The assimilation of art into cold, hard cash, ripping out its character, heart and guts and exploiting the aura of glamour around it. Its high end commercial art. prostitution. Such a gloomy world when the individual is a commodity. People as things. We get the art we deserve, and if the aesthetic is confined to a mental function where isolated conception trumps the actual work, it will continue to get produces as long as buyers keep lining up for it. When commerce and the superficial diversion of entertainment, pacification, have nearly devoured what was one known as the higher arts….

---Photographs of Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie’s twins—images with a shelf life of less than a week—sold to a transatlantic consortium of People and Hello magazines for fourteen million the next year. The first blush of Knox and Vivienne were worth more than a midsize Lear Jet, more than a goodish penthouse apartment in Dubai, more than 1.4 million malaria nets. It may seem ridiculous, but we value these artifacts so highly for a reason: they belong to the spirits that guide us through the stages of modern life.--- Read More:http://www.laphamsquarterly.org/essays/consumer-products.php?page=all

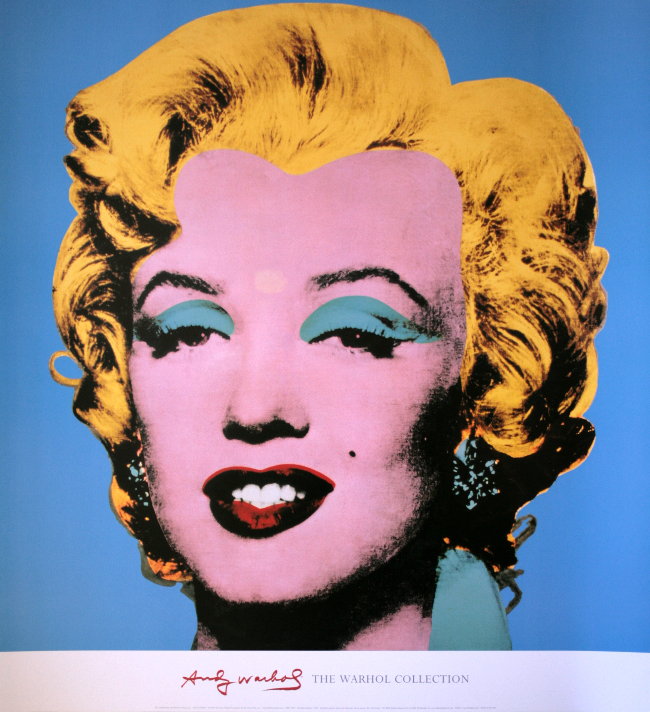

The irony of Pop art, which is inherently anti-subjective, seems to reinforce American materialism. For Pop art was largely a play on commercial images, especially those that represented people as commodities — and commodities (Coca Cola bottles, Campbell soup cans, Brillo boxes) as personages — stereotyping them into a consumer culture spectacle. Andy Warhol’s work is the case par excellence. Its irony amounts to an endorsement of the consumer culture it seems to criticize. It may be a hollow construction, as Warhol’s images suggest, but there is no alternative to hollowness. Its demonstration — the hollowing out of all appearances, indicating that they are socially manufactured myths, valueless in themselves, rather than refining them to suggest that there is something real and humanly valuable within and behind them — became the be-all and end-all of Warhol’s cynical art. There seems to a critical consciousness in this, but the relentless harping on hollowness suggests the unconscious terror of annihilation through the social process that Horkheimer spoke of.Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit2-17-06.asp

Andy Warhol is this epitomy of nihilism, a child of Duchamp. Warhol’s brilliance was the moment he grasped how he could cynically manipulate the market in the artistic sense. The market could be used to exploit art in a mass culture that was increasingly taking its cues from advertising which had permeated the cultural dialog. Warhol was a branch of the industrial entertainment complex. Who knows. Maybe the Valerie Salonis shooting was a staging that got out of hand. It is Walter Benjamin’s nightmare of mechanical reproduction. Rather than emancipating through wider dissemination it was a kitsch machine , assembly line made, dull and catering to a certain death drive.

---Muhammad Ali, 1977-79 Stolen from the Richard L. Weisman Collection, September 3, 2009 "Image courtesy LAPD Art Theft Detail; used with permission"--- Read More:http://arthistory.about.com/od/lost_and_found/ig/weisman_warhol_theft/athlete_series_01.htm

Warhol’s own dramatically superficial self-portraits say it all: There is no self behind his appearance, he stated, suggesting that he realized he was a hollow man. Like empirical-materialistic abstract painting, Warhol’s self-negating work exalts “the collectivity over the person,” to use Horkheimer’s words, rather than the person over the collectivity, as both Dadaism and abstraction once did.Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit2-17-06.asp

So, ultimately, what Warhol confirmed was that celebrities, stars, dead or alive form the basis for our communal lives. The mainstream. Fewer minds wind down the more challenging alleyways. Warhol and Duchamp style pop culture is the central way we understand the world. There is a brilliance in Duchamp, but it is not artistic. It was conceived as something transitional that found points of entry within the eternal and universal of romanticism that fell on its sword in WWI. Should we care, show interest in comprehending ourselves and the society to which we belong, and understanding of celebrities, based on the Warhol template, is our central communal experience gluing together our theories of loneliness and liberty.

---Ours is a business culture not a religious culture, and it is impossible to find spiritual significance in what Warhol called business art. I submit to you that Warhol's art is a celebration of business, which is in part why it sells. It is certainly a long way from the color mysticism of the interiors of the churches that Kandinsky visited and that his early abstract works struggled to emulate. Corporate headquarters are not churches, even though their decoration with works of art are attempts to give them spiritual significance. Warhol's Gold Marilyn Monroe, which I showed you before, 1962, is also irreconcilable with Kasimir Malevich's abstract icons, which he compared to spiritual experiences in a desert, the proverbial place to have them.--- Read More:http://www.blackbird.vcu.edu/v2n1/gallery/kuspit_d/reconsidering_text.htm

ADDENDUM:

In contrast, Warhol’s work epitomizes the business materialism of the crowd, it’s what I call crowd art. Ironically, Warhol’s cynical attempt to turn the dead actress into a sacred presence—and she was very good business, like Elvis—reinforces her profaneness and spiritual insignificance. Gold is either filthy lucre, or, alchemically speaking, ultima materia, that is, the ultimate sacred substance, and Warhol’s perverse fusion—and perversion is another major strategy in art, and irony is part of it in contemporary art—perverse fusion of its opposed meanings in the socio-cosmetic construction of Marilyn Monroe is the ultimate materialistic nihilism. It is the exemplary case of the confusion of values that occurs in a business society, and that Kandinsky fought against….

---The real individuals of our time are the martyrs who have gone through infernos of suffering and degradation in their resistance to conquest and oppression, not the inflated personalities of popular culture, the conventional dignitaries. These unsung heroes consciously exposed their existence as individuals to the terroristic annihilation that others undergo unconsciously through the social process. The anonymous martyrs of the concentration camps are the symbols of the humanity that is striving to be born. The task of philosophy is to translate what they have done into language that will be heard, even though their finite voices have been silenced by tyranny. Max Horkheimer - Eclipse of Reason--- Read More:http:/

.aminonline.com/blog/ image:http://borislurieart.org/The_Boris_Lurie_Art_Foundation.html…What I am arguing is that the spiritual crisis of the contemporary artist is greater than Kandinsky’s. Kandinsky knew art was in spiritual crisis, whereas today’s materialistic artist doesn’t see any spiritual crisis. All that matters is materialistic success.Read More:http://www.blackbird.vcu.edu/v2n1/gallery/kuspit_d/reconsidering_text.htm

————————————–

In spite of recounting at length her zealotry for “trash” and “kitsch,” which she famously claimed to prefer over serious minded films, Seligman never calls Kael to task for disingenuously backing away from her clarion call of the 1960s. “When we championed trash culture,” he quotes her as saying decades later, “we had no idea it would become the only culture.” Seligman doesn’t challenge her myopia. What, for example, did she imagine would be the logical outcome?

As late as 1988, Kael derided Woody Allen’s film Another Woman, in which a philosophy professor (played by Gena Rowlands) finds solace from her malaise, at least in part, through the verses of Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” In her review, Kael raged, “How can you embrace life and leave out all the good vulgar trashiness?” Never mind that by 1988, “vulgar trashiness,” as she calls it, had usurped so much of society that the simple act of reading Rilke (or any poet) might be viewed as reverse escapism, a necessary flight for preserving soul and mind from Kael’s cherished vulgarity. Read More:http://januarymagazine.com/biography/sontagkael.html

———————————

Still, Debord had faith in the moment of revolutionary interruption to reveal the reverse image of the society of the spectacle, at least for a moment. A society in which the products of people’s actions are not divorced from them. A society where to act is to be free and to be free is to act.

The ‘velvet revolution’ in Czechoslovakia was a sublime example of a Debordian moment. His writings still have far more to say to us about the great upheavals in Eastern Europe and China of 1989 than any number of ‘moderate’ chest-beaters.

The Situationist International that Debord led was the last of the avant garde movements of the modern era that combined a revolutionary rhetoric in politics and art. Art that has become a thing apart from everyday life was a lifeless parody of itself to the Situationists. This movement was so uncompromising in its demands on its adherents that one by one all its members were expelled. I like to believe that in the end Debord even expelled himself. Situationist art at its best was a provocation that worked by taking icons and styles from the flotsam of pop culture and turning it against itself. The postmodern art moves and music styles, of appropriating pop images, collaging and cutting them up, are all tame versions of the art the Situationists took to the streets in the heady days of Paris in May, 1968.

“There is nothing they won’t do to raise the standard of boredom” was a famous Situationist slogan of the day. Debord can be credited with reintroducing the notion of boredom to critical thinking about contemporary culture. Drawing on Baudelaire and Schopenhauer, Debord saw boredom as the state that inevitably results once the necessities of food and shelter have been resolved in industrial society. In this he was fundamentally a pessimist. Read More:http://www.toysatellite.org/doods/txt/debord.htm

COMMENTS

COMMENTS