Jean Genet:”A man must dream a long time in order to act with grandeur, and dreaming is nursed in darkness”

Genet’s stage is a space where politics and metaphysics collide, and partly fuse.Some of it sticks to the wall. Like the theater of Antonin Artaud,Genet’s version combines two seemingly intractable opposites: the sacred and the political.It partly resolved a suggestive form of abstraction within an attempt to re-articulate the individual in modern terms, by searching for possible options to the exclusion of madness, or insanity as a plea of last resort.Still, the belief was that the modern, self-tortured person could articulate his mentality and situation.

With Genet, there was this authority in a willful and determined commitment to being a thief in counterpoint to a somnolent life of bourgeois self-satisfaction. Opposing impulses both attracting and repulsing simultaneously.Finally, some theorists have taught me to not connect work and life too much:But with Genet,any final, definitive truth remains veiled, obscurely hidden, and almost always a secret. Instead of one structured, linear and straightforward narrative one is left with unpredictable surprises, multiple fragments, about minor,and forsaken miracles that is only Jean Genet.

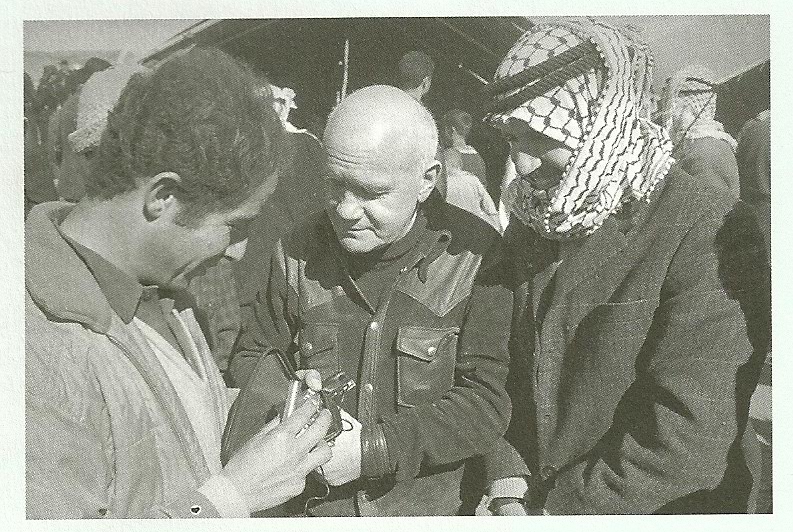

---One of the iconic photos of the 20th Century Allen Ginsberg with Jean Genet in Grant Park, Chicago, 1968. (no photo credit available) Read More:http://contestedterrain.blogspot.com/2011/04/allen-ginsberg-died-april-5-1997.html

…My work as writer is mere pleonasm. It passes the time as I pursue the rehabilitation of the purulent, the dark thrills of the interdit. I left Nazi Germany because it no longer interested me; there, stealing did not differentiate me from authority. Where was the liberation in that? My aesthetics of crime were self-creation and I went back to shack up with Stilitano. Carrying packages of opium for him gave me a sense of CAPITAL LETTERS, MY SUBSERVIENCE A PURPOSE.

This is the life I lived and these are the people with whom I was preoccupied between 1931 and 1942. Bof! But I can sense your erection fading. So let me tell you more about the pleasure of treachery, how I bit Lucien until he bled while he opened up like an anemone, how I sucked off Bernardini, the head of the Marseilles secret police. Was I guilty? Who knows? I just became that of which I was accused ( Genet, Thief’s Journal )…

---Genet’s activism went far beyond the usual demands of fellow travelling. Leonard Bernstein may have thrown the odd cocktail party in honour of the Black Panthers, but Genet, who had done time for theft in his youth, toured the US for weeks, making speeches on behalf of the organisation’s imprisoned leader, Bobby Seale. Ultimately, he wrote a manifesto in which he proclaimed that “to help save the blacks, I am calling for crime, for the assassination of whites”. Among the more surprising signatories to this incendiary epistle was Jacques Derrida, who supervised Laroche’s doctoral thesis, which formed the basis for The Last Genet , originally published in French in 1997.--- Read More:http://www.thenewsignificance.com/2011/04/20/how-jean-genet-literary-genius-lost-the-plot/

In The Blacks Genet had written one of the few plays where the purpose was to insult and confuse the audience. What happens on stage can never be made entirely clear down to its fine detail, but there is no doubt about what happens to the audience: it is humiliated. It is the work for an all-black cast to be played for a white audience. At the very start, hostility is established; not because Genet prefers black society, but because white society is the group in power.

The cast’s faces are partially covered by white masks that represent a queen, a missionary, a governor, a judge and a poet-lackey. Thus, the white audience faces the patently false embodiments of its institutions across a stag peopled by Blacks.

…Voilà. Vous are encore dur. What more can I say? This book is my ascesis. I wanted to rob cripples and queers, I wanted to reclaim the joy of tragedy. But most of all I wanted to glorify myself. Being a thief is banal but writing about it is magnificent and with this exhibitionist act of tedious subversion, I have recreated myself once more as gullible, European radicals reclaim me for their own. ( Genet, Thief’s Journal )

---But he produced nothing more inflammatory than The Blacks. Written in 1958 - and now in a new hip-hop, slam-poetry remix at the Theatre Royal in London's Stratford East - the play sees a company of black actors donning white makeup in order to confront our most deep-seated racial prejudices. Its publicity, for instance, features the black actor and comedian Tameka Empson made up in white facepaint to look like the Queen. Inspired by a documentary about African religious rituals in which the summoned spi

morphed into the western colonial powers, Genet's play - subtitled "A Clown Show" - is itself a ritual. In it, the murder of a white woman is re-enacted by black actors for the entertainment of an audience of white establishment figures - the Queen, a high-court judge, a bishop - themselves played by the whited-up black actors .--- Read More:http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/oct/17/race.uk

ADDENDUM:

This is what Hadrien Laroche, recently appointed cultural and scientific counsellor at the French embassy in Dublin, calls “the last Genet”, noting in his introduction that “the last also signifies the lowest, the way we speak of the lowest of the low”. For Genet’s political passion in these years focused on three rather questionable causes: the Black Panther Party, Germany’s Red Army Faction and the Palestinians’ guerrilla struggle against Israel. Over the course of The Last Genet Laroche gradually unfolds the sometimes sinister implications of the author’s involvement in these movements, which seems to have derived from a combination of their aesthetic appeal, drugs, sexual desire and genuine indignation, but also from some unresolved prejudices of his own…

---In numerous articles and interviews from the 1950s onwards, Genet isconsistent in his claims that political drama that attempts to educate its audience either through mimesis or defamiliarization betrays ‘the virtues unique to theatre’, which, as he claims in ‘That Strange Word …’, have to do ‘with myth’. Genet continues:Politics, history, classical demonstrations … will have to give way tosomething more … sparkling. All that shit, that manure will be elim-inated … If, despite ourselves, they slip into the theatrical act, theyshould be chased out until all traces are erased: they are the dross thatshould be used to make movies, TV, cartoons, romans-photo . --- Read More:http://www.scribd.com/doc/48544854/jean-genet-performance-and-politics image:http://pepisymposium.blogspot.com/2010/10/jean-genet.html

…Genet’s commitment to the Palestinians was even more emphatic, and he spent months at a time living in their refugee camps. After the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982 he was on hand to witness the aftermath of the Shatila massacre, recording the carnage with grim precision: “The first corpse I saw was that of a 50- or 60-year-old man. He would have had a ring of white hair if a wound (an axe blow, it seemed to me) had not split open his skull. Part of the blackened brain was on the ground next to this head. The entire body lay in a sea of black, clotted blood”.

Genet clearly deserves credit for drawing attention to the plight of the Palestinians at a time when broad sympathy for their cause was more limited than it is today, but, as Laroche reveals, some of his writings on the subject carried unmistakably anti-Semitic overtones. He also dredges up some passages from one of Genet’s early novels that express a perverse admiration for Hitler, who is described as a poet. In all this Laroche can be commended for scrupulously outlining the political context of “the last Genet” without letting him off the hook. Read More:http://www.thenewsignificance.com/2011/04/20/how-jean-genet-literary-genius-lost-the-plot/

——————————-

---Time Magazine (1963): In an age increasingly forced to distinguish between scatology, pornography and the legitimate study of evil, the story of Genet's progress to literary prominence exerts a monstrous fascination. For Genet is a matchless, unholy trinity of all three. Beside him, Henry Miller is but a cheerfully smutty college sophomore, Sade a dilettant aristocrat of eccentric habits, Gide a genteel old lady sedately cultivating nightshade in her little kitchen garden. Read More:http://criticaltheory-download-ebooks.blogspot.com/2011/05/georges-bataille-on-jean-paul-sartre-on.html image:http://home.earthlink.net/~tshbsg/theater/screens.htm

Yet for all his utopian commitment to poetic revolt, Genet was also apragmatist, a thinker who realized that revolutions are produced withguns and through violence. Thus while some of Genet’s political essaysexpress a distinctly idealist view of global politics, he is disdainful of revolutionaries who merely make ‘empty gestures’ (ibid., p. 37). Genet’sretrospective commentary on the failure of May 1968 is sarcastic aboutthe students who adopted such gestures:In May ’68, the students occupied a theatre, that is, a place from whichpower has been evacuated, where theatricality remains on its own,without danger. If they had occupied the Parisian law courts, first, thatwould have been much more difficult, since that building has moreguards protecting it than the Odéon Theatre, but above all, they wouldhave been obligated to send people to prison, to pronounce judgements; then you’d have the beginning of a revolution. Genet also remained suspicious throughout his career of the claims of committed literature….

---Then Ken Kesey, the acid-tripping author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, showed up stoned to meet Jean Genet. As a woman translator from Ramparts worked overtime to facilitate their conversation, the blissed-out Kesey pointed down to his feet and said: "I'm wearing green socks. Green socks. Can you dig it? Green socks. They're heavy, man, very heavy." The translator, not knowing that "heavy" meant "significant," even "marvellous," translated, Les chausettes vertes, elles sont très, très lourdes, and Genet managed a quizzical, sympathetic smile for these burdensome socks. Next Kesey proposed playing basketball: "There's nothing better than playing basketball with Negroes." David Hilliard announced: "This motherfucker is crazy and we're getting out of here." The bewildered Kesey asked his hosts, "Don't they like basketball? I thought Negroes loved basketball."--- Read More:http://www.ralphmag.org/BB/black-panthers.html

…As he states in the 1960 ‘Avertissement’ to The Balcony, political theatre is dangerously paradoxical:When the problem of a certain disorder or evil has been solved onstage, this shows that it has in fact been abolished, since, according to the dramatic conventions of our times, a theatrical representation can only be the representation of a fact. We can then turn our minds to something else, and allow our hearts to swell with pride, seeing that we took the side of the hero who aimed successfully at finding the solution. For Genet, conventional political theatre too often indulges the spectator by depicting the revolution as having already happened. Instead of encouraging the audience to change the world, it acts as a safety valve,and thus works to support the status quo. As the essays in this collection demonstrate, Genet advocates a different, more radical version of committed theatre as political event rather than mere spectacle. Read More:http://www.scribd.com/doc/48544854/jean-genet-performance-and-politics

COMMENTS

COMMENTS