The travels of Ibn Battuta. The diaries of the Wayfarer, Batuta in sum, laid out the compelling argument that Islam was more than an empire, more even than a faith, or an ideology. All apsects of human conduct were governed by its precepts. It was a religion, a style, a code of conduct, a loyalty, a system of law, a literature, a language, It was as though the Roman law, the Catholic faith, and the social nuances of the British Empire were all combined in one all-embracing system. The wandering Muslim could expect more especially if he was a learned man of religion. It was like an immense freemasonry, expressed not only in human relationships and legal practice but in the grand mosques of the Islamic architecture, in the caravansaries of the pilgrim routes, in the common treasury of Arab legend and tradition, in the music of the Arabic tongue, and in the shared conviction that there was one god and Mohammed was his prophet.

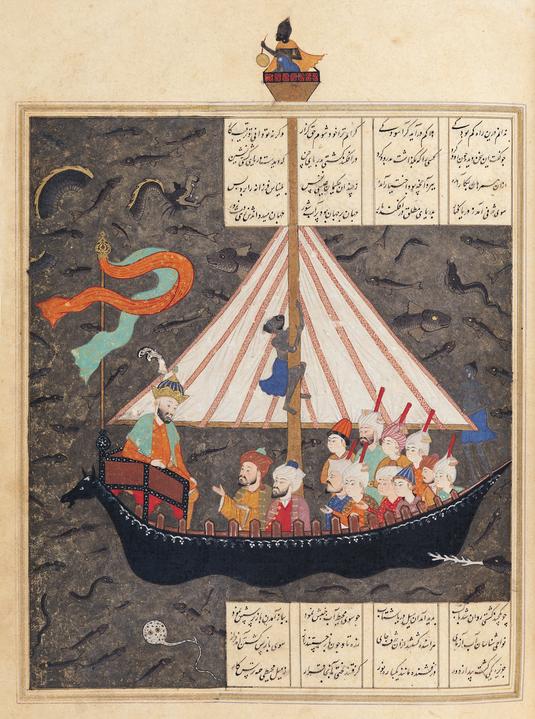

---A boat in the Persian Gulf with on board Abou Zayd, arab miniature by Al Wasiti from "Maqamat" by Al Hariri, 13th century Caption: UNSPECIFIED - MAY 04: A boat in the Persian Gulf with on board Abou Zayd, arab miniature by Al Wasiti from 'Maqamat' by Al Hariri, 13th century (Photo by Apic/Getty Images)---Read More:http://www.gettyimages.ie/detail/news-photo/boat-in-the-persian-gulf-with-on-board-abou-zayd-arab-news-photo/89864180

No wonder a Moslem was proud of his faith. The empire of Islam might be disintegrating, but the idea of Islam was as powerful as ever, and every Moslem felt himself inherently privileged. Islamic potentates bore themselves with immense splendor and confidence. Islamic soldiers certainly assumed Alah to be on their side, after all, they had expelled the Christian crusaders from the holy places of Palestine. The crescent of Islam was not only a holy talisman, but a sign of brotherhood too, and a reminder of common triumphs and aspirations. So the world of the Moslems , hard though it was to define politically, did constitute a civilization.

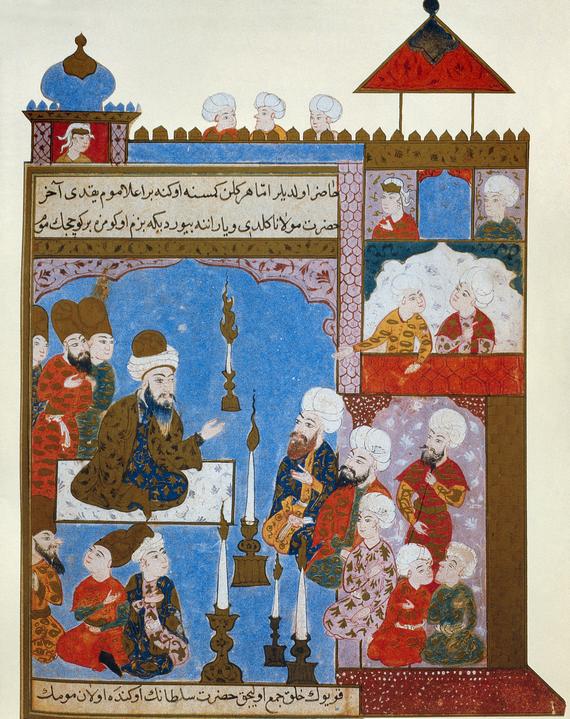

army of suleyman the magnificent. Read More:http://www.artfinder.com/user/6856/collection/indian-persian-miniatures/?_view=two&page=31

It was into this diverse and politically decadent society that the young Ibn Battuta set off upon his travels in 1325. His first destination was the classic objective of Islam, Mecca itself, but before he laid down his staff at last in Abu Inan’s capital of Fez, he saw sights no Moslem had ever seen before or for that matter, would ever be seen again.

He traveled for three decades, sometimes staying put for years at a time, sometimes beginning a new journey almost the moment he finished the last. Hit itinerary was wayward. He made the pilgrimage to the Hejaz six times, and he went to India specifically to seek employment in the service of the powerful and ferocious Sultan Mohammed Tughlak. Otherwise, he simply wandered impulsively: when the spirit moved him, when somebody offered him safe conduct, when a junk sailed unexpectedly, when he took a fancy to see a strange country or interview some celebrated ascetic.

Rumi. Candle still lit. Read More:http://www.artfinder.com/user/6856/collection/indian-persian-miniatures/?_view=two&page=30

Early in his traveling life he resolved that he would never follow the same route twice, and a map of his journeys looks like the route of some aimless vagrant, all loops and backtracks, sudden forays and purposeless detours. For thirty years his relatives and friends in Morocco could never be sure where he was, and along the way he picked up and discarded wives and slaves with easy abandon. Fitfully, news of him passed along the Islamic grapevine, from Ceylon to India, to Niger; in lands to the east they called him God’s Sun, for he did seem to move in some inscrutable, diurnal motion, now shining with success, now dimmed by disfavor. During those thirty years of travel he covered the entire Islamic world from North Africa to Turkey, Yemen to Aden, The Crimea, the Caucasus, India and China, the last in which he lost all of his possessions , acquired four wives, and became “quadi” of the Maldive Islands.

---The voyage of Alexander the Great. Read More:htt

www.artfinder.com/user/6856/collection/indian-persian-miniatures/?_view=two&page=29

He retired to Fez at last in 1354, spending the rest of his life remembering it all, and died in 1378 when he was seventy-three.

ADDENDUM:

( see link at end) …The story of a slave who broke a valuable dish

Besides these there are endowments for other charitable purposes. One day as I went along a lane in Damascus I saw a small slave who had dropped a Chinese porcelain dish, which was broken to bits. A number of people collected round him and one of them said to him, “Gather up the pieces and take them to the custodian of the endowments for utensils.” He did so, and the man went with him to the custodian, where the slave showed the broken pieces and received a sum sufficient to buy a similar dish. This is an excellent institution, for the master of the slave would undoubtedlv have beaten him, or at least scolded him, for breaking the dish, and the slave would have been heartbroken and upset at the accident. This benefaction is indeed a mender of hearts–may God richly reward him whose zeal for good works rose to such heights!

The hospitality and friendship received by Ibn Battuta

The people of Damascus vie with one another in building mosques, religious houses, colleges and mausoleums. They have a high opinion of the North Africans, and freely entrust them with the care of their moneys, wives, and children. All strangers amongst them [i.e., among North Africans like Ibn Battuta] are handsomely treated and care is taken that they are not forced to any action that might injure their self-respect.

When I came to Damascus a firm friendship sprang up between the Malikite professor Nur ad-Din Sakhawi and me, and he besought me to breakfast at his house during the nights of Ramadan. After I had visited him for four nights I had a stroke of fever and absented myself. He sent in search of me, and although I pleaded my illness in excuse he refused to accept it. I went back to his house and spent the night there, and when I desired to take my leave the next morning he would not hear of it, but said to me “Consider my house as your own or as your father’s or brother’s.” He then had a doctor sent for, and gave orders that all the medicines and dishes that the doctor prescribed were to be made for me in his house. I stayed thus with him until the Fast-breaking when I went to the festival prayers and God healed me of what had befallen me. Meanwhile, all the money I had for my expenses was exhausted. Nur ad-Din, learning this, hired camels for me and gave me travelling and other provisions, and money in addition, saying “It will come in for any serious matter that may land you in difficulties”–may God reward him ! …

…The pious kindness of the people of Mecca

The inhabitants of Mecca are distinguished by many excellent and noble activities and qualities, by their beneficence to the humble and weak, and by their kindness to strangers. When any of them makes a feast, he begins by giving food to the religious devotees who are poor and without resources, inviting them first with kindness and delicacy. The majority of these unfortunates are to be found by the public bakehouses, and when anyone has his bread baked and takes it away to his house, they follow him and he gives each one of them some share of it, sending away none disappointed. Even if he has but a single loaf, he gives away a third or a half of it, cheerfully and without any grudgingness.

Another good habit of theirs is this. The orphan children sit in the bazaar, each with two baskets, one large and one small. When one of the townspeople comes to the bazaar and buys cereals, meat and vegetables, he hands them to one of these boys, who puts the cereals in one basket and the meat and vegetables in the other and takes them to the man’s house, so that his meal may be prepared. Meanwhile the man goes about his devotions and his business. There is no instance of any of the boys having ever abused their trust in this matter, and they are given a fixed fee of a few coppers. Read More:http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1354-ibnbattuta.asp

COMMENTS

COMMENTS