Very few paintings in the history of art have so puzzled viewers as Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. Only now perhaps, in our present new age of folly, can its meaning be made clear. Today we take a brief look at the right panel of Bosch’s triptych called Hell. …

The panel on the right, balancing Paradise, is hell. It is not the conventional medieval hell, where apelike devils torment sinners with instruments used by human torturers- pincers, hot irons, and boiling oil. Nor is it an organized hell like that of Dante, which is the work of Divine Reason, constructed according to the three Aristotelian categories of wrongdoing: Incontinence, Violence and Malice. It is all like a drug dream, a nightmare, or the interior of a manic’s mind. This one of the ruling ideas of Hieronymus Bosch: that health, virtue, and heaven are calm, orderly and reasonable, while illness, sin and hell are wild, random, and senseless.

"His paintings depict a weird world full of grotesque and horrifying creatures, giving vivid form to the fear of Hell that haunted the medieval minds of that time. " Read More: http://xycolsen.blogspot.com/2009/03/art-of-hieronymus-bosch.html

Beside’s Dante’s Inferno, there are many other visions of hell that have been described in considerable detail by men of the Middle Ages. But, in all such descriptions, it appears that hell, in its essentials, is logical and systematic. It is a kingdom. Its citizens are the devils, who oppress the damned souls as the bad nobelemen and their soldiers oppressed the peasants in earthly life. Its monarch, Satan, supernaturally huge and infernally hideous, reigns at its center, eternally tormented by god’s decree, and himself tormenting the worst of human sinners, chewing and mangling them.

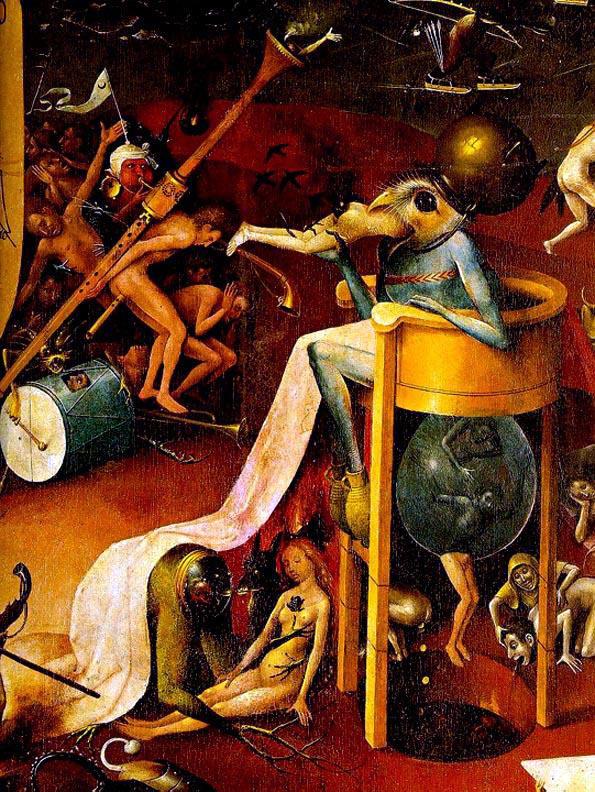

"The right panel illustrates Hell, the setting of a number of Bosch paintings. Bosch depicts a world in which humans have succumbed to the temptations of the devil and reap eternal damnation. The tone of this final panel strikes a harsh contrast to those preceding it. The scene is set at night, and the natural beauty that adorned the earlier panels is noticeably absent. Compared to the warmth of the center panel, the right wing possesses a chilling quality—rendered through cold colourisation and frozen waterways—and presents a tableau that has shifted from the paradise of the center image to a spectacle of cruel torture and retribution. In a single, densely detailed scene, the viewer is made witness to cities on fire in the background; war, torture chambers, infernal taverns, and demons in the midground; and mutated animals feeding on human flesh in the foreground. The nakedness of the human figures has lost all its eroticism, and many now attempt to cover their genitalia and breasts with their hands." Read More: http://viewfromthebow.blogspot.com/2010/10/garden-of-earthly-delights.html

In such a hell the fiends all do what bad human beings would do if they had almost infinite power and ingenuity. They appear to be using their mind to inflict pain; they are jailers, interrogators, torturers, working under a system of law and giving evil for evil. But for Bosch, hell is the abrogation of the intellect. In his hell, very little happens for any intelligible reason- except that sometimes a sinner is apparently punished by the worldly device that led him into sin, as when a soul who loved profane music too well is crucified on a harp, or when gamblers are pinned to the gaming table….

make of Bosch's furious symbolism and dark visions. What does a master artist of the 15th century have to say to his large public in the 20th century? There is little doubt about his popularity. Some of his monstrous images have become clichés, almost camp. Few paintings have had the kind of attention that has been lavished on the Garden of Earthly Delights. Together, the three panels of this triptych measure nearly 13 feet in width and a little more than 7 feet in height. Read More: http://www.stanleymeisler.com/smithsonian/smithsonian-1988-03-bosch.html

Meisler: Yet for Bosch and the medieval mind, this world was brimming with symbols of sin – with water birds and fish and ripe strawberries to signify lewdness and lust, with evil crying out for damnation. As punishments, Bosch meted out some of the most terrible tortures ever devised by the human imagination. Sinners are strung on a harp, crushed between a lute and a book, abducted by beasts, severed at the neck, dipped into slime, swallowed by a bird, violated by a flute, kissed by a pig, cut open by swords, chewed by dogs, drowned in seas of fire. No one escapes; no one is saved. A modern viewer can not help feeling anguish and anger at punishment that seems so enormously out of proportion to the sins.Read More: http://www.stanleymeisler.com/smithsonian/smithsonian-1988-03-bosch.html

…But the monarch of Bosch’s hell is not an angel in reverse, turned black and equipped with bat wings, nor, like Dante’s Satan, a three-headed antithesis to the Holy Trinity. It is a monster in which nothing is human but the face, and that is not evil but vacuous. Its legs are dead trees, hollow and stripped of bark; its feet are ships in water, one nearly capsizing. Its body is a thin, empty eggshell inhabited by a few unconcerned figures and one beast. Its head is not a skull with a crown, but a flat disk surmounted by a bagpipe, around which little monsters, not very scary ones, lead sinners.

Meisler:A more recent interpretation of the triptych is gaining academic attention. Laurinda Dixon of Syracuse University, who has studied picture books and scientific manuscripts of the 15th century, sees the painting as an allegory of the alchemical distillation process. Alchemy was a philosophy as well as a legitimate science of the time. Among its practitioners were physicians and pharmacists and, less often, the charlatans and magicians who claimed to make gold from base metals. Throughout the triptych, says Dixon, alchemical symbols can be found. In the center panel, the red balls represent the perfect medicine, the elixir of life....Read More: http://www.stanleymeisler.com/smithsonian/smithsonian-1988-03-bosch.html

A subaltern demon is punishing gluttons, which we can tell because he wears a cooking pot for a crown and beer jugs for shoes, He eats his victims alive and then excretes them into an open latrine. This painful and a little revolting, but it is also ridiculous, and even in a black humorish way; kind of funny. Bosch makes it even more comic by adding a silly looking man to vomit into the mess and, anticipating Freud’s identification of avarice with

childish collection of feces- by making a sinner void gold pieces into it from his anus.

---Literary and visionary sources were likely an important source for Bosch's imagery. One may have been the Dominican visionary, Alain de la Roche, who preached in the Netherlands. His ideas were not unusual for fifteenth century religious sentiment, full of sexual imagery. He preached about "beasts personifying the sins of the flesh, equipped with fearsome genital organs and belching streams of fire whose billowing smoke darkened the earth; He saw the meretrix apostasiae, the whore of apostasy, spawning apostates, devouring them, vomiting them up again, then embracing, fondling them like a mother." (Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages) Additionally, there was the Flemish theologian, Dionysius van Rijckel, founder of the Christian monastery at Bois-le-Duc. He sought, along with other clergy, to put the fear of God into the people, threatening eternal torture in Satan's inferno. Sinners would struggle to escape as they burned in Hell, "groaning and screaming in never-ending pain".---Read More: http://solomonsmusic.net/Bosch_frame.htm

Although the demon is gross, he is neither large nor formidable, and he is avenging only one particular sin. He is not the monarch, for the monarch is the central monster. The one follower of Bosch who understood him best also placed a fragile impotent being like Bosch’s Tree Demon at the central regnal point of hell: Pieter Bruegel in “Dulle Griet”. Bosch means that Satan, after his fall, lost nearly all his godlike semblance and all his power; only the subordinate demons remain active.

Bruegel. Dulle Greit. "The subject matter of Bruegel's compositions covers an impressively wide range. In addition to the landscapes, his repertoire consists of conventional biblical scenes and parables of Christ, mythological subjects as in Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (two versions), and the illustrations of proverbial sayings in The Netherlands Proverbs and several other paintings. His allegorical compositions are often of a religious character, as the two engraved series of The Vices (1556-57) and The Virtues (1559-60), but they included profane social satires as well. The scenes from peasant life are well known, but a number of subjects that are not easy to classify include The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (1559), Children's Games (1560), and Dulle Griet, also known as Mad Meg (1562). " Read More: http://www.navigo.com/wm/paint/auth/bruegel/

COMMENTS

COMMENTS