In the realm of art, Joan Miro’s earliest and most lasting impression was provided by the frescoes of medieval Catalonia. Of course, Hell and the Apocalypse were the favorite themes of these artists. We meet men sizzling in the cauldron, and a host of other ingenious tortures. An executioner jigsaws his victim from head to toe, and both seem equally delighted by the pretty zig-zag pattern traced by the blade. The air is thick with flying devils and angels, roving stars and fishtail doves. …

Miro, The Poetess. 1940. A gay design in which the viewer can identify a few of the swirling objects as birds and eyes, but may have difficulty identifying a poetess

This violent, indigenous fancy found an eminently suitable outlet in the direct, expressive idiom provided by the Romanesque style. The Gothic, on the other hand, stifled it with its carefully weighted , meticulous intellectuality , as did the succession of styles evolved out of the Renaissance. This points to the central predicament of Catalan art: native qualities constantly run the risk of entering into conflict with the foreign styles taken over as a result of Catalonia’s no less native internationalism and curiosity. For Catalan art to flourish, foreign style and hereditary traits must coincide. This had happened in the case of the Romanesque , but Catalonia’s vigorous extravagance had not found another real outlet until the birth of a style at the turn of the nineteenth-century variously known as Art Nouveau or Jugendstil. When this did occur , it resulted at once in the emergence of a creator greatly admired by Miro: the architect Gaudi.

"One of the best and astonishing images of the Dance of Death is in . It is a fresco made by Vincent of Kastav around 1474. It is a very strange yet wonderful image full of all classes of men, women, children, and between them skeletons walk in procession. There are ten characters in this dance; each one is accompanied by Death. In-between the skeletons dance the pope, the cardinal, the bishop, the king, the queen, the innkeeper, the child, the maimed, the knight, and finally the merchant, who stands by a table covered with goods. The skeletons are naked and some of them play music; bagpipes, mandolins and wind instruments. The merchant, who is last in joining the dance, tries to bribe Death by pointing at his money. His efforts are futile; Death will never spare a "dancer" in exchange for mere riches."http://fantasytop.com/art.html?start=44

Salvador Dali, another Catalonian, once said of his countrymen: “All Catalonians are paranoiacs.” Gaudi, in the course of his fairly long life, completed only a dozen major projects, but they amply testify to the violence and inventiveness of his eccentricity. The columns of his houses erupt like eucalyptus trees; their facades are corroded by a rash of bright ceramic splinters assembled into mosaics; their balconies are overgrown with iron vines; and the chimneys on their roofs are like monstrous bubbles that never manage to burst. Gaudi gave free rein to his imagination. Irregularity was the law. Pyramids are poised on their tips, colonnades lean enough to make the Tower of Pisa seem straight as an arrow in comparison. Everywhere, profusion and planned anarchy prevail.

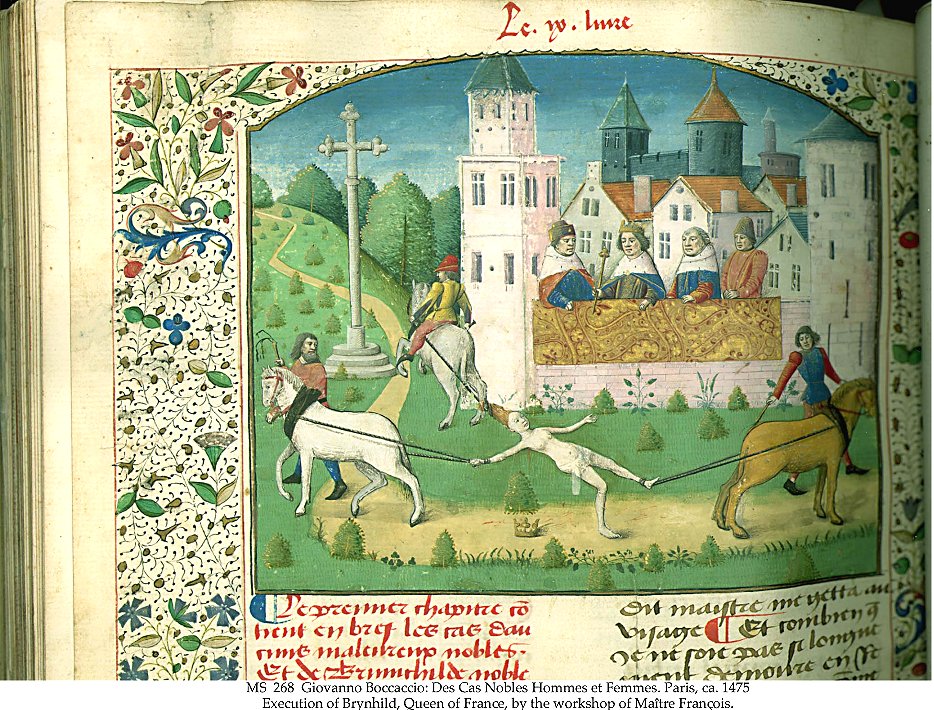

"1475 The execution of Brunehaut was illustrated in Laurent de Premier translated edition of Giovanno Boccaccio’s Des Cas Nobles Hommes et Femmes."

To materialize his fancies,Gaudi resorted to bold, often prophetic means. As Miro and the surrealists were to do a generation or two later, Gaudi used odds and ends in his creations: shells from the nearby beach, scraps from the textile mill for which he was building a church. Gaudi affirmed that the source of his aberrant inventions was not gratuitous fantasy but nature. His claim is justified, for the landscape of Catalonia can vie in extravagance with the richest imagination; it can be said to belong to the same eccentric lineage as Gaudi and Miro.

These are the real roots that fed Miro’s magic flowers. But roots are invisible; from 1923 onward, Miro appeared to be a true member and product of the School of Paris. Underneath his work as well as his life unfolded in a simple line. It was sometimes deflected but never broken by external influences. Miro was like a Captain Nemo who had died deep into his own element; the disturbances on the surface affected him only distantly.

Marina Carlson:“Colorful” and “vibrant” are two words that I have always thought described Spain accurately, and Gaudi embodies this spirit: he was designing in the late 1800′s, not too long after Napoleon’s makeover of Paris that gave it structure and uniformity, and yet made things that are worlds away from what other architects were making at the time. I have to imagine that Gaudi and Haussmann probably hated each other: Gaudi the creative boundaries-pusher not afraid to take risks in design, and Haussmann the cold, structure fanatic that kept everything organized and familiar. I would have sided with Gaudi.http://marinacarlson.wordpress.com/2010/12/02/barefoot-in-barcelona/

For a while Miro practiced pure automatism as advocated by the surrealists. Soon, however, a horde of neatly described if unidentifiable monsters invaded his stage. In the early thirties, geometrical abstraction reached its high water mark, and Miro was influenced by the painters Mondrian, Leger and Arp; his forms became less anecdotal, his compositions more severe. Even so, he remained himself.

In 1936, the specter of civil war rose over Spain. Again Miro was affected: his fantastic scenes became anguished, oppressive; the dreams turned into nightmare. When the Second World War broke out, Miro then left a collapsed France . Miro sought shelter amidst the stars- or rather behind them. In the cacophony of a de

ed world, his “Constellations” captured an echo of the music of the spheres.

Constellation. Wakening at Dawn. 1941. Carroll Dunham:Beginning around 1924 Miro gradually cut himself free from most of the things that had previously given painting its "look." From our present cultural perspective we have trouble really feeling the radicality and depth of some early Modernism, which can look fussy and illustrational to us. But it's important to see how radical this work was--nothing like it had appeared before. Miro's break and subsequent blossoming obviously didn't occur in a vacuum, but they have a special quality. He was close in spirit to the prehistoric artists of Altamira and Lascaux; the impulses in the work seem "human" rather than "Modern" or "European." There is a wonderful comfort with playfulness and sexuality in the work. He achieved a scale and an openness several generations ahead of the conventional wisdom in painting, and he integrated language into his imagery through the collapse of writing and drawing into one activity. The implications of all this are still being explored.

In 1940, Miro moved back to Spain, with an occasional visit to Paris. When the war ended and Miro’s art reappeared on the international art scene, it was evident that something in it had changed again. The elements that peopled Miro’s painting had turned from things into signs. They no longer composed a world, but a language. Progress, for signs, lies in clarity and elegance of formulation. At first sharp and minute, Miro’s writing became looser, more dashing; it now had the sovereign nonchalance, the decorative appeal of Oriental calligraphy. Still, the substance of which the signs are made cannot change greatly; but the substance on which they are written can.

Read More:

http://musingsofanartstudent.blogspot.com/2010_10_01_archive.html

http://fantasytop.com/art.html?start=44

http://oceanflynn.wordpress.com/category/academic-disciplines/humanities/

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_n5_v32/ai_15143622/pg_7/?tag=content;col1

ADDENDUM:

Carroll Dunham:

His evolution after World War II is a puzzle. In an exhibition of this size one feels confronted simultaneously by the best and the worst that Modern art has to offer–sometimes it isn’t even clear which is which. On the one hand he seems to have settled into the middle of a Miro industry, and much of the work has an empty, formulaic quality. But he also glimpsed something brighter, less delicate, and less polite than anything he had done earlier. I think we can still learn a lot from paintings of the early ’50s like The Bird Boom-Boom Makes His Appeal to the Head Onion Peel, 1952. Later, the big “Blue” paintings from 1961 and the “Mural Paintings” from 1962 show him talking back to the younger American painters for whom he had been crucially influential twenty years before. This level of engagement seems exemplary and not at all typical of his peers.

Painting. 1950. "The person who is eager to please becomes an overachiever. He is not an ambitious person, for he has no relationship to a larger context, to the world of ideas. He has nothing to do with the Olympus complex; he has no notion of "pie in the sky"; the people he wants to please are those he knows and loves. His intensity is ferocious but localized, and therefore safe. Miro was successful. He found a formula and went on doing it for fifty years. After all, he had to sell. It was the dealers who turned him into a sculptor, which he was not--Miro's sculptures are not thought through. In going from two to three dimensions, a cutout taken from a painting is not enough. There is more to sculpture than a blob of clay with a fork in it. Miro was too successful for his own good. In making sculpture he went out of his league. In her catalogue essay for the MoMA show, Carolyn Lanchner, the show's curator, belabors the idea that Miro was cold-blooded and calculating, as his abstract pictures show. Nobody disagrees. But when Miro was doing the portraits, landscapes, and still fifes in his early realistic manner, he was deeply involved and original. Only when he turned to abstraction did his paintings become predictable and repetitive. His later use of French vocabulary was acquired; it's touching but not convincing. I like the work before it becomes abstract and French-speaking. It's like Robert Motherwell using "Je t'aime" when he barely spoke French."...

The sculpture became both more and less interesting after the war. He found a way to be more direct, leaving behind his rather generic surrealist juxtapositions of the ’30s. Miro clearly had a gift for working with clay; there’s something good in the sculpture when it functions as an objectified analogue for the presences in his paintings. A lot of this work, however, raises disturbing questions about how many kinds of things an artist really needs to do.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS