Celebrity as a cultural signifier. The need for the sacrificial. Are myths to a large degree, constructions, fabrications, which are conspirational in nature? Something to serve a base need as a substitute for finding meaning in life. Here, the victim is both the cause and the solution of the sacrificial crisis. A projection of our own desires and striving for the eternal, however misguided, and to touch the hem of the garment, a little tactile confirmation of immortality. It sounds kind of kitsch. Kundera’s “second tear”;The first tear rolls down the cheek out of pity; the second tear, the sequel in recognition of our own feeling of pity.The self-congratulatory loop. myth part of an overblown sentimentality from a co-mingling of naive faith with paranoid suspicion….

from an article by Matthew Schneider relating Hugh Schonfield and the Beatles. Shows a great deal about the mechanisms of mass hysteria, anxiety and sacrificial ritual among other even more complex issues, especially when considering Lennon’s intelligence and his near lifelong understanding of the forces, the spaces between perception and reality and relationship between essence and the world at large…

…Phase two ties together and tidies up the loose ends and unaccountable details left behind by Jesus’ own, partially successful, conspiracy, producing, by about the third century, a myth capable in Schonfield’s opinion of instituting a great world religion. But as that myth was reverently scrutinized, accumulating through the years a weighty interpretive tradition, its loose ends continued to turn up and demand explanation. As Christianity spread after about 300 C.E. to an increasingly educated and intellectually sophisticated populace, the need for a stable originary narrative–capable of withstanding the skepticism of friend and foe alike–became more urgent. Schonfield argues that the early church stabilized the myth of Jesus’ life and worked first by obliterating any lingering traces of the Passover Plot, and finally by mining the Old Testament for every possible prophetic detail until the two parts of the Bible, taken together, constituted a seamless cosmological narrative. To Schonfield, though, in the end this is just a story, carefully and tendentiously abstracted from a chaos of events related only by their having occurred in roughly the same region at about the same time. Those events are capable of being woven into a different narrative, and this is precisely what Schonfield did.

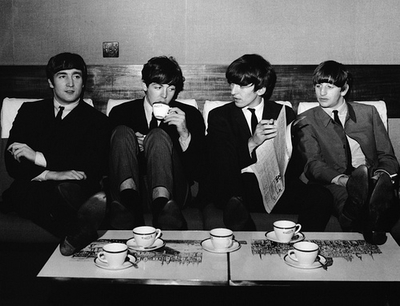

This is what struck Lennon more than anything else in Schonfield’s book. The insights John took from The Passover Plot were more cognitive and historiographic than theological: at no time did Lennon state that he believed Schonfield’s hypothesis in all its particulars. Rather, as the Evening Standard interview suggests, reading the book seems to have impelled Lennon to consider his own fame and the phenomenon of Beatlemania in their broader cultural and historic contexts, and to conclude that the psychic, political, and cultural forces that went into the making of Christianity had been revived by Beatlemania. The world of Jesus’ birth was characterized, in Schonfield’s words, by “an extraordinary fervour and religiosity in which almost every event, political, social, and economic, was seized upon, scrutinized, and analyzed, to discover how and in what way it represented a Sign of the Times and threw light on the approach of the End of The Days. The whole condition of the Jewish people was psychologically abnormal. . . . People were on edge, neurotic. There were hot disputes, rivalries and recriminations” (30). That Beatlemania rose to the level of neuroticism was made apparent by the spectacle of the Beatles being greeted by hundreds of screaming fans at airports around the world. George Harrison has said that in the 1960s, “the world used [the Beatles] as an excuse to go mad, and then blamed us for their madness.” Other experiences no doubt also contributed to Lennon’s sense that the Beatles had aroused another era of psychological abnormality. Ringo Starr has recalled that during their tours, the Beatles frequently found themselves presented with the sick and afflicted:

Crippled people were constantly being brought backstage to be touched by “a Beatle,” and it was very strange. It happened in Britain as well, not only overseas. There were some really bad cases, God help them. There were some poor little children who would be brought in in baskets. And also some really sad Thalidomide kids with little broken bodies and no arms, no legs, and little feet….

…To Lennon, fresh from reading Schonfield’s minute-by-minute account of Holy Week, these events no doubt bore a chilling resemblance to Jersualem’s violent swing from adulation to excoriation of Jesus between Palm Sunday and Good Friday. Perhaps this is why Lennon refused to recant his statements during the U.S. tour, since each day presented further proof that his original intuition–that Beatlemania and Schonfield’s version of Christianity were parallel phenomena–was on target.

There was more to this parallel, however, than just Jesus’ and the Beatles’ shared identity as foci of adoration and scorn. By 1966 the Beatles’ longevity–unprecedented for pop stars at the time–had made them and their music objects of the kind of scrutiny and study previously reserved for venerated religious figures and sacred texts. After reading Schonfield, Lennon realized that the Beatlemaniac’s insatiable thirst for every scrap of information about her idols was functionally identical to the religious acolyte’s hunger for a more comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of the godhead. Both are satisfied only by obsessively poring over every available tidbit, which is tirelessly studied for hidden messages and archetypal significances. Schonfield also showed Lennon that such an understanding was always predicated on a story–that is, a purposeful narrative stitched together from life’s jumble of contingencies. These two realizations, combined with the “bigger than Jesus” controversy and its aftermath, pointed out a new direction for the Beatles, one in which they could broaden their cultural significance by exploiting and amplifying–rather than obscuring or repudiating–their quasi-religious status….

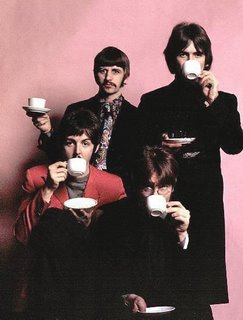

…When the Beatles emerged from their self-imposed hiatus nearly a year after their last concert with a new album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, they were a different group: all four sported new hairstyles, drooping moustaches, and wore vaguely psychedelic parodies of the quasi-military uniforms customarily used by members of northern English community brass bands. Most important, John Lennon proudly wears his National Health-issued round spectacles as a sign of the bookishness that he had, presumably, concealed to protect his image. These iconographic alterations were meant to signal that the Beatles had transformed themselves from history’s most successful purveyors of rock and pop for teenagers into artists–that is,

vers of complex, subtle, and deep narratives about humankind’s enduring questions.But despite these signals and the hoopla that greeted the new album, the music on Sgt. Pepper wasn’t any deeper, more evocative, or more experimental than what the group had been doing for the previous year and a half. The music seemed more meaningful and capable of sustaining a more sophisticated interpretive inquiry, though, because of the care that had been taken with the album’s ancillary features–particularly the sleeve design, which appears carefully composed to communicate a manifestly grand message. But even this aspect of the record is deceptive. Though now frequently identified as pop music’s first “concept” album and a “manifesto of the 1960s,” Sgt. Pepper, by its creators’ admission, was a musical hodgepodge, tied together only by the title song and a brief repeat of that song in the penultimate track. “All my contributions to the album,” said John Lennon, “have absolutely nothing to do with this idea of Sgt. Pepper and his band; but it works, because we said it worked, and that’s how the album appeared. But it was not put together as it sounds, except for Sgt. Pepper introducing Billy Shears, and the so-called reprise. Every other song could have been on any other album.” Lacking real thematic and conceptual unity, Sgt. Pepper nevertheless “works” because its very randomness evokes High Modern obscurantism. As was the case for the conspiratorial view of history Lennon learned from Schonfield, what matters is the system: the appearance of merely accidental or chance relations between elements is, in this way of thinking, the surest indicator of the presence of a hidden story, waiting to be brought to light by the sort of thoroughgoing exegesis practiced on a manifestly important cultural artifacts, like Schonfield’s Dead Sea Scrolls…. Read More:http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0802/beatles2.htm

COMMENTS

COMMENTS