Vaudeville. Vaudeville, from the height of its appeal to its demise (1870-1930) remained a mass entertainment firmly planted in the lowbrow. Beneath vaudeville was burlesque which occupied a narrow band that teetered towards pornography and back to decadence. But lowbrow is an ambiguous term within the American context; since for a European it symbolizes dislike that neglects the richness of American culture; you cannot evaluate American art by the standards of European modernism. In a vaudeville show you could have everything: from the puritanical to the licentious, from the patriotic to the anarchistic; from worshipers of wealth to humble egalitarians.Vaudeville personified the American idiom of violence between intractable forces: empathy and superiority, identification and alienation.Vaudeville tells a great deal about comedy, an ability of a culture to step outside itself in a nation that is not the hallowed melting pot or mosaic but one huge ethnic variety show crammed to the brim with an amalgam of dialects, manners and differing motives.

Bill Bojangles Robinson. ---Using young black children in vaudeville acts was popular and represented a unique employment opportunity for talented kids. They usually sang and danced, and occasionally played musical instruments for the dimes and quarters he would make in beer gardens and burlesque houses. Orphaned shortly after his birth in 1878, he was raised by a grandmother for a few years. Little is known about his early life, but considering the time, he likely received little, if any, formal education and certainly no dance lessons. He performed on the black circuit for years before moving to Keith and Orpheum circuits, but never wore blackface like some white and many black singers and dancers did. He moved into film during the early talkies, gaining international fame for his scenes with little Shirley Temple. He was the one who taught her to tap dance. There are many examples of his dancing from the Thirties and beyond on YouTube, but none from the vaudeville era. ---(Mary Miley) Read More:http://marymiley.wordpress.com/category/vaudeville/

Vaudeville evolved from the minstrel show which drew much of its energy and appeal from the interaction of the wise-cracking, lowly end-men and the dignified, usually pompous, interlocutor. In this, it embodied the form of American comedy termed by Constance Rourke as the “Yankee fable,” the untrustworthy narrator whose protagonists were popular oracles, yet could have a dark, murky side with origins draped in some mystery, as seen in Herman Melville’s The Confidence Man; the American who can constantly change identities and reinvent themselves. These marginalized but quick-witted figures speak up for the common man in encounters with their cultural or economic superiors. Its possible that American comedy arose from a new nation’s effort to create an identity for itself in to differentiate from a patronizing Old World, but the liberty to change identity and travel without restriction should not be underestimated. The British viewed their former colonial subjects as semi-savage buffoons. Americans admitted as much, but rejoined by giving that comic figure a con artist’s wit and a unique bravado and boldness.

Adele and Fred Astaire.Gilbert Seldes:The application to vaudeville is immediate, because vaudeville is considered on Broadway as the grave of artistic reputations. An actor of established prestige may venture into vaudeville; he usually makes his audience feel exactly how far he has condescended to appear before them and accept, even if he doesn't earn, a salary three times as great as usual; but the actor in the middle distance very well knows that if he goes into vaudeville he is digging his own grave, because there is a stigma attached to the two-a-day. Vaudeville players, in short, are not entitled to "the vestments of refined society." About every ten years the corrupt desire to be refined takes hold of vaudeville itself; but it dies out quickly and vaudeville remains simple and good. Read More:http://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper/Seldes/damned.html image:http://jazzagemusic.blogspot.com/2009/09/september-1st.html

Ultimately, comedy is about our needs, finding a place in the world, and how we cooperate or enter into conflict with people just as obsessed with our own own desires. Ed Folsom: (Ronald )Wallace’s general thesis is that American poetic humor is based on various appropriations of and conflations of the two ancient comic types, the eiron and the alazon. Following Constance Rourke, Wallace equates the selfdeprecating,

witty eiron with the American “Yankee” and the boastful, posing, bragging, foolish alazon with the “Kentuckian” or tall-tale backwoodsman. Emily Dickinson, with her “silence and frugality” becomes the Yankee poet, while Whitman with his “boast and blab” becomes the great poet of the backwoodsmen. With an undeveloped nod toward a third character (the minstrel), Wallace sets up a tradition of American poetic humor based on the two main types: “Backwoods humor made people feel big enough to deal with a terrifying new country; Yankee humor made

them feel small enough to view themselves in proper perspective” . He explores the subtle ways that each of these roles undermines itself, laughing at its own image while simultaneously using that image for positive results. Eventually Wallace demonstrates how our best poets use both the eiron and alazon in a charged dialogue; in Whitman’s poetry, Wallace proposes, the eiron is “an offstage voice to which Whitman

responds throughout the poem” , the voice of conventionality, reason, civilization, finally the voice of the implied reader whom Whitman (as ironist, satirist, and parodist) has to cajole, blast, and bluff out of deadening habits of mind: “The implied dramatic conflict between Whitman and the conventional reader helps structure the comedy” Read More:http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/wwqr/pdf/anc.00443.pdf

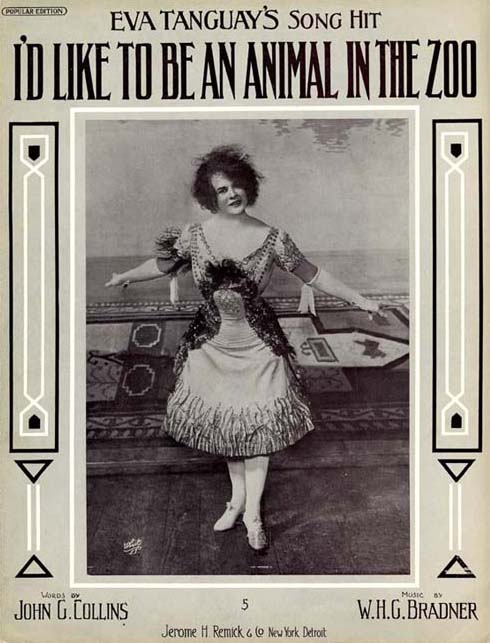

The girl who made vaudeville famous, Eva Tanguay was larger than life. She earned the admiration of Aleister Crowley, who called her "the soul of America at its most desperate eagle-flight...the perfect American artist...ineffably, infinitely, sublime." Shocking for her day and age, she wrote her own songs, many of them odes to and about herself. Some were shockingly explicit for the time, with titles like "Go As Far As You Like, Kid." From an article on Slate: If you read the press and popular literature of the first quarter of the 20th century, Tanguay is inescapable. Edward Bernays, the celebrated "father of public relations," called Tanguay "our first symbol of emergence from the Victorian age." The journalist and playwright George Ade dubbed Theodore Roosevelt "the Eva Tanguay of politics." One of her hits was titled "They'll Remember Me a Hundred Years From Now." To Tanguay's contemporaries, it must have seemed less like a boast than a foregone conclusion. Read More:http://www.enjoy-your-style.com/weird-women-musicians.html

Many of the specialty acts, in fact, deliberately mocked artistic or intellectual pretensions: witness the proliferation of novelty turns in which classical melodies were performed on the musical saw, pushcart peddlers spun rags into beautiful pictures, and tramp comics delivered readings from Shakespeare. Although a few of burlesque’s more talented hits managed to move up successfully to vaudeville, none of vaudeville’s stars ever graduated into serious theatre. Some, like the headlining monologist George Fuller Golden, may have wished secretly to leave variety, but the public to whom he had become so familiar as the raconteur of the popular “Casey” stories would never permit him to assume a more self-fulfilling role. Golden himself was a lover of poetry and an avid reader of the classics. Like so many of West’s thwarted artist figures, he always regretted that to make a living he had to play the buffoon, or as he expressed it, “don the ass’s head.” Read More:http://www.compedit.com/michaels1.htm

---stewart:Over the course of a couple of hours a vaudeville audience might encounter singers, comedians, musicians, dancers, trained animals, female impersonators, acrobats, magicians, hypnotists, jugglers, contortionists, mind-readers, and a wide variety of strange uncategorizable performers usually lumped into the category of “nuts.”---Read More:http://www.splicetoday.com/music/vaudeville-s-back image:http://www.ipernity.com/doc/57114/3985187

Centrally, Vaudeville is a study of national character, society’s mirror that viewed us as compulsive, combustible performers and monologuists, continually dramatizing and mythologizing ourselves; always perfecting our personas ; turning our character or others into identifiable types and then translating these types into legends;then appropriating the legends into new composites.All while turning conflicts into wisecracks and traumas into farcical tall tales. Once Hollywood was established the American comedy accelerated its employment of fantasies of youthful conquest and power. A nation of comics is also linked to the notion of a society of triumph seeking egoists, and the jump from comedy and farce to the altar, marriage and capitalist, or money driven enterprise of family is not tenuous, but almost social engineering or permitted cultural spontaneity.

What may be distinctly American is its continuing obsession with ethnic and racial comedy. It may have begun with Yankees and the Native peoples, then devoured and regurgitated every group that found its way here from every corner of the globe; a battle of hegemony, standardization, homogenization against an equal drive for diversity and group identity.

June Havoc. Seldes:The whole of the material must be subsumed in the whole of the presentation, every page has to be written, every scene rendered, every square inch of the canvas must be painted, not daubed with paint. It is, of course, obvious, that the responsibility in this case is exactly that of the major arts. It is at least tenable that in this case, as in the major arts, the responsibilities are fulfilled. And nothing could be more illuminating than the moments in vaudeville when the tricky and the bogus appear. I face here willingly the protest of intelligent men and women who have gone to vaudeville to see or hear one turn and have sat through some of the dreariest aesthetic dancing,' have heard the most painfully polite vocalism, have witnessed "drama." If vaudeville requires half of what I have said, how do these things get in and get by! Largely as a concession to debased public taste. Note well that all the culture elements in vaudeville, the dull and base and truly vulgar ones, are importations. The dance appropriate to the vaudeville stage is the stunt dance; its Proper music is rag

or jazz; the playlet which belongs to it (witness the success of A Slice of Life) is burlesque. Yet like every other popular art in America, vaudeville is required, by the tradition of gentility, to be cultural; and its dull defenders often make it their boast that it does ...Read More:http://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper/Seldes/damned.html image:http://allanellenberger.com/book-flm-news/june-havoc-obituary/

ADDENDUM:

Jody Rosen ( Slate):Tanguay’s breakthrough came in 1904, in the musical comedy The Sambo Girl. Playing the lead “brownface” role, she stole the show with a new song, a lurching mid-tempo ballad by songwriters Jean Lennox and Harry O. Sutton. The tune was not written expressly for Tanguay, but it may as well have been. For the rest of her career, she merely enlarged on the character-sketch in “I Don’t Care”: a madcap woman on the verge, trampling the conventions of demure femininity, polite society, and musical theater. “They say I’m crazy and got no sense/ But I don’t care,” Tanguay sang. “They may or may not mean offense/ I care less.” Read More:http://www.slate.com/id/2236658/pagenum/2

The song was broadly comic but shocking nonetheless in 1904, when Victorian notions of female propriety prevailed. Blasting out “I Don’t Care,” Tanguay gave voice to an anarchic feminism that claimed the old stigma of female “hysteria” as a badge of honor—the Victorian neurasthenic recast as a liberated, libidinous 20th-century wild-woman:

I don’t care, I don’t care

What they may think of me

I’m happy go lucky

Men say that I’m plucky

I’m happy and carefree

I don’t care, I don’t care

If I should get the mean and stony stare

And no one can faze me

By calling me crazy

‘Cause I don’t care

---Seventy-one years ago, Constance Rourke published ''American Humor,'' one of the best cultural histories of American comedy we have, and in it she made clear that women had been squeezed out of a comic tradition built on popular writing and entertainment in the 18th and 19th centuries. This tradition was dominated by monologues about being an American man on the move, triumphantly discovering, conquering and renovating a continent. Women appeared only as occasional ''gross counterparts'' of these mythic men: the near-monstrous consorts of Davy Crockett in tall tales; the bumptious termagants (played by men) of blackface minstrelsy...Feminine culture, Rourke wrote, ''rose on the American horizon in a cloud no larger than a lady's book. . . . Obviously social comedy could not develop when women remained shadowy, serious figures.'' Women were assigned sentiment, melodrama and domesticity. We still are. (Margo Jefferson ) Read More:http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9404E2D81F3BF93AA35755C0A9649C8B63 image:http://eva_tanguay.asksolomon.com/

The effect was heightened by Tanguay’s outré appearance and performance style. She had a pudgy face and reddish-blond hair that stretched upward in a snarled pile. (She sometimes dumped bottles of champagne over her head onstage.) She was of average height and a bit lumpy, but athletic; she squeezed herself into gaudy costumes that flaunted her buxom figure and powerfully muscled legs. She delivered her songs while executing dervishlike dances, complete with limb-flailing, leg kicks, breast-shaking, and violent tosses of the head; often, she seemed to be simulating orgasm. Tanguay suffered severe cramps from her performances—backstage, she instructed prop directors to unknot her calves by beating them with barrel staves. She told reporters that her goal was “to move so fast and whirl so madly that no one would be able to see my bare legs.”

Then there was Tanguay’s voice. She sang in a slurred screech punctuated by yaps and cackles, ricocheting seemingly at random between her upper and lower registers. Beneath the hiss of the 87-year-old “I Don’t Care” recording, you can hear the maniac’s grin that Tanguay wore when she sang.Read More:http://www.slate.com/id/2236658/pagenum/2

Read More:http://neoneocon.com/2010/11/08/nicholas-brothers-addendum-art-and-pc-purity/

Read More:http://www.jstor.org/pss/2710096

———————————————————————————–

Gilbert Seldes:I shall arrive in a moment at the question of refined vaudeville, a thing I dislike intensely; there is another sort of refinement in vaudeville which demands respect. It is the refinement of technique. It seems to me that the unerring taste of Fanny Brice’s impersonations is at least partly due to, and has been achieved through, the purely technical mastery she has developed; I am sure that the vaudeville stage makes such demands upon its artists that they are compelled to perfect everything. They have to do whatever they do swiftly, neatly, without lost motion; they must touch and leap aside; they dare not hold an audience more than a few minutes, at least not with the same stunt; they have to establish an immediate contact, set a current in motion, and exploit it to the last possible degree in the shortest space of time. They have to be always “in the picture,” for though the vaudeville stage seems to give them endless freedom and innumerable opportunities, it-holds them to strict account; it permits no fumbling, and there are no reparable errors. The materials they use are trivial, yes; but the treatment must be accurate to a hair’s breadth; the wine they serve is light, it must fill the goblet to the very brim, and not a drop must spill over. There is no great second act to redeem a false entrance; no grand climacteric to make up for even a moment’s dullness. Read More:http://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper/Seldes/damned.html

COMMENTS

COMMENTS