Is it possible to be so politically correct that we end up chewing our own tail. Is there a realm within the politically correct that is not politically correct? Its been said that as long as there exists the dynamic of sex and aggression, then violence and destruction are potential happenings. If all activity is sealed down, the hatches are battened with the politically correct, how do the excess vapors escape, and secondly, is there a way to express the politically incorrect in a positive way or is that an oxy-moron, a paradox. The politically correct as normative religion? Perhaps, as some have suggested, the only option is within a camp sensibility applied to pop culture, as a means of challenging the accepted norm and reaching in a post-modernist sense towards an elevated principle, one mediated by images within a matrix of sensation. Rebellious unconventionality that manages to result in non-idealized versions of the truth and mutating abstract ideals within the ugly reality that comprises industrial entertainment.

---If kitsch was a pawn, it was also a scapegoat. Beginning in the 1960s, a movement to reclaim the pleasure found in popular arts was espoused by Susan Sontag's "Notes on Camp." The camp "sensibility" offered a mode of appreciating kitsch (as well as "serious" art) because of its excessiveness, its role-playing, its overt decoration. Individuals with camp sensibilities sophisticate the understanding of kitsch, for camp judgments imply a specific way of perceiving--a trained eye or ear that stands parallel to Greenberg's elite coterie of artists and viewers. Throughout the twentieth century, certain artists and critics have offered affirmative accounts of mass culture. European and American modernists, notably Fernand Léger and Stuart Davis, incorporated images of consumer advertisements and packaging into their paintings. Their industrialized abstract visual languages suggested a fundamental accordance between avant-garde art and mechanical production. Walter Benjamin believed that the masses could take advantage of new forms of artistic production made possible by modern technology to transform the existing power structure, using kitsch as a weapon against the self-alienation wrought by fascism.--- Read More:http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/kitsch.htm

The other issue is the disembodiment factor that comes from watching these pop culture shows. The zombie syndrome. Mass media has an infinite capacity to mythify and magnify and the content is in the service of the modalities of the medium. The force of pop culture in its negative aspects is that it plays to our absence to have full immersion, the kind of sensorial engulfing that would be apparent as a live event. So, there is a passive-aggressive nature built into mass media culture and our experiences are divided, sliced and diced like our perceptual field and watching any of these shows seem to have the same generic, pre-determined feel. Very little of Emmanuel Levinas’s idea of the face to face, meaning we never have to deal with the face of the Other. At its bases, mass media serves to conceptualize the totality of our being, and the important aspect, the individual is subservient in status and dignity to being….

---The Modern Word: What is postart and what is the relationship between postart and postmodernism? Donald Kuspit: The concept of “postart” was developed by the happening artist Allan Kaprow. Simply put, it involves the “blurring of the boundary between art and life,” to use the title of his collection of essays. I would add, based on his idea that life is much more interesting than art, at the expense of art. I think postart is the gist of postmodernism, as the view that it involves the blurring of the boundary between avant-garde and kitsch suggests.--- Read More:http://bookofdayspaintings.wordpress.com/the-end-of-art-%E2%80%93-a-book-by-donald-kuspit-emmet-cole-interviews-donald-kuspit/

ADDENDUM:

Milan Kundera and Clement Greenberg write about kitsch that “For none among us is superman enough to escape kitsch completely. No matter how we scorn it, kitsch is an integral part of the human condition” and that “Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations. Kitsch changes according to style, but remains always the same. Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times. Kitsch pretends to demand nothing of its customers except their money” (Greenberg ). At the crossroads of kitsch, between Kundera’s notion of the irresistibly human and Greenberg’s total spuriousness, lies the first serious glimmer of camp. Can we locate, or for that matter begin to define, camp in the arena of contemporary culture? Is this seductive phenomenon a preposterously pretentious expression of kitsch, which belongs to the “artsy” demimonde? Camp, or rather its essence, has been defined as “a love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration … something of a private code, a badge of identity” (Sontag ).

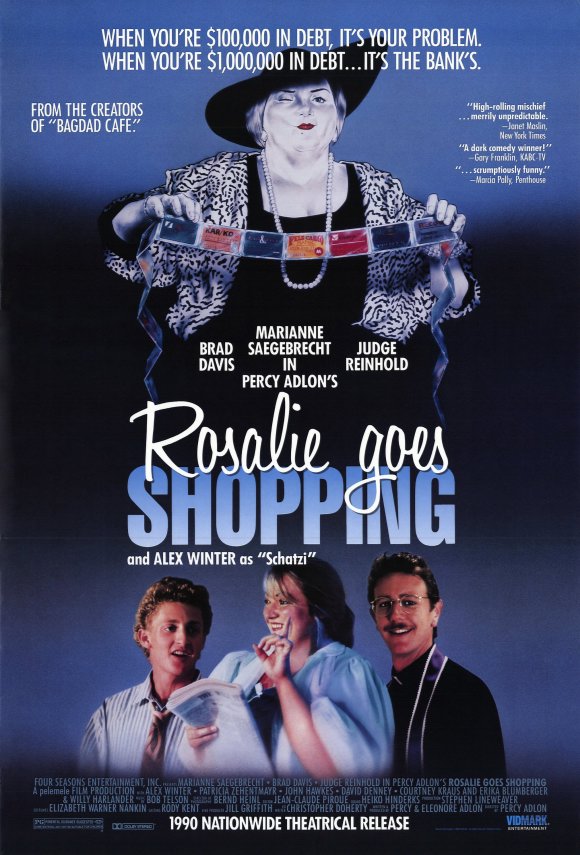

…the phenomenon of camp through the cinematic language of Percy Adlon’s Rosalie Goes Shopping (1989-90) . Rather than approaching the film in its entirety, I discuss three dense sequences which highlight camp sensibility. My understanding and interpretation of this filmic material begs two questions at the heart of the camp phenomenon: How does camp sensibility contribute to contemporary interpretations of art, and what promise of change does it playfully conceal?

Before Rosalie’s seductive sequences, I must put the discourse of camp into perspective, beginning with a modernist fantasy of beauty’s inherent ugliness. Georges Bataille’s notion of a “strange mise-en-scène” or active process of denuding the beautiful object of its illusion of totality, begins to open space for camp possibilities. “Do not all beautiful things run the risk of being reduced to a strange mise-en-scène, destined to make sacrilege more impure? And the disconcerting gesture of the Marquis de Sade, locked up with the madmen, who had the most beautiful roses brought to him only to pluck off their petals and toss them into a ditch filled with liquid manure? In these circumstances, does it not have an overwhelming impact?” (Bataille ).

As Sade’s prison compatriot tears up rose petals and then cavalierly tosses them into a stinking pool of manure, the camp moment disassembles mainstream ideas of beauty. Through dismemberment and disassembling, Bataille’s hero breaks down the oppositional concepts of beauty and ugliness; he ruins their oppositional drama. Bataille juxtaposes the literal object — the referent of the rose in nature — to various poetic “rose inflections” to demonstrate the ambiguity at the heart of beauty; the only resolution of this floral dilemma rests in the ugly interface of the

natural, literal representation and the poetic image, the rose in the “mind of the genius.” Read More:http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1101&context=clcweb&sei-redir=1&referer=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.ca%2Furl%3Fsa%3Dt%26rct%3Dj%26q%3Dpop%2520culture%2520kitsch%26source%3Dweb%26cd%3D2%26ved%3D0CCkQFjAB%26url%3Dhttp%253A%252F%252Fdocs.lib.purdue.edu%252Fcgi%252Fviewcontent.cgi%253Farticle%253D1101%2526context%253Dclcweb%26ei%3DbjLzTqiiFubI0AG64MmCAg%26usg%3DAFQjCNF_3shJTqWPBhvjEXjE4PK1LtRgOg#search=%22pop%20culture%20kitsch%22

…Could it be possible that camp exists in and along other art forms and critical categories? Might the serious exposition of kitsch lead to other considerations? Is contemporary camp sensibility one of the liberating cultural subordinates the way Fredric Jameson proposes? These questions continue to defy straightforward answers. I believe that the ambiguous space of camp and its play with dense frames as well as the mise-en-question of totalized beauty clears the way for an understanding of art as everyday engagement. “I’m going multinational. Just think: Helping people beat the system worldwide”: The prophetic last words of Rosalie best capture the consequences of an everyday tactics read through the sensibilities of camp. We are not left with an image of a megalomaniacal woman spreading the contagion of fraud worldwide. Rather, we are left with the possibility of everyday subversive play. Camp sensibility allows us to reappropriate cultural material, imaginatively opening new spaces for meaning. ( ibid. )

——————————-

One of the key threads in The End of Art is the idea that fear and ignorance of the unconscious have created a climate of creative superficiality within which artists are unwilling to breach the surface meniscus of their minds to the uncomfortable waters that lie beneath. What are they scared of? How did the modernist fascination with the unconscious turn into the postmodern horror of it?

They are scared of the inner truth about themselves, more particularly, about acknowledging psychic conflict and trauma as well as the primary creativity evidenced by fantasy (especially dreams). I think the early modernists – Gauguin, Redon, Max Ernst, de Chirico, etc. – were less scared because the world seemed scarier than the unconscious. Militarism and materialism, authoritarianism and capitalism, were more devastating (Meyer Schapiro documents their bad effect on 19th century artists) than anything in the unconscious, even though they had unconscious roots – another reason to explore the unconscious. As for the postmodern

ection of the unconscious, and the treatment of it as another “discourse,” it was inevitable that one had to withdraw from it, on the principle that if one looks into the abyss the abyss will look into you (Nietzsche). One can look only so long into the depths without becoming dizzy and falling in, which is why the postmodernists prefer not to look deeply but stay on the everyday surface of life….

…In The Anxiety of Influence, Harold Bloom argues that modern poets have an Oedipal relationship with the great poets of the past. In some ways, isn’t postart a valid response to the anxiety that being brought up in the shadow of greatness causes?

Yes, “the anxiety of influence” is also operational in postart, but I would say it is more pre-Oedipal than Oedipal in import, for it involves an attempt to annihilate the art of the past – traditional and modern – through indifference and ignorance. (Many postartists seem to be art school graduates who know next to nothing about the history of art and everything about the youth culture. Postart seems to be a part of it. The muse of Warhol and Hirst seems to be the bitch goddess of popular culture success.) I also happen to think avant-garde art’s relationship to traditional art was pre-Oedipal rather than Oedipal, as Bloom thought it was, with the difference that avant-garde art wants to annihilate traditional art by analizing it out of unconscious envy. (I am referring to Chasseguet-Smirgel’s idea of the “anal universe.”)…Read More:http://bookofdayspaintings.wordpress.com/the-end-of-art-%E2%80%93-a-book-by-donald-kuspit-emmet-cole-interviews-donald-kuspit/

COMMENTS

COMMENTS