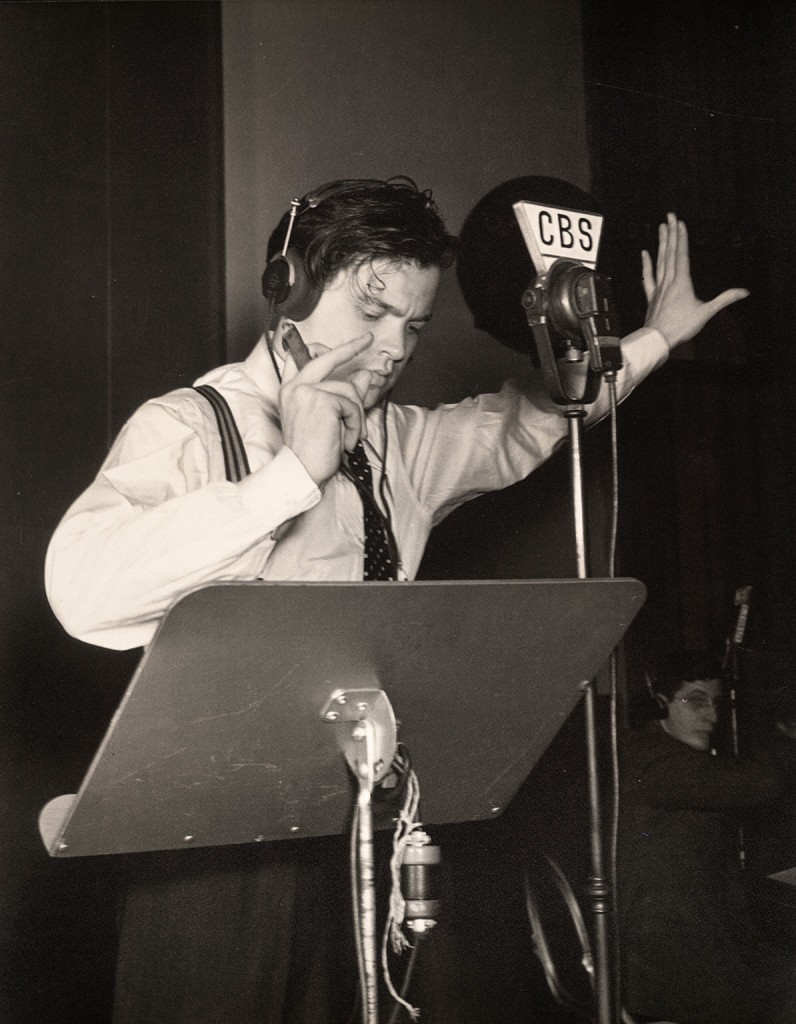

Orson Welles. The prodigy. It is only rarely that the child prodigy converts into an adult prodigy, in fact statistically not very promising, but Welles pierced the prodigal ordeal of circumstances into an association with real achievement. The crowning of the adult radio maestro was War of the Worlds, an ingenious put-on that became a classic example of mass hysteria, and how the media could be complicit. Hadley Cantril posited the theory soon after, that social panics of this nature could be systematically stimulated, Nazi Germany was proof, when large, target audiences were unable to discern reliable from unreliable sources of information. Effectively Welles was playing on some of the same themes being elaborated by Edgar Bernays and Walter Lippman, and the manipulation of trauma…

…We now come to 8 P.M. on the evening of October 30, 1938, Halloween, when The Mercury Theatre of the Air, directed by and starring Orson Welles, was to give its regular weekly entertainment in the series called “First Person Singular.” The idea was to adapt famous stories- Jane Eyre, Treasure Island, Oliver Twist, The 39 Steps, were some that had been used- to a formula particularly suitable to radio. As Welles explained it once, “When someone comes on the air and says this happend to me, you’ve got to listen.” They certainly listened to the offering of October 30th, The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells.

---From there the Martians began decimating the denizens of New York with heat rays and poisonous black smoke. Please hold your snide remarks. Think people of that bygone era were gullible? Don’t forget with war on the horizon in Europe, fears of invasion and mass destruction were keeping those folks up at night. War of the Worlds played on those apprehensions with gleeful abandon.---Read More:http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/aroundthemall/2008/10/fake-radio-war-stirs-terror-through-us-orson-welles-war-of-the-worlds-turns-70-2/

The narrative method used on this particular evening was as simple as it proved devastating. Welles created a false newscast. He updated the original story to the night in question and set its critical episode in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, a remote town that was yet not far from New York, and within easy reach of a very large segment of the listening audience.After the customary station introduction and a brief “foreward” by Welles, both of which made it crystal clear that this was fiction and both of which were as clearly missed by millions of late tuners, the “show” started with a weather forecast , followed by dance music from the Hotel Park Plaza, a fictional hotel, in New York.

There came shortly an interruption: Intercontinental Radio News, also fictional, had just issued a bulletin about several large explosions on Mars that had been detected on the earth a half-hour earlier. Then more music, then additional explosion details, followed by a “background” interview with Professor Pierson ( Welles) of the Princeton observatory. This was in turn interrupted by a flash: “a huge flaming object” had fallen in a farmer’s field near Grovers Mill.

No one should have been fooled. There was the standard station opening, there was a mid-hour identification, and no other station on the air was “reacting” to the ghastly events. Further, the events took place at ludicrous speeds. For example , Dr. Pierson would have had to drive from Princeton to Grovers Mills over the back roads of New Jersey at several hundred miles per hour to arrive at the moment he was heard to say, ” the metal casing is definitely extraterrestrial.” Finally, one would have thought that a “meteor”with a screw top was a sufficiently tripe hobgoblin to disabuse the most gullible. One would have thought wrong.

America, or a significant segment of America, panicked as Welles spun the old Martian thriller out over the CBS network. The worst disorders occurred in New Jersey, near the place where “the monsters had landed.” Highways were blocked with refugees fleeing the lethal gas of the invading octopi; the telephone system broke down, police stations were jammed, and at least one of them advised hysterical questioners to follow precisely the advice coming from their radios. It all lasted only an hour or so, but the anguish induced across the whole country is entirely incalculable.

The yarn was so shopworn, Welles had hesitated to use it, and the reasons for the response with the show serving as pretext, or trigger for other forces is apparent; but in defense of the common sense of the American public, such as it is, it should be recalled that the capitulation of Chamberlain at Munich had occurred only a month earlier, and terror was epidemic in the world.

The relevant point is that, as a prodigy, Welles was lucky again. He hadn’t meant to cause suffering with his Halloween charade; he hadn’t schemed to become a national focus of mixed admiration and anger. Nevertheless, events had shown in the most dramatic way co

vable that the touch of Orson Welles was unlike the touch of other men.ADDENDUM:

( see link at end) ….Ladies and gentlemen, this is the most terrifying thing I have ever witnessed…Someone’s crawling out of the hollow top…The whole field’s caught fire…It’s coming this way. About twenty yards to my right—”

Silence. Dead silence. This is bad. What’s going on? Have Martians invaded Earth? Can’t be, right? But it’s on the radio, and the radio doesn’t lie. Is that smoke I smell? Why is old lady Johnson screaming next door? Holy hell…

Similar scenes were repeated all over the East Coast. Listeners poured into the streets. Some headed to church. Others headed to spend their last hours on Earth with family. Wet towels served as makeshift gas masks to protect against the poison gas the radio said was headed outward from New Jersey. Many were convinced it was the end of the world.

When producer John Houseman suggested The War of the Worlds as the Mercury Theater’s Halloween eve broadcast, director and star Orson Welles laughed it off as silly and dull. Eventually, the idea surfaced to update the 1898 H.G. Wells story and split it into two. The first part would take the form of a series of musical pieces broken up by increasingly urgent news bulletins. No radio play before had toyed with the form like this, and the bulletins — at this point old hat to Americans familiar with the dire updates coming out of Europe — gave the story a sense of verisimilitude that it otherwise would have lacked.

Read more: http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1855120,00.html#ixzz1wAcOqs00

———————

The aftermath: Orson Welles “The War of the Worlds” Halloween press conference, 1938

There are pictures of me made about three hours after the broadcast looking as much as I could like an early Christian saint. As if I didn’t know what I was doing… but I’m afraid it was about as hypocritical as anyone could possibly get!

—Orson Welles (to Tom Snyder – 1975) Read More:http://www.wellesnet.com/?p=296

COMMENTS

COMMENTS