“Sleep is lovely, deaht is better still, not to have been born is of course the miracle.” Heinrich Heine

…Samuel Beckett and the celebration of the nausea of existence, which often has little to do with despair. In Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape, the hero has been trapped in a cage for thirty years, but its doubtful that even the least sensitive memeber viewing this would care to put their arm through the bars. Krapp has the stare of a badger. Despair has not tamed it. It is curious about Beckett that, though he deals in the most dire experience, his fables do not depress. There is a salty virility to his people, an assumption of equaklity with juggernaut, that gives off the exciting smell of human pride. “Use your head,” says Hamm in Beckett’s play Endgame, “use your head, can’t you, you’re on earth, there’s no cure for that!” No more is there, but it does not occur to a Beckett character to take that grim fact lying down.

—The great British actor John Hurt begins his achingly fine performance of “Krapp’s Last Tape” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Harvey Theater with wordless moments that seem to stretch into eternity. With his hands gently placed on a worn desk, he peers out at the audience with an expression intimating that his craggy, disheveled character sees no reason to communicate anything at all. As the seconds tick past, and Mr. Hurt keeps on staring, and stares some more, we become uncomfortably aware of the heavy tread of time as it plods by.

This is entirely apt, because time, in all its ornery complexity, fleeting and ponderous, slipping through the fingers even as it weighs upon the soul, is a central theme in Beckett’s 1958 one-act. —Read More:http://theater.nytimes.com/2011/12/09/theater/reviews/krapps-last-tape-with-john-hurt-at-bam-review.html

Figuratively speaking, that is. His heroes are not nfrequently lying down when we meet them. Prone or supine- Beckett’s people give a good deal of thought to the relative advantages of the two positions. Supine, one enjoys a breadth of vision, but prone, one can get over the ground more readily, gripping with the knees and digging forward with the fingernails. Proceeding that way, you may advance a good twenty yeards in a day, and who’s to say that a man should reasonably aspire to more. The hub of Beckett’s insight- the recurring vision in the novels like Malone Dies , Molloy and The Unnamable, is that experience is subjective, inviolable, and immeasurable.

Molloy, finding himself on the beach, gathers a little trove of sixteen stones, admirable for sucking, and works out a procedure for enjoying them in orderly rotation. Is this an achievement of less stature than Newton’s formulation of the laws of motion? Well, that would depend on whetehr you put your question to Newton or Molloy. Or do you say that society will judge such matters? I refrain from telling you what Molloy would say if you came at him with a word like “society.”

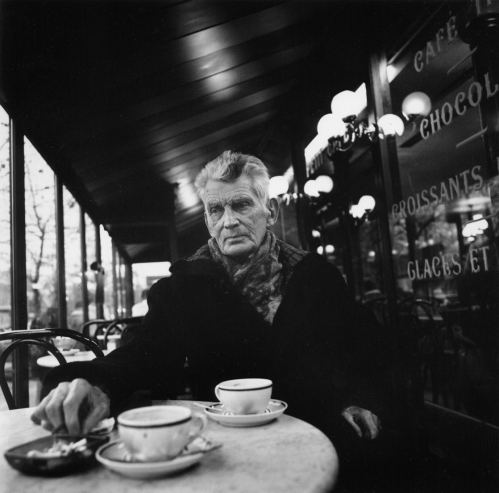

Samuel Beckett. —The Beckett Trilogy is a three–hour tour de force performance of Samuel Beckett’s opus trio of novels: Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable. In their stage version, Conor Lovett and Judy Hegarty Lovett have captured the essence of Beckett’s voice. Molloy, a crippled tramp and one of Beckett’s most poignant and arresting figures, recounts the hilarious attempt to visit his mother. Malone, who is about to die, tries to while away his days by telling aimless stories only to finally lose himself in a whirlwind tale. In the final chapter, The Unnamable, Beckett dispenses altogether with story, or so it would seem. Here, Beckett’s vision finds its most honest, brutal, and beautiful realization as the unnamed narrator struggles with his own existence and the stark awareness that a story cannot help him to understand it any better.

Read More:http://www.pica.org/festival_detail_new.aspx?eventid=605 image:http://thebsreport.wordpress.com/2009/04/13/todays-birthdays-april-13th/

Or consider Malone, also representing the human race. He is almost dead when we first encounter him,and at the end, there is just the difference that he is quite dead. He lies on a bed, he knows not where; brought to this pass, he knows not how; fed by anonymous hands that come no more. He has possessions- one yellow shoe, a hat with the brim gone, a photograph of a donkey with downcast eyes, a needle embedded in two corks, a scrap of newspaper, a stone- and these he can reach and stir with a long stick, for he enjoys the use of his arms. In bed with him are two pencils, one of which he can no longer find, and a notebook. That is important to him, for in the time left to him Malone will tell stories- write them, rather, because the “others do not endure, but vanish into thin air,” The he will make an inventory of his possessions and then he will die.

It cannot possibly be said whether we are with him for twenty minutes or ten years. What is sure is that the acquaintance is amusing ad enriching. That virtual corpse, abandoned on a bed of casters, is an adventurer and commander to shadow Alexander. This is not to traffic in paradoxes; Malone is man stripped to artist. We are the only animal hat sings its own saga, and which is more important the singing or the doing? It is immaterial in Malone’s case, foe he “does” in order to sing. He grasps life because it gives him a story to tell, and when it is done, he is done. Malone, infinitely vulnerable and infinitely tough: “This club is mine. …It is stained with blood, but insufficiently, insufficiently. I have defended myself, ill, but I have defended myself.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS