She rarely showed he paintings publicly and refused to put any of her work up for sale. Of course, she came from a wealthy family and didn’t have to sell her art to survive or play the art game with critics and gallery owners. Like Kafka, she left instructions to destroy her art after she died. Florine Stettheimer was much more than an early modernist painter of originality and wit. That “much more” continues to perplex and inspire….

---In 1914, on the eve of World War I, she returned to New York with her mother and two sisters—Carrie and Ettie—and the family settled into an apartment in Alwyn Court on West 58th Street, near Carnegie Hall. There, Stettheimer and her sisters established a legendary salon that was frequented by many of the most important creative people of the time—among them, Marcel Duchamp, Carl Van Vechten, Gaston Lachaise, Sherwood Anderson, Edie Nedelman, Virgil Thompson, Edgar Varese, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Steiglitz and the art critic Henry McBride.--- Read More:http://venetianred.net/2009/07/01/florine-stettheimer-occasionally-a-human-being-saw-my-light/ image:http://www.myspace.com/10858039/photos/1650041#{%22ImageId%22%3A1650041}

Pomposity, dutifulness, the heavy automatic and reactionary response to an implicitly patriarchal infallibility: such are the things which filled Florine Stettheimer with horror. What inspires her with delight is the very opposite of all that is heavy, dutiful, solemn, or imposed by authority. The question can then be posed about the conventional notions of an art of social concern; what is the visual language permitted to articulate this? Must a public art of this kind be solemn, pompous and alienated? On the contrary, can it be personal, witty and satirical? Is it possible for imagination and reality to converge in a lively problematic image of contemporary society? And what precisely are the boundaries between the public and the private and why has such a distinction been made in the creation of art? All these issues are raised, though far from resolved, by the art of Florine Stettheimer.

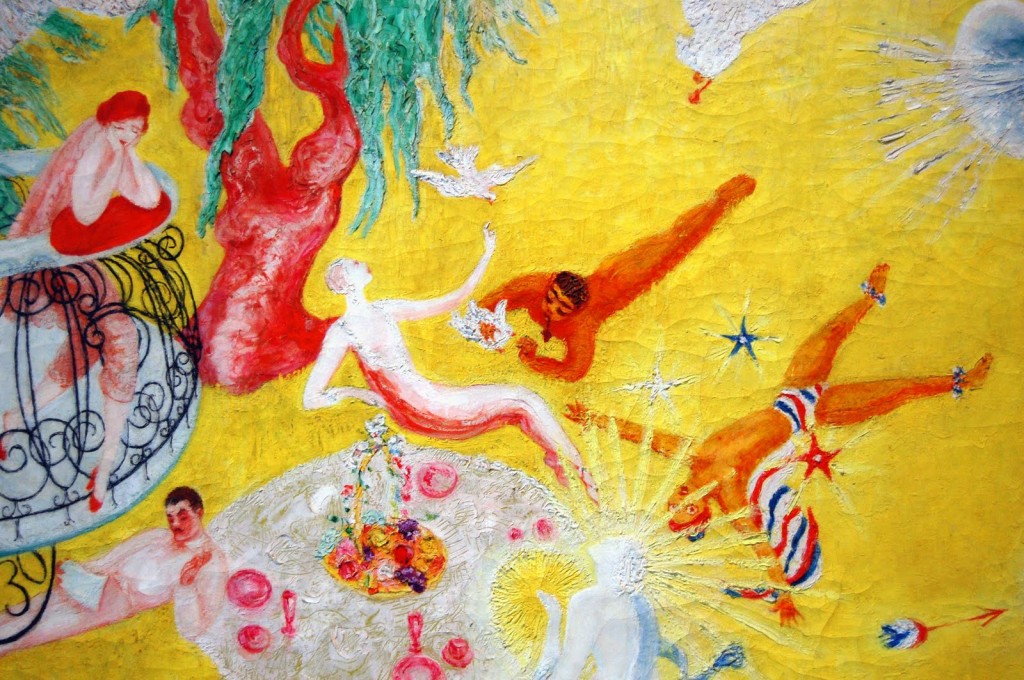

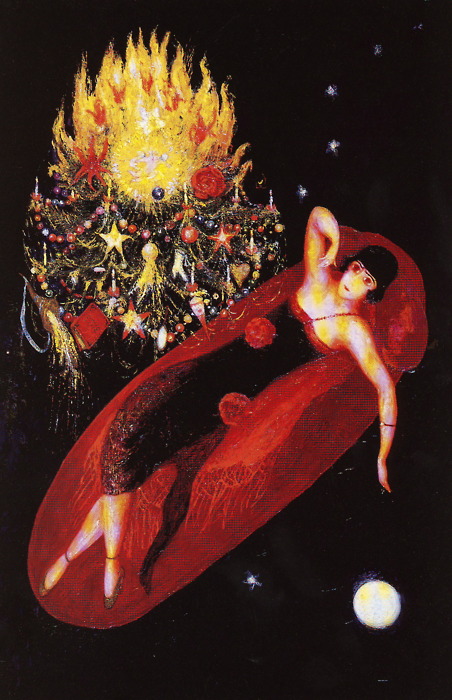

Stettheimer. Love Flight of a Pink Candy Heart. detail. ---In her dazzling and eccentric paintings, with their bold color and openly feminine sensibility, Stettheimer created a unique synthesis of things she studied and loved—one catches glimpses of medieval portraiture, Persian miniatures, Brueghel, early Renaissance painting, Velasquez, children’s art, theater design, Matisse, Surrealism, Symbolism, folk art, fashion illustration, decorative art and interior design. She combines high/low elements in vivid constructions that depict scenes in a non-sequential, dream-like way—she played with perspective and her people and objects often float languidly through a complex universe of multiple narratives that have an allegorical quality. --- Read More:http://venetianred.net/2009/07/01/florine-stettheimer-occasionally-a-human-being-saw-my-light/ image:http://spillyjane.blogspot.com/2011/01/florines-love-flight.html

In getting down to looking at her work in detail, it might be better to view her reconciliation of social awareness with a highly wrought camp vision of life, as only one of a number of paradoxes and contradictions inherent to her nature and situation. A duality explained in that she was an insider and an outsider. She was comfortably wealthy, a giver of parties and friends with many interesting and fascinating people. However, she was Jewish, a very private artist, and a woman artist at that. Also, she was a determined feminist, combined with an equal determination to be feminine in the most conventional sense of the term. Despite the femininity she was capable of voicing her poetry with a quite outspoken and prickly antagonism towards male patriarchy. ( Nochlin )

Marcel Duchamp. Florine Stettheimer.The thoroughly modern Florine Stettheimer is a greater artist than Georgia O’Keeffe. - Roberta Smith Read More:http://leroyspinkfist.blogspot.com/2010/12/florine-stettheimer.html

The most curious piece in connecting the enigma of Florine Stettheimer, our ability to “read” her through her work, is the relation she had with Marcel Duchamp, and his peculiar connection with Raymond Roussel, connections which extend to Dada, surrealism, Tristan Tzara and potentially even to Lenin. There is some kind of hermetic symbolism embedded in Stettheimer’s art; its an affirmative art that somehow subversively has some as yet unrecognized pattern, perhaps to the geometry used by Dali. Her art is crowded, amusing and unorthodox, but beyond the seeming eccentricities is something more substantial.

On the contrary, his subject matter became, in 1912, progressively more precisely focussed. But Duchamp neglected to discuss the matter of Roussel’s impact until thirtythree years after the event, and then, only very briefly; and he is totally silent on the circumstances in which Roussel’s example had its effect – in Munich. Up to his relaunch in the United States from 1942, his modus operandum, and way of life, clearly

did not require any such public declaration. But this neglect, between the Sweeney interview of 1946 and the discussions with Cabanne in the 1960’s, arose, we suggest, for two reasons. The first is the threat to Duchamp’s newly burgeoning identity, as the grandfather of a new kind of avant-garde practice, posed by the insight into his anaesthetic method that assumes a knowledge of Roussel’s. The second is Roussel’s, and Duchamp’s, occult credentials, as a number of events support. For example, in the early forties Duchamp declined to accept the bequest of the mystical portrait Florine Stettheimer had painted of him in the 1920’s. And in the early fifties, Katherine Dreier’s death presented him, as executor of her art estate, with the opportunity to destroy her equally esoteric portrait of him, of 1918, into which he had painted his own portrait in the form of his astral or etheric body; this he did. That there are more cannot detain us here. Read More:http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/902/1/uk_bl_ethos_496515_vol1.pdf

ADDENDUM:

---And this portrait of her sister Effie, in which Henry McBride described her as looking “…wide-eyed, for the mystery of life…as happy a blend of her worldliness and spirituality as any psychiatrist could ask for.”--- Read More:ht

/venetianred.net/2009/07/01/florine-stettheimer-occasionally-a-human-being-saw-my-light/Bloemink:Stettheimer was highly ambitious, a trait she shared with other contemporary women artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo, who also achieved recognition for their work during their lifetime. Unlike them, however, she chose not to have a prestigious partner or husband to guide her professional development. That she was nevertheless able to achieve considerable professional recognition for her work in her lifetime is one of her singular achievements. It indicates the power of her work and her strength of will, both of which were at variance with her public role as a proper social hostess.

Bloemink:that in 1915 Stettheimer had the temerity to display herself thus and to make so pointed a comparison with Manet's Olympia, a prostitute offering her wares for sale. In so doing, Stettheimer aggressively took on the genre of the female nude in Western art history and its gender implications. Her own lushly displayed body in the self-portrait is less the traditional subject of a man's voyeuristic gaze than an exaltation of a woman's experience of her middle-aged body. Undoubtedly the disjunction between art historical traditional expectations and Stettheimer's candid but ironic appropriation of them blinded her contemporaries and other art historians to her true subject matter in the work. Read More:http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=kt5b69q3pk&chunk.id=ch09&toc.id=ch09&brand=ucpress

The radical nature of her paintings, theatrical designs, poetry, and furniture caused Stettheimer’s contemporaries to cite her as one of the most important historians and visual critics of the period between the world wars. However, the contradictions in Stettheimer’s private life thwart all attempts to canonize her. She was a quiet and shy woman—a Jewish spinster who spent her entire life in the confines of her matriarchal family. Stettheimer was never active socially unless surrounded … Read More:http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=kt5b69q3pk&chunk.id=ch09&toc.id=ch09&brand=ucpress

Read More:http://withhiddennoise.net/2010/12/17/florine-stettheimer-crystal-flowers-poems-and-a-libretto/

—————————————————————-

As the artist further acknowledged, Arensberg directly contributed toDuchamp’s material support, particularly by paying his rent. This largesse was supplemented by Duchamp with another job as a librarian, at the Institut Français in Manhattan, or by giving French lessons to Arensberg’s wealthy friends, including Katherine Dreier and the three Stettheimer spinsters, Carrie,Florine, and Ettie. Duchamp’s pay as a teacher was spectacular at a time when the going wage for an exhausting, nine-hour, workday in the automo-bile industry was only $2.50. Both these part-time jobs provided Duchamp with enough money to be independent. Of his desultory linguistic labors, the artist later recalled, “I gave two or three lessons a day, and I probably learned more English than my pupils learned French. I was not a good teacher—too impatient. . . . I could almost live on what I made this way, because every-thing was so much cheaper then. You could live in New York on five dollars a day, and, if you had ten dollars, you were a king.”…

Despite the somewhat disparaging tone of Duchamp’s comments about his generous patron’s cryptographic obsessions, it is unquestionable thatDuchamp himself enthusiastically participated in the very same esoteric activities. Evidence to this effect is provided are four mysteriously inscribed postcards addressed to Walter Arensberg; now called Rendez-vous du Dimanche 6 Février 1916 . . . , this is an ensemble which Dieter Daniels labels a blatantly “kryptographischer Verschlüsselungen.” In 1916, for in-stance, Duchamp also collaborated with Arensberg in the cryptic redoing of an ordinary dog’s grooming comb; relabeled Peigne , and once se-cretly inscribed, it rose to new heights of Arensberg-like occult significance. Another blatant example of an interest in that literally secret writing and enciphering that was equally shared by Arensberg and Duchamp is the art object called À bruit secret Read More:http://www.scribd.com/doc/46327185/Alchemist-of-the-Avantguard

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Thanks for quoting my Doctoral dissertation, apropos Duchamp’s cccult credentials.

Regards

Glyn Thompson.

A+