Its the original Fiat 500. The installation piece by Lorenzo Quinn features an almost 13 foot high child’s hand and forearm. Like a toddler giant Nephilim playing with a toy.The work alludes to the relationship between parents and their children and represents the independence and freedom Quinn felt when he bought his first car.

”After being displayed in Abu Dhabi and Valencia, Spain, the sculpture has now been installed on Park Lane, a swanky stretch of road in central London characterized by a number of five-star hotels and high-end automobile dealerships. This certainly ought to put things into perspective for the next noble gentleman shopping for a new motor car.” Read More: http://www.autoblog.com/2011/01/25/lorenzo-quinns-vroom-vroom-sculpture-arrives-in-central-londo/ a

Read More: http://artyouknow.com/2010/06/ivam-celebrates-formula-1-grand-prix-with-installation-by-lorenzo-quinn/''Vroom Vroom represents part of my independence, my freedom, my personal growth. This was the first car that I bought with the money I made from my early works. It was hard work, but the purchase was satisfying. I had obtained something I really wanted through my own effort. I did not depend on my parents anymore, I was grown up. This car has been my talisman. One day a client visiting my studio said "that car is so small, it looks like a toy." This comment made me think: often the only difference between a child and an adult is the price of the toy. Actually, this car was a toy to me, I worked hard to get it, and once I had it I enjoyed it like a child would. I think that over the years, social pressure makes us lose our innocence and excitement about the little things. We end up forgetting the child within.This sculpture represents the innocence and excitement about the little things that make us happy.’ Read More:

“The wicker beach chair just inside the entrance of The Casements looks almost quaint, an upended picnic basket. Yet from this throne, in the dawn of the 20th century, Standard Oil titan John D. Rockefeller Sr. watched his millionaire friends race automobiles down the broad, hard-packed sands of Ormond Beach.

Due east down Granada Boulevard, the Birthplace of Speed park marks the location of the Hotel Ormond Challenge Cup, a pioneering 1903 match between autos built by Alexander Winton and Ransom Olds. Olds’ spidery-looking racer, “Pirate,” was described by some as a “bedspring on wheels.” Winton, driving his own oblong “Bullet,” barely won, officially achieving 48 miles per hour.The oil magnate, otherwise a no-frills and frugal man, had a serious fascination with the automobile. Rockefeller was delighted when friend Henry Ford gave him the first Ford V-8 to come off the assembly line in 1931. Read More:http://findarticles.com/p/news-articles/palm-beach-post/mi_8163/is_20040919/frugal-rockefeller-fascinated-automobile/ai_n51850111/

Read More: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-11615233---Paul Green, president of Halcyon Gallery which is supplying the artwork, said: "This is extremely important for Lorenzo Quinn. We are really looking forward to seeing the public's reaction." Councillor Alastair Moss, chairman of the planning application sub committee, said: "I think that many people feel a fondness and love for their first car which stays with them for a lifetime, and I hope this artwork brings a similar feeling of excitement to the many people visiting the West End." The installation is part of the council's two-year City of Sculpture Festival during which 60 pieces of art donated by galleries and artists will temporarily be on show in the run-up to the 2012 Olympics.

There was a time — the Golden Age of the Automobile in the 1950s and 1960s — when cars were really at the center of American cultural life. The car reflected individuality and status; what you drove told us a lot about who you were, since most cars were not bought on credit or lease. So if your family drove a an econo-box you were condemned to an image less than desirable on the part of your peers. But that has changed, at least in part. Cars for many are a cheap means to get from a to b and the objects of desire have shifted to other classes of goods.

Read More: http://soloroadtrip.com/tripjournal/the-dakotas/''Carhenge which replicates Stonehenge, consists of the circle of cars, 3 standing trilithons within the circle, the heel stone, slaughter stone, and 2 station stones, and the Aubrey circle, named after Sir John Aubrey who first recognized the earthworks and great stones as a prehistoric temple in 1648. The artist of this unique car sculpture, Jim Reinders, experimented with unusual and interesting artistic creations throughout his life. His desire to copy Stonehenge in physical size and placement came to fruition in the summer of 1987 with the help of family. Thirty-eight automobiles were placed to assume the same proportions as Stonehenge with the circle measuring approximately 96 feet in diameter. The honor of depicting the heel stone goes to a 1962 Caddy.''

The first American artist to grapple with this concept of the car was John Sloan. An avowed socialist, Sloan saw the car within the scope of Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class and the motorized vehicle was an accessory in the strivings of these newly emerging wealthy classes and quickly led Sloan to make the connection of the car as central device in the American dream and a symbol of celebrity and wealth.

In his “Indian Detour” of 1927, Sloan played up the parody and ridicule in a telling reversal of history. Sloan had always seemed to recognize the absurdity and find the irony in the association of car travel with the frontier spirit, when it a metaphor for the destruction of it. He saw it as a misguided romantic notion of leaving civilization behind to explore virgin territory. Here, buses, tourists, and travelers surround a group of Santa Fe Indians while performing a ritual dance. No longer are the wagons surrounding migrating settlers for protection as was the case in the ni

enth- century; its now a show of strength as mechanized version of the earlier genocide.

Indian Detour. ---A satire of the Harvey Indian Tour. Buses take the tourists out to view the Indian dances, which are religious ceremonials and naturally not understood as such by the visiting crowds” (Dart 79). This scene is identified as the corn dance at Santa Dominga Pueblo, in an updated article from the Santa Fe New Mexican of August or September 1936. read more: http://keithsheridan.com/sloan.html

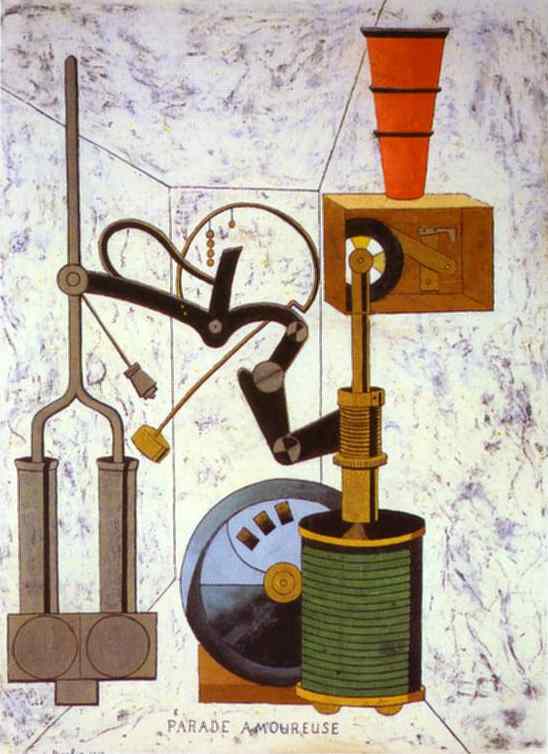

The most significant contribution of establishing the iconography of the car in twentieth century American art can be attributed to European painter, Dadaist, and car freak, Francis Picabia. He introduced the image of car parts into his art while in America in 1915, utilizing these forms in highly personal ways that showed mechanical symbolism as object and machine portraits.

---European émigré artists in other fields had noted the significance of machinery to early 20th c. America., and several tried to incorporate it into their art. One such was Francis Picabia, who attempted to derive a “machinist” style of hard-edged precision to reflect the symbolism of the machine: I have been profoundly impressed by the vast mechanical development in America. The machine has become more than a mere adjunct of life. It is really part of human life… perhaps the very soul. ( Nick Lambert) Read More: http://thesis.lambertsblog.co.uk/?page_id=121

Later, a view of the auto factory that was more attuned to its violent potential as source of materialism was the Diego Rivea murals in Detroit .

"Henry Ford’s son Edsel commissioned the Rivera mural in the 1930s and was met with some criticism at the time. It was a bit odd that the leading industrialist of the time would select an avowed Marxist to depict the inner workings of the Ford Rouge River Plant and its relationship to the city and its people. The mural was considered scandalous for the depictions of nudity, religious iconography, and multi-racial workforce. It represented the merging of man and machine, steel and flesh in a gritty depiction of the life of the common worker. A Detroit News editorial at the time of the original unveiling called the murals “coarse in conception … foolishly vulgar … a slander to Detroit workmen … un-American.” The writer urged that the murals be destroyed. The Ford Family, however, would not allow it, and understood the symbolism of the relationship of industry to the lifeblood of the city. ...read more: http://www.weblogtheworld.com/countries/northern-america/ford-reception-at-the-detroit-institute-of-arts/

ADDENDUM:

Andrew Graham Dixon: The original shock value of Picabia’s mechanical allegories is impossible to recapture, almost a hundred years later. But this was daring and disconcertingly original work to have created in the second decade of the twentieth century – dealing not only in the taboo subject of sex, but treating it purely as process and mechanism, without any consoling reference to love or indeed any other emotion. In New York, Picabia and Duchamp met and befriended Man Ray, who shared their sardonic fascination with machines and brought it into the realm of photography. Man of 1918 is characteristic: a photograph, blotched by time, of a hand-operated food whisk hung at a suggestive angle on a wall.

"The mural above is painted of a Ford Motor Car Factory in Detoit, Michigan. It reflects on the original operations of the factory during its hay-day. A blast from the past. It is referenced in a book I just read about sustainability called Cradle to Cradle. The authors of the book helped Ford revitalize their campus of factories into environmentally efficient and responsible buildings. And that effort in turn inspired Ford to reassess their building guidelines for all of their factories across the globe." read more: http://charliebabbage.blogspot.com/

But it was Duchamp, ultimately the most influential of the three artists, who created the most aggressively unconventional metaphor of human beings as sexual automata. He called the work The Large Glass, or The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even and he laboured on it for eight years before leaving it unfinished in 1923. Read More: http://www.andrewgrahamdixon.com/archive/readArticle/548 a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS