Walter Gropius soon realized that his vision could not be realized by one man alone. What was needed was a laboratory of design in which a new generation of artists could apply the discoveries of modern art to architecture and other needs of daily life. Such a new school would have to select talented young people, before they had surrendered to the conformity of the industrial community or had withdrawn into ivory towers, and train them to bridge the gap between the rigid thinking of the business type and the imagination of the creative artist.

---But here’s what the Republicans and even some moderate voices are missing: this campaign poster isn’t evidence of a “messiah” complex; it pays homage to a pivotal era in graphic design history: the German Bauhaus movement during the early 20th century . As I’ve noted elsewhere, Obama’s design team is very, very good — they would know the history of German graphic design. Obama’s Berlin poster contains the same bold, diagonal lines and sanserif type which typifies 1920s -era German “industrial design.” ---Read More:http://meaningfuldistractions.wordpress.com/2008/07/23/md-exclusive-obamas-berlin-flyer-not-messianic-pays-tribute-to-german-design/

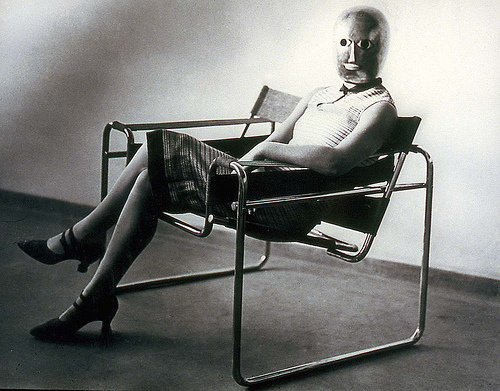

…Ludwig von Bertalanffy, the developer of General System Theory, argued that the modern “crisis” was caused by the conflict between an open system organic model of human behavior and a closed system robot model of human behavior — and by implication the lifeworld — and in the Bauhaus the robot system has won the battle, at least on the battlefield of art. But technology was well on its way to conquering the lifeworld before it conquered art, suggesting that the Bauhaus was fitting art into technology rather than using technology to make art. The Bauhaus described itself as a “unity” of “art and technology,” but I would say it confirmed technology’s triumph over art rather than art’s triumphant appropriation of technology. The Bauhaus endorsed and adapted to technology, not vice versa. …

---In short, the Bauhaus pursuit of purity in art is peculiarly similar to the Nazi pursuit of purity in society. Both pursued technological purity for its own sake, imposing it on rather than integrating it into everyday life. For the Bauhaus, Expressionist and Surrealist art were the "impure" art of Untermenschen (social misfits, at the least, that is, those who "by nature" cannot fit into society, who are flaws in its imagined perfection). In contrast pure Bauhaus art was the art of robotic Übermenschen, that is, machine-perfected human beings--- Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/bauhaus-war-machine12-2-09.asp

There is no doubt that once the Bauhaus moved to Dessau from Weimar it began to receive a considerable income from the sale of designs for industrial mass production. The students worked for short periods in factories to study methods and processes that preceded design rather than being mere stylists. It can be asserted that they were thoughtful and mostly practical attempts to bring technical and functional requirements into harmony with aesthetics, the “smartly modern” but its clear that the artistic endeavor was subsumed by commercial and industrial considerations.

…Let’s be even more farfetched: I suggest that Bauhaus works of art have a drone-like quality, that is, they are oddly like the unmanned drones beginning to be widely used in contemporary warfare. They anticipate and prophesize the future, as art has been said to do, making them “futuristic” — indeed, in Marinetti’s sense, for they are the ultimate instruments of the war of the new against the old that he celebrated (along with war in general as a cleansing purge, which is what, it so happens, Marcel Duchamp thought Dadaism was; is there a Dadaist nihilistic undertone — a purge of “ethnic” or “native” art — in Bauhaus art?). Bauhaus drones are made in art factories — haven’t art schools become art factories these days, and also places where art is mass-produced, however “customized” to suit “individual” tastes — and seem self-propelling. It is as though no artist made them, even if an artist “controls” them from an “abstract” distance….

---For example, art historian Frederic J. Schwartz's essay, “Utopia for Sale: The Bauhaus and Weimar Germany's Consumer Culture,” discusses the impact of publicity on Bauhaus style. Analyzing the unsuccessful reception of the Bauhaus on Weimar Germany's market, Schwartz contends that Bauhaus leaders grew uncomfortable with the market's ability to refashion utopian ideals into mere selling points. While the Bauhaus focused on assembly line productions as an aesthetic model, its spare design never successfully separated itself from the debate between type and originality, becoming notable for its fad-like “industrial style” and fitting neatly within the commercial culture it was attempting to transform. --- Read More:http://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/Reviews/guest-jelley_review.htm

Its ironic that the Bauhaus has been lauded, iconized, as the gold standard for the democratic values of modernism. Criticized by the Nazis for degenerate, cultural bolchevism only to end up serving industry. Bauhaus was non-ideological in Gropius’s conception, yet its members were complicit in building Germany’s wartime military industrial complex including the design of concentration camps as a realization of Gropius’s ethos to ” bring beauty and unity into the chaos of our time.” Obviously overlooked in promoting Bauhaus as a symbol of social progress.

Certainly, this new vision of utopia was predicated on the school’s increasing technological focus, where the dominance of materials eventually transpired at the level of form and into the fetish object as diverse as Apple products to Audi’s. Post WWII it was peddled as anti-fascist artistic freedom, a bulwark that would hold the tension between art and commerce, yet the inherent austerity, the minimalism, could really only serve commercial/industrial requirements.

…They’re precise enough to hit a target audience and do physical and emotional damage in the lifeworld — reduce it to its “bare” essentials, which turns it into an inhuman wasteland (look at the Bauhaus malls, industrial parks, rows of skyscrapers along Sixth Avenue, all barbarically anonymous). Deadpan Minimalism is its degraded ancestor — even as boxy International Style skyscrapers, with their grid construction, signal the triumphant conventionalization of Bauhaus, and with that its trivialization into a formula — and the sterile grid its tedious emblem. Rudolf Arnheim regarded the homogeneity of the grid — a vacuous geometry constructed of uniform modules marching with dumb efficiency to purposeless infinity, droning away with military precision in a vacuum of meaning — as the modern emblem of entropy. However superficially heterogenized, the Bauhaus grid remains entropically inert and boring. Bauhaus art is entropic, like war, and like war a calculated dead-end, but its destructive power — the violence it does art — is hidden by efficiency, while real war is openly violent and messy. The Bauhaus is the end of art as a humanizing activity, and the beginning of technology as entertainment. Max Ernst’s monstrous Celebes (1921), a Surrealist war machine, speaks more directly to modern barbarism. Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/bauhaus-war-machine12-2-09.aspa

---In 1981 Jobs started to attend the annual design conference in Aspen, Colorado. This year the focus was on Italian design and participating profiles were the architect and designer Mario Bellini, the film director Bernardo Bertolucci and the Fiat inheritress Susanna Agnelli. In Aspen, Steve Jobs met the Bauhaus movement's minimalistic and functional design philosophy perpetuated by the architect Herbert Bayer, and seen everywhere on the Aspen Institute area. Like his mentors Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, Bayers believed that one can not make a distinction between high art and applied industrial design. Today we all know the expressions "God dwells in the details" and "less is more", said by Gropius and Mies. In a speach at the very same conference two years later, in 1983, Jobs predicted that the Sony style (heavy grey and black high tech look) was on a downward trend. As an alternativ he proposed that new design should take Bauhaus as its starting point and relate more to the functionality and true character. "What we intend to d

to allow products to be high tech, and then package them clean and pare them down so that it shows that they are too. We intend to make them as small as possible, and then you can make them attractive and white just like Braun are doing with their devices'.--- Read More:http://www.deconet.com/blog/home/entry/steve_jobs_and_bauhaus image:http://ffffound.com/image/3b956f24e9138c3ba35b8c1a9777870bc7b95ccb

ADDENDUM:

The Nazi military was an efficient killing machine, and so was the Bauhaus — it ruthlessly killed off its artistic enemies — because it was technically superior to other art, however simple and routine its technology seems today. Just as the Bauhaus thought the history of art climaxed in and ended with their utopian mechanical art and abstract design credo, so the Nazis thought history would be over when they conquered Europe — the world — and imposed their utopia and purist ideology on it. Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/bauhaus-war-machine12-2-09.aspa

----"The hand-and 45 triangle image seems to me to be an artful genesis of the typo-photo ( typophoto ) style pioneered and advocated by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus, which we all know ended due to the oppression of the Nazis. I don't care for the corporate message, but the design seems clearly derivative of Laszlo's typo-photo style and its possible the art was done by one of his students left behind. Not everyone could just pick up and go. " Read More:http://observatory.designobserver.com/entry.html?entry=24358

COMMENTS

COMMENTS