The why of Bertolt Brecht’s popularity in America has always been a bit complicated. One way or another, the United States held a personal fascination for Brecht, and his attitude towards it developed through two distinct phases. As a young man he liked to portray America as the cockpit of capitalistic barbarism; later when he had fled from Nazi Germany and settled in Santa Monica between 1941-48 he stopped writing about America and tried to come to personal terms with it.

---Brecht and emotion are often said to be sworn enemies. His epic theater was designed in opposition to the sappiness of conventional drama. Audiences are meant to think, not weep. But if Brecht were as boringly theoretical as he’s sometimes made out to be in university seminars, his work would have long faded from the repertory. A consummate man of theater, he employed all the tools of his trade (story, character and, yes, even heart) to provoke, challenge and entertain. And Doyle, working in the stylishly resourceful way in which he has re-imagined how Stephen Sondheim musicals can be staged, brings enormous inventiveness to an undertaking that few regional theaters in America would have the intellectual passion, never mind the guts, to pull off.---Read More:http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2010/02/theater-review-the-caucasian-chalk-circle-at-act.html

Early and late, Brecht was somewhat misguided. He failed in both attempts and for the same reason: he was too profoundly German. When he thought he was writing about the U.S. , he really was projecting his vision of the worst in German society. When later, he tried to impress American motion picture producers or theatre audiences, more often than not he resorted to ferocious stage ideas or a style that could not be transplanted from the Berlin of the twenties to a totally different context.

---Walter Benjamin, though associated with Marxism and Surrealism, adopted various positions at first, most of them subtle, not to say ambiguous. Art, he thought, occupied a fragile place between a regression to a mythic nature and an election to moral grace. After his reading of Lukács and meeting with Brecht, he saw art as a montage of images specifically created for reproducibility. Stripped of mystique and ritual awe, the artist had now to avoid exploitation by revolutionizing the forces of production. Technique was the answer. Innovations arise in response to the asocial and fragmented conditions of urban existence, and mass communications should be harnessed to politicize aesthetics.--- Read More:http://www.textetc.com/theory/marxist-views.html

…As Brecht’s political attitude took shape, so did his style. The rhetoric of his earliest plays, with their heroes heaving and sighing over the loneliness of the individual spirit, gave way to a new stage language that was terse, ironic, specific, and brutal. Borrowing from Antonin Artaud, he learned to set coarse ideas in gutturals, so that the sounds of the words underscored their meanings, broadening the language of sonority. By the late 1920′s the problems of external discipline and the submission of the individual to authority began to preoccupy the work; plays intending to inculcate Communist ideas into both actors and audience, which sometimes meant intellectual intentions working at cross purposes with imaginative sympathies. It was a tinkering with a new form, “epic theater” to which he built into it everything he thought he could use, from the mechanical steel cage of his early collaborator Erwin Piscator to the pantomine timing of Charlie Chaplin. And it worked.

---Thus, even if the pacifist dream was realised, bourgeois violence would go on. But in fact it would not be realised. How could a bourgeois coercive State submit to having its source of profits violently taken away by another bourgeois State, and not use all the sources of violence at its disposal to stop it? Would it not rather disrupt the whole internal fabric of its State than permit such a thing? Is bourgeoisdom not now disrupting violently the whole fabric of society, rather than forgo its private profits and give up the system of economy on which it is based? Fascism and Nazism, bloodily treading the road to bankruptcy, are evidence of this. Bourgeois economy, because it is unplanned, will cut its own throat rather than reform, and pacifism is only the expression of this last-ditch stand of bourgeois culture, which will at the best rather do nothing than do the thing that will end the social relations on which it is based.--- Read More:http://www.marxists.org/archive/caudwell/1935/pacifism-violence.htm

Epic theater’s basic acting tone and rational calm seem to have been prompted by rebellion and, in particular, rebellion against caste presumption. Anyone who has listened to old reels of German officials or orators, expecially Nazi orators, are likely to be struck by the outraged tone, the bellow of the superior, the screech of the martinet, which pervades the speech. Certain critical words seem to fascinate, terrorize, and arouse German audiences, to prepare them for the kinetic words of release: soil, our folk, iron, might, fight our way out; all means of which the populace can be provoked to mindless violence and then left so emotionally depleted as to be incapable of resisting new commands.

This process of emotional depletion also occurs in the drama as defined by Aristotle: the spectator is drawn into the tragic dilemma of the actor; he comes to accept the actor’s situation and at first feels pity at the actor’s plight, and then terror- as he begins to identify his own personality with the one presented by the actor. Ultimately, as the drama reaches its excruciating resolution, the spectator experiences a total empathy and leaves the theater purged by the catharsis of his experience. And this “cleaning out” of all the spectator’s stale slag of feeling was, Aristotle maintained, socially good. Brecht said it was socially bad.

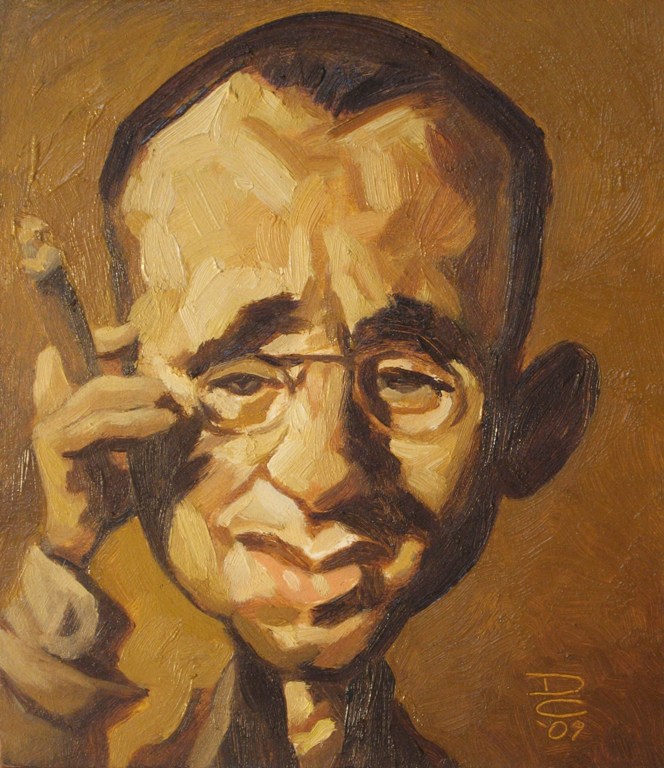

---Don Coker art. ---Caudwell:Thus it is beside the point to ask the pacifist whether he would have defended Greece from the Persian or his sister from a would-be ravisher. Modern society imposes a different and more concrete issue. Under which banner of violence will he impose himself? The violence of bourgeois relations, or the violence not only to resist them but to end them? Bourgeois social relations are revealing, more and more insistently, the violence of exploitation and dispossession on which they are founded; more and more they harrow man with brutality and oppression. By abstaining from action the pacifist enrolls himself under this banner, the banner of things as they are and getting worse, the banner of the increasing violence and coercion exerted by the haves on the have-nots. He calls increasingly into being the violences of poverty, deprivation, artificial slumps, artistic and scientific decay, fascism, and war. Read More:http://www.marxists.org/archive/caudwell/1935/pacifism-violence.htm image:http://www.doncokerart.com/blog/?p=117

It is not very hard, given Brecht’s experiences and personality, to see why. If Aristotlean drama burned an audience’s social feelings away, the practical effect of this drama would be detrimental. What society in general, and the Communist movement in particular, would have to develop, was a theory and practice of the theater which would describe the conditions of life of a whole group of people, not of an individual. To do this, the dramatist must insure that no performer becomes the conduit of the spectator’s empathy:

Brecht wrongly equated empathy, without which no audience will be interested in the stage action, with illusi

which is not at all necessary and comparatively novel, being a feature of naturalistic drama. For feelings that overwhelm the audience Brecht wished to substitute reason. Because naturalistic theatre aroused excessive emotion and ignored reason Brecht supposed these two, reason and empathy, to be mutually exclusive. Yet in Greek tragedy or the plays of Shakespeare both are active. The problem is not empathy as such, but the degree and kind of empathy aroused.

As a playwright Brecht’s sense of what works led to the writing of scenes where the audience’s empathy for the characters on stage is considerable: the heroic self-sacrifice of the dumb Kattrin in Mother Courage is a notorious instance. Martin Esslin points out the psychological flaw in Brecht’s reasoning:

“Without identification and empathy, each person would be irrevocably imprisoned within himself.”

Esslin duly points out that his use of the V-effekt shows how conscious Brecht was of the audience’s tendency to identification. He did not eliminate it, but modified and weakened it. Esslin suggests that this is the particular genius of Brecht’s theatre, the partial failure of Verfremdung: this creates a tension between the author’s intention and our tendency to identification. We are at the same time able to feel sympathy for a character, while our reason leads us to condemn him or her roundly. In his theoretical attack upon romanticism and emotion Brecht claims to be the advocate of reason. Yet in his writing of plays, Brecht time and again creates scenes that move the audience, in spite of the distancing devices.

Because he seems genuinely to believe that his work is free of strong emotion, Brecht makes no effort to suppress or conceal this element. And because our sympathy is continually rebuffed, when emotion manages to take hold of the audience, it may be all the stronger for that. Read More:http://www.teachit.co.uk/armoore/drama/brecht.htm

ADDENDUM:

After all, his popularity has depended on fertile misreading since 1928, when the ruthless send-up of Weimar cabaret songs that was “The Ballad of Mack the Knife” leapt off the stage of the Schiffbauerdamm theatre in Berlin to become one of the most-recorded standards in the history of pop music. Brecht (and his then composer Kurt Weill) might have hankered for an art that hastens the overthrow of capitalism; instead, they got covers from Bobby Darin, Frank Sinatra and every lesser lounge-bar crooner. In any case, many taut and questing poems by this supreme praiser of doubt stress that art, and thought, must always measure up to an ever-changing reality. ” I advise you to greet/ Cheerfully and with respect the man/ Who tests your word like a bad penny” – even if that word comes from the theoretical works of Bertolt Brecht.

So no one wants Brecht as a model or a monument. “Unhappy the land that has no heroes,” laments Galileo’s assistant, Andrea Sarti, after the heretical astronomer has recanted to the Inquisition. “Unhappy the land that has a need for heroes,” corrects the crushed but ever-alert Galileo. We tend to agree. Besides, the demise of Communism in Europe triggered a predictable bout of character assasination. It aimed to show Brecht as a fallen idol not so much with feet of clay as with actual cloven hoofs. In the 1990s, intellectual parricides such as John Fuegi – once a pillar of the International Brecht Society – attacked not just a * * self-serving Stalinist hack but a treacherous parasite who allegedly stole first the hearts, then the work and even the lives of his collaborators, Elisabeth Hauptmann, Margarete Steffin and Ruth Berlau. Hauptmann, by the way, was still eagerly tending the Brecht flame decades after her supposed exploiter’s death.Read More:http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/theatre-dance/features/bertolt-brecht-was-it-all-an-act-406006.html

COMMENTS

COMMENTS