological “protective shield” (Reizschutz) that Freud saw as penetrated by trauma, he labored to keep it lowered so that the pain would not be numbed. For the ultimate source of the pain was not merely the war itself. As Kevin Newmark has noted:

“This generalization was evident, inter alia, in his influential discussion of Baudelaire’s response to the shocks of modern life. Although he clearly admired the poet’s ability to transform his dueling with those shocks into aesthetic creativity and saw him as a pioneer of post-auratic art, he also understood that at times, to cite Michael Levine, “the very defense that was supposed to intercept the shocks of urban life itself turns out to be something that must be defended against.” Baudelaire’s lyric parrying of distressful stimuli, Benjamin implied, could serve to prevent them from becoming truly traumatic, keeping them, that is, at the level of unreflected episodes with no long-term effect on the mind, which failed to register them beyond the moment of impact. Although he understood the reasons for doing so, and indeed has often been read as simply endorsing the poet’s heroic stance, Benjamin also tacitly warned against the risks of such defensiveness, which was of a piece with other techniques of anaesthesia developed in the nineteenth century to dull the pain of modern life.

Shockparrying purchases its fragile peace, he suggested, at the cost of a deeper understanding of the sources of the shocks, which might ultimately lead to changing them. Shocks, in short, must be allowed to develop into full-fledged traumas, for reasons that will be clarified later. In so arguing, Benjamin was profoundly at odds not only with the 19thcentury culture of anaesthesia, but also with the postwar, international “culture of commemoration” that, as George Mosse, Annette Becker and Jay Winter have recently shown, desperately drew on all the resources of tradition and the sacred it could muster to provide meaning and consolation for the survivors. Rejecting, for example, the cult of nature that led to the construction of Heldenhaine (heroes

groves) of oaks and boulders in the German forests, Benjamin wrote:

It should be said as bitterly as possible: in the face of this ‘landscape of total mobilization’ the German feeling for nature has had an undreamed-of upsurge….Etching the landscape with flaming banners and trenches, technology wanted to recreate the heroic features of German Idealism. It went astray. What is considered heroic were the features of Hippocrates, the features of death. Deeply

imbued with its own depravity, technology gave shape to the apocalyptic face of nature and reduced nature to silence–even though this technology had the power to give nature its voice.

No pseudo-romantic simulation of pastoral tranquility in cemeteries that were disguised as bucolic landscapes could undo the damage. No ceremonies of reintegration into a community that was already deeply divided before the war could suture the wounds.

Benjamin’s saturnine attraction to Trauerspiel, the endless, repetitive “play” of mourning -or more precisely, melancholy-, as opposed to Trauerarbeit, the allegedly “healthy” “working through” of grief, was, however, more than a response to the war experience in general It appeared to be specifically linked to his reluctance to close the books on his friends’ anti-war suicides. As he argued in the case of another suicide, that of the innocent Ottilie in Goethe’s Elective Affinities, the work to which Benjamin devoted a remarkable study in 1922,31 making sense of such acts in terms of sacrifice, atonement and reconciliation could only reinforce the evil power of mythic fatalism,and the myth-like social compulsions of bourgeois society.

Benjamin’s insistence on not letting the dead rest in peace, at least as long as they remained in false graves, was at the heart of his celebrated critique of historicist attitudes towards the past. Whereas most historicists tacitly assumed a smooth continuity between past and present, based on an Olympian distance from an allegedly objective story, he assumed the guise of the “destructive character” who wanted to blast open the seemingly progressive continuum of history, reconstellating the debris in patterns that would somehow provide flashes of insight into the redemptive potential hidden behind the official narrative. It is hard not to hear echoes of his personal anguish over the suicides of his friends in this.

…The Weimar Republic was always fragile, but it was not doomed from the start- that was another part of Germany’s hypnotist’s tale. We too are haunted; Weimar Germany, and present day America- both haunted republics. Hopefully, the ghosts are not the same.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Dave – your writing ( I assume it is your’s ) on Weimar era Germany is fantastic – so fantastic in fact, that I really want to

( sorry…hit enter a bit too soon )…..

( I really want to )….quote it in a scholarly context…..

Could you email me enough info on the author so that it can be quoted in length with proper acknowledgement in the footnotes?

thanks

Joel, let me get back to you on Monday. It was written a while back, so I need a refresher myself. Glad you enjoyed!