…Even the Church was in trouble: it was rumored that not one soul had entered paradise since the Great Schism began. Outbreaks of the plague were common, taxes were high, and political stability unknown. In such a world, a beautiful Book of Hours provided welcome escape, at least for the few who could afford one.

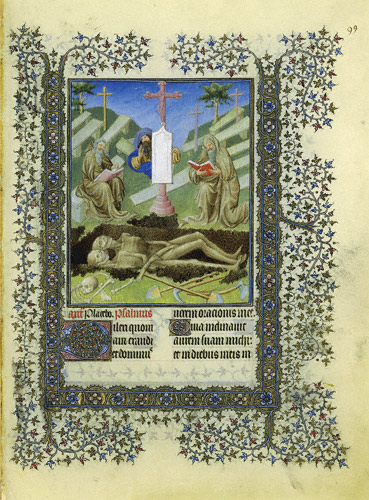

"This mysterious cemetery scene accompanies the section of the Belles Heures known as the Office of the Dead, a standard feature of a book of hours. By praying the Office of the Dead on a daily basis, the living commemorated departed loved ones and sought to help them enter heaven more quickly. The text's value was heightened by the ubiquity of death in the Middle Ages, when disease, warfare, poor health care, and tremendously high infant mortality rates led to shorter lives. In this illumination, a prophet emerges from behind the pink crucifix and points to the bodies in the grave. The corpses appear to not yet be buried, but they have decomposed nonetheless. Two men read or pray by the graveside. The meaning of the scene is unclear...." read more: http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/belles_heures/

If art can be said to reveal the spirit of an age, then the decorated pages of the “Belles Heures” of the Duc de Berry are proof only that the fifteenth-century in France was a period of extraordinary contrasts. Certainly the sparkling miniatures of the saints and angels seem to have little to do with the mundane horrors that people faced. By all accounts, the dawn of the fifteenth-century was a time of chronic war, injustice, misery, and pestilence.

The Belles Heures is the first of two Books of Hours with miniatures by the Limbourg brothers, artists in the service of the Duc de Berry. Rich in marvelous and often bloody detail, the lives of the saints made a Bok of Hours enjoyable as a storybook as well as a spiritual guide. Since there was no prescribed iconography for a Book of Hours, the artists who illustrated them were free, within the confines of the patron’s wishes, to introduce new subjects and designs. The person commissioning these works knew the result would be a truly original piece of art.

"For his most personal Book of Hours, the Belles Heures, the Duke of Berry engaged the most famous book painters at this time, the Limbourg brothers Pol, Herman and Jehanequin. All the 172 miniatures of the Limbourg brothers have a vivacity and colorfulness that secure for them a place in the history of illumination. Every miniature and every page of the text of the Belles Heures of Jean Duke of Berry is surrounded by decorative filigree scrollwork with up to 500 gold glowing ivy leaves. But even this sumptuous decoration is excelled by the playfully arranged luminous elements on the prime pages introducing the Office of the Virgin and the Office of the Dead. This luxurious decoration, which is extraordinarily exuberant even for a Book of Hours from the ducal library, achieves perfection in the use of countless ornamented initials that extend over one or several lines and are painted in red, blue and glowing gold - the colours of the ducal crest..." Read More: http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibits/illuman/15_02.html

Not all the miniatures of the Belles Heures are religious in nature. Scenes from the secular life- threshing of wheat, trampling of grapes, slaughtering of a pig- mark the seasons on the pages of a calendar. The first of the two portraits of the duke depicts him in a splendid blue robe and kneeling at prayer in his private oratory. A grand and vigorous seignior, he appears to be in his late thirties or early forties. The Limbourg brothers must have known the value of flattery, for the duke was about sixty-five at the time. Since the portrait faces one of Jeanne de Boulogne, Berry’s second wife, then in her twenties, youthful appearance was important.

In 1466 another scourge of the age- epidemic disease- apparently took the lives of all three of the Limbourg brothers. Within six months, their patron was himself dead at the age of seventy-five. His vast collection was dispersed, of which not much is known except in the nineteenth-century it passed into the hands of Baron Edmund de Rothschild and later to The Cloisters in New York.

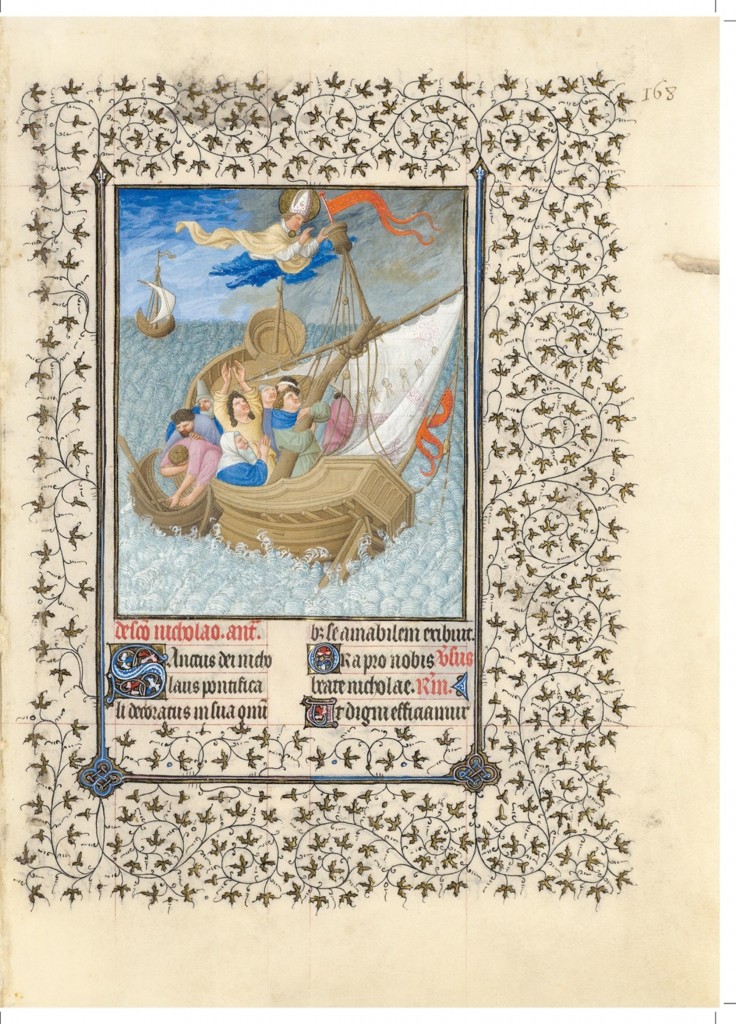

"Suffrages of the Saints Saint Nicholas Saves Travelers at Sea, Folio 168r In one of the most dramatic scenes in this section of the manuscript, a ship veers wildly out of control in a stormy sea, its mast already broken and the sailors reacting emotionally. Saint Nicholas grasps the ship’s crow’s nest to steady the vessel, and already the stormy sky at right is resolving to the serene blue at upper left. The corkscrew waves painted in silver, white, and blue shimmer on the page." read more: http://blog.metmuseum.org/artofillumination/manuscript-pages/folio-168r/

ADDENDUM:

COMMENTS

COMMENTS