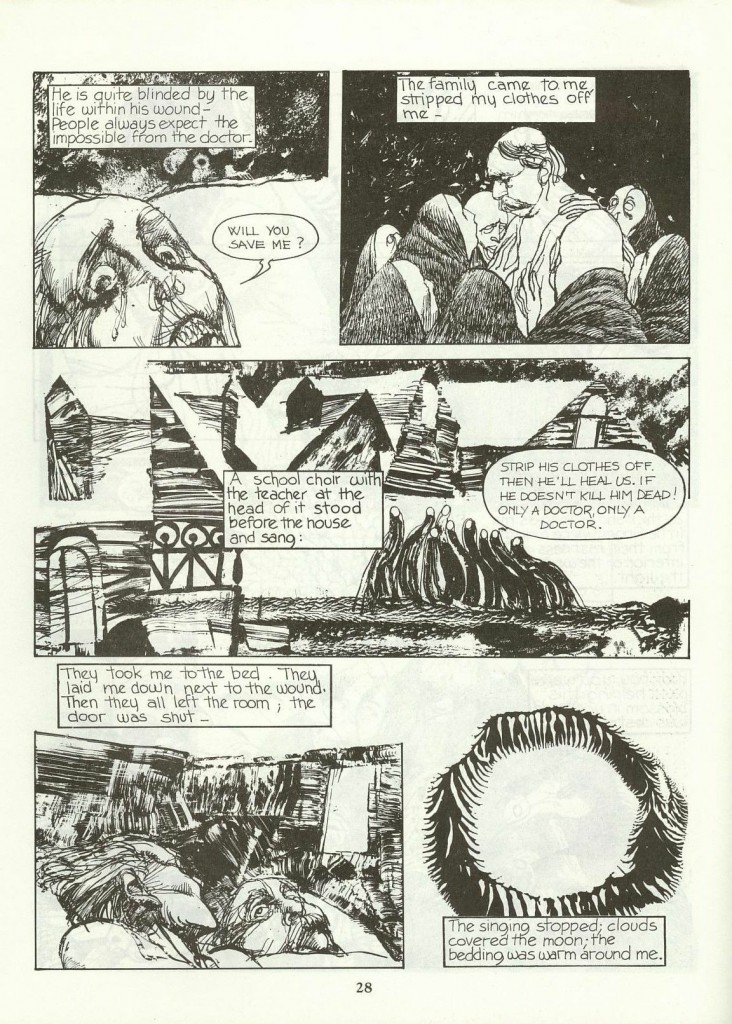

It is another odd Kafka story: A Country Doctor. And the story of another peculiar fellow: Bernard Berenson. The aesthete and art dealer/pundit of late nineteenth-early twentieth century who promoted and profited from selling Italian Renaissance art to the deep pocketed upper crust of American society. Kafka’s story began:

“I was in great perplexity; I had to start on an urgent journey; a seriously ill patient was waiting for me in a village ten miles off; a thick blizzard of snow filled all the wide spaces between him and me; I had a gig, a light gig with big wheels, exactly right for our country roads; muffled in furs, my bag of instruments in my hand, I was in the courtyard all ready for the journey; but there was no horse to be had, no horse.”

Berenson, had a certain calling, a kind of doctor of art, but in taking a set of horses from a mysterious groom in the barn, he made a Faustian pact that allowed the fox ( the groom) into the henhouse ( the maid) with inevitable results, and the doctor traveled to his patient. A rape of Europa, a Sabra and Chatilla scenario. The story ends:

“A false ring of the night bell, once answered — it can never be made right.” Berenson can be looked at a the groom, an outsider, a Jew, who once allowed into the house took it over and made it in his image, profiting from the arrangement, or as the doctor, a kind of wandering Jew domed to travel in a misguided adventure destined from the start to end in eternal damnation and a blaming of others for his own failures. The groom and the doctor are somehow opposites connected to the same desire to escape origins, one completely sublimating his desires the other almost overly open in his erotic pursuits of the maid. The story symbolizes also the failures and successes of emancipation but ultimately a certain doom that normalization whether on a higher, prestigious or more lower strata is not feasible, but almost a rite of passage in internalizing negative images of which nothing redeeming can arise from it.

In the story, you even wonder if the bleeding child is a Christ figure and the Doctor is emblematic of bourgeois guilt, a kind of gnawing doubt that eats away at him; his place in the house taken by the groom who will go through the same cycle ….

Berenson was an art doctor, attending to patients needing art; he collected an incredible 25% on the sale of painting profits, and with Joseph Duveen had a monopoly on Italian Renaissance art the way De Beers had a grip on the diamond industry. Berenson also made money on consulting fees, authentication, and providing certificates while not revealing his role as salesman to the client; the tendency was to inflate values and take banal generic paintings of the period,”ready-mades” spruce them up , like putting lipstick on a pig, and pawn them off as important works. Maybe to be expected; he was born on a shetl, real name Bernhard Valvrojenski, child of a poor lumber merchant who had a certain antipathy of traditional Judaism.

This was always the bind of a Berenson or a country doctor. By the 1900s the formal emancipation of German Jews, first begun by Napoleon in France, was complete and they had achieved a very high degree of assimilation. But the paradox was that like Berenson, who actually had himself baptized, which reminds me of Max Jacob- maybe as an antibiotic to his sublimated gayness?- the more they demonstrated their desire to be the same as everyone else, they more they were reminded of their otherness. The more they distanced themselves from their Jewish identity the further away seemed the prize of complete acceptance. The more Berenson wanted to be accepted as a scholar, the more he engaged as a kind of art trader, a peddler like his father except of more lucrative and exotic materials. But the same cap in hand slap at his own feelings of self worth.

Zoffany. Read More:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Tribuna_of_the_Uffizi_%281772-78%29;_Zoffany,_Johann.jpg

The response, like many before and after Berenson, and intended to help overcome those barriers, was to find fault in whole or in part, at the feet of Jews themselves, to see weaknesses in Judaism, Jewish culture, Jewish mannerisms, Jewish ways of responding, Jewish culture, social culture while ignoring Torah culture; the cultivation of group inferiority. It was suggestive of the tendency to internalize less than flattering t images soc

imposed on them, a “society” that was in some measure more assimilated; stemming from the increase in public Anti-Semitism, they sought to appease their persecutors in order to inculcate a bit of traction on the acceptance front; in the case of Berenson almost pathologically reduced to a dandyist ideal of life lived as a procession of exquisite moments shaped by aesthetic considerations….

---In his book, Trials of the Diaspora, Julius calls them “scourges,” a term I prefer because it relates to their self-anointed role as prophets, whipping the wayward Jewish people into line. The Temptation of Innocence Ruth Wisse, in her book Jews and Power, identified the tendency of some Jews to vociferously oppose their own community as a dynamic which she, in part, attributes to a Jewish uneasiness with the projection political power and a tendency to almost fetishize the Jews’ history of powerlessness. Wisse concludes that Jews who endured, or know the history of, the powerlessness of exile are in danger of mistaking it for a requirement of Jewish life or, worse, for a Jewish ideal. This puerile desire not to be corrupted by the complexities, and occasional compromises, necessitated by possessing moral agency is described by Pascal Bruckner as “The Temptation of Innocence.”--- Read More:http://www.theaugeanstables.com/2010/08/11/not-self-hating-jews-but-jewish-scourges-of-jews/ image:http://miedomonstruocine.blogspot.ca/2011/04/bernard-berenson-vivir-la-obra-de-arte.html

( see link at end) ….he remade himself. The pallid, bookish Litvak became, as Secrest puts it, “the very model of a proper Bostonian, circa 1885: polished, impeccably mannered, exquisitely educated, and fastidiously aesthetical.” In the process, he had to submit to the judgments of his social superiors, most of whom were quietly anti-Semitic. Berenson missed the high tide of proper Bostonian Jew-hating, which came after the great exodus of Jews to America in the late 1880s. Nevertheless the prejudices he met in the society he aspired to join were of an almost Prussian nastiness, and they skewed his life….

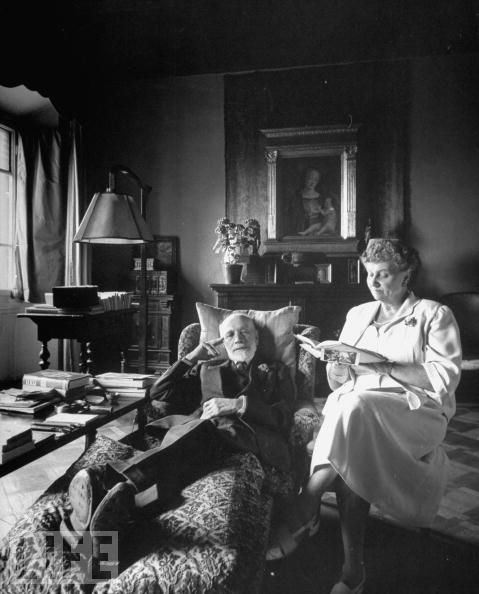

Bernard Berenson. ---The reinvention of the Renaissance by Burckhardt and his followers had an immense effect on American cultural life in the 1880s, and when the millionaires and their wives began to identify with the condottieri and doges to the point of wanting to own the art they had commissioned four centuries earlier, Berenson’s fortune would be made. --- Read More:http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1979/dec/20/only-in-america/?pagination=false image:http://life.time.com/

He set out to cover his traces. Berenson had an almost pathological need to dissemble his own Jewishness, and Secrest quotes a remarkable passage from an essay that he sent to the Andover Review when he was twenty-three:

It is only by a study of Jewish institutions and literature that we shall begin to understand the puzzling character of the Jews. Begin to understand, I say, for comprehend them we never shall. Their character and interests are too vitally opposed to our own to permit the existence of that intelligent sympathy between us and them which is necessary for comprehension….

This drive to become a Gentile at almost any cost was the fruit of real desperation: young Berenson experienced his race and origins as a Medusa’s head which could petrify his career at one glance. His social climbing, which looks so repellent and calculated, was inspired by the conviction that there was no way back. Proper Boston possessed the first culture he wanted to have; Jewishness was not a culture, only a point of origin, something to transcend by means of any available fiction. In his old age, Berenson would make peace with his childhood, becoming almost rabbinical. But for the first fifty years of his life he fought to overcome and repress it, so that the gifted shtetl boy was displaced by a more literary specter—the pale exile of conjectural but high origins, bestowing his allegiance only on Culture: a Childe Harold of the salons and museums. His pedigree could not impress Boston, but his credentials of feeling could. Read More:http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1979/dec/20/only-in-america/?pagination=false

…One ingredient of this future ruckus was their utter indifference to conflict of interest; it was Mary’s regular practice, from 1894 onward, to publish glowing notices of Bernard’s work wherever she could place a review, sometimes under her own name, sometimes under assumed ones.

But what Berenson most needed was an opportunity to carry out a public slaughter of established attributions. He got it in 1894, with an exhibition of Venetian painting from British collections at the New Gallery in London. When Berenson’s essay on this show appeared, it transformed him at once into an enfant terrible. Of thirty-three works attributed to Titian in English collections, for instance, he spared only one, the Mond Madonna, assigning the rest to copyists or to such minor figures as Polidoro Lanzani, Santacroce, and Beccaruzzi; of seven “Mantegnas” he accepted two; and so on.

Since nearly all the paintings in the show were owned by rich and titled Englishmen, Berenson’s pamphlet stirred up the art establishment. It achieved its end, since if all earlier Renaissance attributions, in England as in Italy, could have doubt cast on them, whom could collectors trust? None but Berenson himself, the new authority. And so, amid envy from other critics and rancorous hostility from dealers whose swans he was degrading to ducks, Berenson—still the picture of scholarly detachment, the young aufklärer with no visible allegiances to any established art world interests—quite rapidly became what he would remain for another fifty years: the filter through which most Renaissance art, entering the new-money collections of the New World, had to pass.

The critic who deals is a common spectacle, and not a noble one; the only way to keep your nose clean in the art world is not to collect at all, and very few writers are prepared to do that. In Berenson’s time it was simply assumed that art critics and art historians were up for sale and on the take, unless they were so rich as not to need the money….Read More:http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1979/dec/20/only-in-america/?pagination=false

…Since few American collectors were prepared to buy an Italian gold-ground predella fragment, let alone a full-dress portrait by Titian or Moroni, without a Berenson ticket on it, the volume of his business was immense. It is impossible to say, without access to the Berenson-Duveen correspondence, how many works of art (if any) Berenson upgraded to enhance their market value, but Secrest appends to the end of her text a long and interesting list of Berenson attributions that have gone down since his death, or jumped from school pieces to autographed works when they were in Duveen’s hands. A spectacular case of this was a “Masaccio” acquired from Duveen by Andrew Mellon, the Madonna of Humility, a wreck with only a few square inches of genuine paint left on it. Berenson went so far as to publish it while it was still in Duveen’s hands, writing that no painting of equal splendor had been seen “since the builders of the Pyramids and the sculptors of the Chefrens….” It is now in storage in Washington. … ( ibid.)

ADDENDUM:

Hugely influential in this rebirth was Kurt Lewin, until 1932 professor of psychology at the University of Berlin. He emigrated from Germany in 1933 after Hitler had come to power. In 1941 he wrote an essay, ‘Self-hatred among Jews’, published in an American Jewish Committee-sponsored journal, which was much cited and frequently quoted. Lewin was the leading exponent of the study of group dynamics in the United States and a highly regarded social psychologist. He reinterpreted the problem as one mostly affecting the group rather than the individual. Not surprisingly, given the threat to Jews at the time, and his view of the failure of German Jewish leaders to give public support to Jewish institutions, he argued that criticism of the group weakens and endangers it, and those responsible for that criticism are unable to adjust to the group’s problems. The result is ‘neurosis’ manifesting itself as self-hatred. Read More:http://www.jewishquarterly.org/issuearchive/article2366.html?articleid=432

——————————-

“Shall I hitch up?” he asked, crawling out on all fours. I didn’t know what to say and merely bent down to see what was still in the stall. The servant girl stood beside me. “One doesn’t know the sorts of things one has stored in one’s own house,” she said, and we both laughed. “Hey, Brother, hey Sister,” the groom cried out, and two horses, powerful animals with strong flanks, shoved their way one behind the other, legs close to the bodies, lowering their well-formed heads like camels, and getting through the door space, which they completely filled, only through the powerful movements of their rumps. But right away they stood up straight, long legged, with thick steaming bodies. “Help him,” I said, and the girl obediently hurried to hand the wagon harness to the groom. But as soon as she was beside him, the groom puts his arms around her and pushes his face against hers. She screams out and runs over to me. On the girl’s cheek are red marks from two rows of teeth. “You brute,” I cry out in fury, “do you want the whip?” But I immediately remember that he is a stranger, that I don’t know where he comes from, and that he’s helping me out of his own free will, when everyone else is refusing to. As if he knows what I am thinking, he takes no offence at my threat, but turns around to me once more, still busy with the horses. Then he says, “Climb in,” and, in fact, everything is ready. I notice that I have never before traveled with such a beautiful team of horses, and I climb in happily. “But I’ll take the reins. You don’t know the way,” I say. “Of course,” he says; “I’m not going with you. I’m staying with Rosa.” “No,” screams Rosa and runs into the house, with an accurate premonition of the inevitability of her fate. I hear the door chain rattling as she sets it in place. I hear the lock click. I see how in addition she chases down the corridor and through the rooms putting out all the lights in order to make herself impossible to find. “You’re coming with me,” I say to the groom, “or I’ll give up the journey, no matter how urgent it is. It’s not my intention to give you the girl as the price of the trip.” “Giddy up,” he says and claps his hands. The carriage is torn away, like a piece of wood in a current. Read More:http://records.viu.ca/~johnstoi/kafka/countrydoctor.htm

COMMENTS

COMMENTS