A preoccupation with mystery, violence and the irrational was always present in Goya’s art. As the years passed, casual observations of the foibles and horrors of the world were transfigured into a vision of life that came to dominate his work.

As he entered his sixties, Goya’s isolation from the world in which he still seemed to move so freely was increased by factors other than his deafness. In the final stage of its dissolution as a great power, Spain was in a state of political and social chaos. The libertarian idealists made temporarily effective forays against the regime, and were repeatedly and mercilessly repressed. Some of Goya’s friends were imprisoned or exiled. Goya had not yet made any overt political statements in his art and was in an equivocal position.

Alan Woods: Spain was now a seething cauldron. With the connivance of Maria Luisa, the adventurer Godoy effectively took power in Madrid. The crown prince Ferdinand conspired to oust Godoy with the support of the people and most of the nobility. He also tried to establish good relations with France. As part of the plan, Ferdinand was to marry a "princess" drawn from the Bonaparte clan. In 1808, on 17th March, in Aranjuez, the playground of the Spanish monarchy a few miles from Madrid, the whole thing exploded. An angry crowd, with typical Spanish impulsiveness, stirred up by Ferdinand's agents, poured out onto the streets, and burst into Godoy's mansion. While the mob ransacked his home, the prime minister lay cowering in a roll of matting. Godoy only just managed to save himself by the intervention of the Guard. Though the immediate target was Godoy, the real motive was popular discontent at the presence of French troops in Spain. read more: http://www.marxist.com/ArtAndLiterature-old/goya_1.html image: http://www.artsyferret.com/?p=45

As the first artist of the court,working primarily as a portraitist, he was perfectly safe because his position did not require him to turn his art to political or propagandistic ends. But as a draftsman and print maker, observing society from a libertarian point of view , he could comment only in opposition to the ideals of his royal patrons. The result was that Goya began to work for himself and his friends alone.

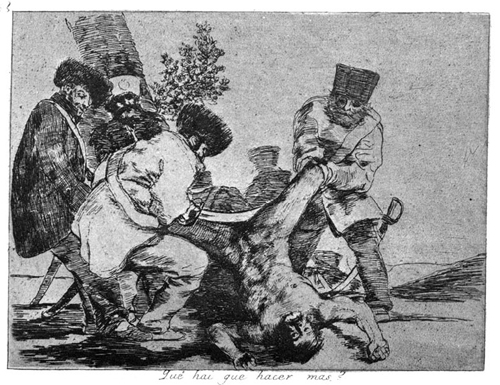

The Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1808, with its guerrilla excesses, supplied Goya with the most appalling direct evidence of man’s capacity to degrade himself through violence. Between the year of the invasion and about 1814, he created a second series of etchings with aquatint, “The Disasters of War”, scenes of sickening butchery punctuated occasionally with political allegories. Their publication during French occupation or Spanish alliance with the French was of course impossible; the plates were not printed until 1863. Except for the photographs by Matthew Brady of the American Civil War, which were just then appearing, they had no equal in their treatment of war for what it is, without overtones of the picturesque or the ideally heroic.

"It is important to note that if it had been left to the royal family and the Spanish ruling class, Napoleon would have occupied Spain without the slightest difficulty. The Bourbons and the aristocracy behaved in the most abject manner, fawning and crawling on their bellies before the French. On June 7th 1808, king Joseph received at Bayonne a deputation of the grandees of Spain and was addressed by the Duke of Infantado, Ferdinand VII's most intimate friend, in the following terms: "Sire, the grandees of Spain have at all times been celebrated for their loyalty to their Sovereign, and in them your Majesty will now find the same fidelity and adhesion." The royal Council of Castile assured the French usurper that "he was the principal branch of a family designed by Heaven to reign". And so on and so forth. However, the destiny of Spain was immediately taken out of the hands of the cowardly and treacherous nobility. The masses erupted onto the scene to save their country from the foreign invader." read more: http://www.marxist.com/ArtAndLiterature-old/goya_1.html image: http://graememitchell.com/blog/goyas-head

Goya’s single direct declaration of his political sympathies was made in two paintings done during the short-lived liberal Regency of 1814, only a matter of weeks before it fell to the reactionary Ferdinand VII. In “The Second of May , 1808″ Goya commemorated an uprising in the streets of Madrid, when citizens armed only with sticks, stones and knives attacked the Egyptian cavalry that Napoleon had sent to support his brother’s puppet throne.

The picture is a melee of forms and colors devoid of any hint of the classical tradition of history painting, a romantic fanfare more immediately apparent as an exciting battle scene than as a patriotic tribute. But the companion picture, “The Third of May, 1808″ is another matter.

---From an email with a Napoleonic scholar: "I went back and looked over your historical info. and it looks fine to me. I was actually pleased that you mentioned that the Spanish committed atrocities against the French as well in response for their actions. In your discussion of "Great deeds against the dead" I just wanted to mention that Spanish guerrillas and peasants were also known to have frequently unearthed dead Frenchmen and mutilated their corpses. My other comment concerns your discussion in "the Third of May." You mention the dissatisfaction that many Spanish intellectuals had with Charles and Ferdinand and you say that these two monarchs ruled unsuccessfully. Actually one of the major problems that the Spanish intellectuals had with their kings was that they refused to give their subjects a constitution (a major goal of liberals in the early 19th century).---Read More: http://eeweems.com/goya/disasters_plate_32.html

The uprising of may 2 had been immediately quelled, and on the following day, batches of suspects were rounded up more or less indiscriminately, hustled off to the fringe of the town, then unceremoniously shot. Goya show half a dozen victims kneeling in a group among the bloody corpses of their fellows, while other citizens, waiting in a file to die, cast down their eyes in horror.We are at that split-second of firing. One of the condemned men hides his face; another, a monk, prays; two others overcome their terror to glare at the riflemen. The group, and the picture, comes to its climax in the figure of a young man flinging both arms upward in defiance. A man may be easy to kill, his gesture says, but the human spirit in far more unquenchable.

---according to Kenneth Clark, "by a stroke of genius Goya has contrasted the fierce repetition of the soldiers' attitudes and the steely line of their rifles, with the crumbling irregularity of their target." A square lantern situated on the ground between the two groups throws a dramatic light on the scene. The brightest illumination falls on the huddled victims to the left, whose numbers include a monk or friar in prayer. To the immediate right and at the center of the canvas, other condemned figures stand next in line to be shot. The central figure is the brilliantly lit man kneeling amid the bloodied corpses of those already executed, his arms flung wide in either appeal or defiance. His yellow and white clothing repeats the colors of the lantern. His plain white shirt and sun-burnt face show he is a simple labourer. ---

d more: http://www.museumstuff.com/learn/topics/The_Third_of_May_1808::sub::The_PaintingADDENDUM:

Jim Lane: I categorised The Third of May as a “journalistic/propagandist” work citing only Picasso’s incredible mural-size Guernica (done some 130 years later) as being on a par with Goya’s painting. I think I was right on that count, but on the subject of journalistic/propagandist painting, I was wrong. Goya, being a Spaniard, could look back on some of Velázquez’s work for some inspiration along this line, but the real experts on this sort of thing were the French. French art is literally “full of it,” (pun intended).

I guess where I erred was in thinking of The Third of May mostly in journalistic terms, which, in large part, as the title would suggest, was certainly the intention of the painter, very much akin to a news photographer snapping a picture for the front page of The New York Times. However the painting was commissioned by the Spanish court for no other reason than to remind the populace surviving the regime of French puppet ruler, Joseph Bonaparte, how brave, loyal, and patriotic were the resistance fighters gunned down by Napoleon’s murderers–pure propaganda. And, it was painted in 1814, some six years after the event so graphically depicted. If that’s “journalism,” it certainly would win some kind of award for procrastination. Maybe it should more rightly be called history painting, though still, it looks and “feels” like “news.” Read More: http://www.humanitiesweb.org/human.php?s=g&p=g&a=d&ID=39 a

The Second of May. Claudio Veliz: When Ferdinand VII returned to the throne in 1814, all those suspected of collaboration with the French--including Goya--were subjected to rigorous questioning. When asked about the well-known award of that Royal Order of Spain, Goya responded that he had indeed received it, but had never worn it. Possibly because of Ferdinand's intervention, the painter was exonerated on the strength of this absurdly lame explanation. The monarch knew and had a reluctant admiration for the painter, having posed for him before his abdication and also in 1814 on his return to the throne, a revealing gesture at a time when Goya was under investigation; according to some reports the King let it be known that although Goya deserved to be executed for treason, he was such a great painter that it was best to let him be. read more: http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-153359671.html

As recently demonstrated by the Balkan bloodshed, the line between journalism and propaganda is terribly tangled…so much so we now call much of such reportage “spin.” The Third of May was spin. But beyond that, it was also a turning point in how wars were painted. In the manner of Nicolas Poussin’s Rape of the Sabines, painted in 1637, for instance, there was much organised chaos and noble posturing but little in the way of bloody horror. Goya chose not only to depict such carnage, but also to emphasise it, over all else. From that point on, whether you call it journalism, history painting, or propaganda, war was painted in red. Eugène Delacroix in his Liberty Leading the People (1830), Manet in his Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868) and Meissonier, in his Siege of Paris (1870), literally seem to have bathed in the stuff. Only Picasso was self-assured enough in his moral outrage to abandon the blood in favour of pathos, and to do so in such a timely manner that, whatever propaganda value Guernica may have had, it certainly wasn’t stale news.Read More: http://www.humanitiesweb.org/human.php?s=g&p=g&a=d&ID=39

http://media.wiley.com/product_data/excerpt/81/14443350/1444335081.pdf

http://www.learner.org/courses/globalart/work/161/index.html

http://www.beamsandstruts.com/bits-a-pieces/item/227-art-contemplation-in-goyas-greatest-scenes

COMMENTS

COMMENTS