The first impression is of some weekend painter with a crude, vulgar, unskilled hand depicting mercenary goons, violence, power, subjugation, and a whole stock of themes from the politically correct almanac. Once that prejudice falls away there is something quite fatalistic; a society that is pathologically unable to advance; a brutal revelation that human anxiety and trauma may be a complex response to the fear of annihilation and to avoid it, to flee, we adopt a fashionable indifference to horror, and persistently procrastinate in confronting our own uncomfortable truths pacifying ourselves in the sugary pop of kitsch culture, a path which still leads to the nihilistic conclusion. This work is not clever, ironic, decorative or pleasing. But it is honest.

In Golub’s Napalm Flag which Golub painted during the the Vietnam War, the flag is blood-smeared, burned and scratched. Birth or destruction? It does recall a more famous Stars and Stripes, the Jasper Johns Flag. They reflect the bi-polarity of America: hot, intense, and earnest and the other cool, ironic, reflective. Two different ways of perceiving two different Americas. Johns represents an angry yet indifferent as opposed to an angry engagement. You could characterize Johns as a systematic approach to calculated rage; conformist cynical absurdity, mannered fatalism and off hand eroticism jutting up against Golub’s truly dissident and authentic where art is a question of life and death, part of a profound conflict between the wish for eternal life and a spitting in the face of the redemptive covenant.

---In the 1970s, despairing over the fate of his art and his country, Leon Golub destroyed all of his paintings, wiping the slate clean. Born January 23, 1922, Golub underwent a second birth in that act, freeing himself to protest and document what he saw as the crimes against humanity committed by the United States of America. His Napalm Flag (above, from 1974) drenches the American flag metaphorically in the napalm used so mercilessly by the U.S. military in the Vietnam War. As Philip Guston targeted Richard Nixon through his art, Golub aimed more widely, targeting the whole dehumanizing process of war sanitized by the ideology of flags and nationality. From his great moment of doubt, Golub discovered a sense of purpose that would populate his art, sadly, for the next thirty years.--- Read More:http://artblogbybob.blogspot.com/2008_01_01_archive.html

…The Johns approach has been far more influential in American art. Although most Pop and minimal artists of the period opposed the Vietnam War, their work was typically clever and knowing — more a product of the seminar room than of the streets. Golub was an odd man out, one of those who kept alive certain ambitions scuttled by the artists who followed Abstract Expressionism. Golub clung to the figure. He believed he could still make use of great old art, such as classical friezes. He was not ironic. His politics stemmed more from the old left’s cry for social justice than from Foucault’s fashionable dissection of power. He refused to give up the public ambitions of history painting and subside into the merely personal. To put it differently, he would not withdraw art from the suffering of the world. Like Goya, Golub,… could not forget the monsters among us. He was rude, embarrassing, and admirable….

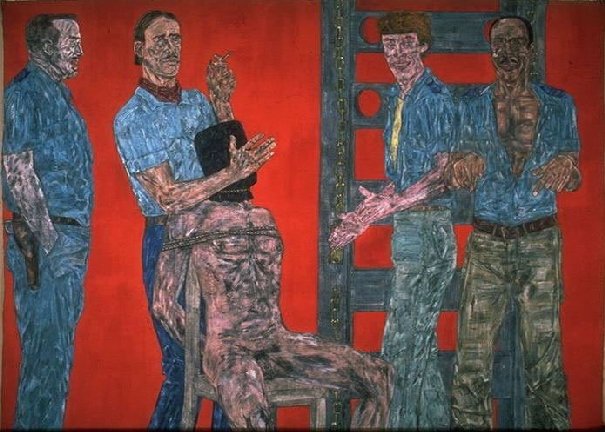

---It is as if we wander around in a peristaltic aura, which shakes with the gray jelly of father and Dagwood as well as of soul and man. Golub's mercs are like worms slithering around in the interstices of our baffling and pathetic self-regard. Their smiles go into our eyes with the same subtle and voracious glee with which they offer their zippered fly-covered hardon to a whore or their boot tip to the forehead of a crawling man.--- Read More:http://www.flashpointmag.com/golub.htm

…Before the Vietnam War, Golub depicted the human monster as a kind of historical abstraction. The primitive figures in his “giantomachy” pictures, in which huge looming forms endlessly beat one another, have a timeless aura. In the napalm paintings, however, the barbarity of the ages suddenly breaks into the present. Golub left the canvas raw and sometimes jaggedly ripped, as if cruelty permitted no time for a more artful presentation. …

---... It is a painting that is also a sculpture. At first, what you see is simple: the stars and stripes, love 'em or hate 'em. Look closer - and this is, profoundly, a work of art to experience in itself. In the original - owned by New York's Museum of Modern Art since the 1950s - you start to see are fragments of headlines and photographs clipped from newspapers, sunk beneath the soft waxen surface of the work. Johns painted Flag using the encaustic method, an ancient art form in which pigments are suspended in hot wax. Mummy portraits from the Fayoum delta use encaustic methods to create astonishingly sharp images of faces. Johns uses it to build a flag that is more solid and more substantial, somehow more real, and yet also more complex and infinitely more enigmatic, than an actual flag. Instead of capturing the waving motion of a banner held aloft - as Uccello does in The Battle of San Romano and as, in an American context, Emmanuel Gottlieb Leutze does in his stirring 1851 history painting Washington Crossing the Delaware - Johns freezes its motion. His flag will never flutter. It is a monument to a flag: the flag mummified. In its stilled lucidity lurk half-readable stories: the small-fry stuff of yesterday's papers, or important events? Do they add up to some secret meaning? There is the sense of many lives, many narratives hidden beneath the common identity of Americans. This painting, this artwork, is like a great American novel. It captures in its monumental ghostly depths the intricate truths every simple facade conceals. Who are Americans? What are they like? The truth lies deeper than the stars and stripes.--- Read More:http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2008/oct/24/jasper-johns-jonathan-jones-flag

…In the next few years, Golub found his essential subject: thuggery. He has made other kinds of pictures, such as portraits and personal meditations upon death, but he will be remembered for his brutes. During the seventies and eighties, Golub regularly made pictures of mercenaries and goons beating, humiliating, and killing their victims; often the victim looks like a piece of human meat. His depiction of the suffering of the powerless arouses pity in the viewer, but it is not the victims themselves who are the focus of Golub’s art. What really gets Golub is the big creeps with loutish leers. No one has better captured the idiot, animal brutality of a certain subset of man. Golub knows how goons stand, how they gloat, how they smoke. He knows what unbuttoning your shirt to the navel can signal and what a beefy forearm can mean. The physical bullying is not just illustrated but presented viscerally through the paint. The roughness of Golub’s surfaces skins the eye. The scrawled lines convey the desperation of a prisoner who uses a nub of chalk to send hopeless messages into the world. It takes a strong but gentle sensibility to expose, with such wounding intimacy, the details of male cruelty — which is why Golub’s art seems, paradoxically, so tender….

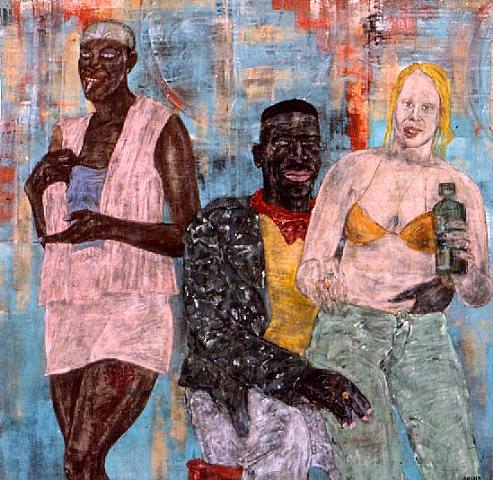

---In his "Horsing Around" paintings, we join the mercenaries at Miller Time. A holstered black man sits with a leering blonde on his knee. They pose happily for our camera (so to speak): She shows us her tongue, he sticks his fingers possessively down the front of her jeans. They're stupid, innocent, murderous, vulnerable, infinitely dangerous, and painted in the vehement colors of one of Gauguin's Tahitian spirits.--- Read More:http://articles.latimes.com/1985-05-26/books/bk-5782_1_leon-golub

…Golub’s goons often seem to look or glance outside the picture, as if they were seeking some sign of approval for their performance. In that way, Golub implicates the larger society — and the viewer — in the crimes being committed. Are we just standing around looking at pictures? Do we have the courage to stop what’s happening backstage? The implication of the audience is one of the best and most disturbing aspects of Golub’s art and goes some way toward offsetting my principal reservation about his art — that despite its heat and immediacy, viewers can too easily distance themselves from the crimes. Judging these thugs presents no problem. They are so awful they almost represent another species. Viewers can even indulge in a kind of self-congratulatory righteousness: I am not that. In the work of Goya, by contrast, no such separation can take place. The monster lives within the human heart. The shadow cannot be shaken….Read More:http://nymag.com/nymetro/arts/art/reviews/4785/

---Another part of me believes that only when I can walk into a Bank of America and confront Interrogation II hanging over the bent heads of the tellers, will Golub's art have been truly received. And I don't expect that to happen in either of our lifetimes. In fact, if it did, a whole set of paranoiac

culations would be set in motion, like: Has North American society now assimilated (co-opted) even Golub? The pessimistic part of me says that seeming acceptance by one's enemies is much more undermining than their rejection. Paradoxically, one needs, is even nourished by, rejection on the part of a society that in its actual daily performance denies the self a sense of worth and imaginative fulfillment.--- Read More:http://www.flashpointmag.com/golub.htm

ADDENDUM:

Golub not only sought to draw attention to the depredations of the US in Vietnam, he focused on militarism and injustice wherever it was to be found. He said of his works, “There was World War II, Korea, Vietnam. How are you going to connect with those fantastic numbers of slaughters? You can’t do it by making pretty pictures about it. You have to create these kinds of stylized forms which are so brutal that they jump beyond the stylization.” Golub’s technique in painting conveyed a sense of violence. He would apply and then scrap off the paint over and over again, until the painting’s surface texture was as disfigured as the war victims he painted.Read More:http://www.art-for-a-change.com/vietnam/vietnam.htm

———————————–

According to Kuspit, Golub was depicting ‘increasingly undisciplined, paramilitary types . Golub found mercenaries, who were usually older than regular soldiers and from more diverse backgrounds, interesting for sociological and psychological reasons. In conversation the artist said he became interested in portraying black mercenaries in relation to white mercenaries and exploring racial hostility, even within the same group. He then wanted to investigate ‘a subtly felt sexual ambivalence – men away from women – or whether there was hostility or attraction. Just to see if it was possible to enter that world, it became very exciting to me to conceive it’ . Unlike the the more generalised heads in the ‘Gigantomachy’ paintings of 1965–7, Golub’s mercenaries are depicted as individuals, like the political portraits he made of world leaders between 1976 and 1979, including Ho Chi Minh, General Pinochet, Nelson Rockefeller and General Franco.

In an interview given in 1988 on the occasion of ‘Committed to Print’, an exhibition of political prints at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Golub said that he believed that prints could have a greater political effect than paintings, because they are cheaper, produced in large numbers and can be widely distributed. The smaller scale of prints make them more manageable and less ‘threatening’ than paintings. He said, ‘even wall-sized prints are not so huge. They’re controllable, visually and environmentally. There’s also a distinction about paper, because it’s fragile, and we discard it. So in a certain way, it’s more intimate’ (Nancy Princenthal, ‘Political Printers: An Opinion Poll’, Print Collector’s Newsletter, vol.19, no.2, May–June 1988, p.45). Read More:http://beta.tate.org.uk/art/work/P77251?text_type=catalogue_entry

COMMENTS

COMMENTS